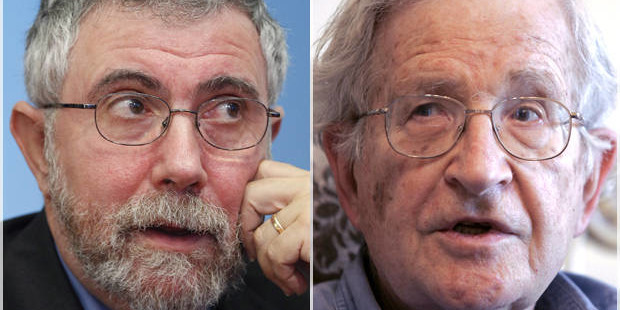

It’s Paul Krugman vs. Noam Chomsky: This is the history we need to understand Paris, ISIS

Krugman mocks idea that US imperialism’s at root of all evil. But scars of our meddling are key to the Middle East

Two remarks a few days apart lead straight to the question posed in this space after last Friday’s tragic events in Paris. Why? Why does the Islamic State wage war? Why does this war now reach into a Western capital? The question is why, the argument being we will get nowhere in resolving a crisis that can no longer be described as the Middle East’s alone until we ask it and attempt answers.

“If you have a handful of people who don’t mind dying, they can kill a lot of people,” President Obama asserted after a Group of 20 summit in Turkey Monday. “That’s one of the challenges of terrorism…. It is the ideology they carry with them and their willingness to die.” The White House transcript of the president’s presser is here.

Interesting in itself. Already we start to answer the “why” question. There is an ideology at work. What is the ideology, then? It arises from exactly what?

The president’s remark is even more provoking of thought when considered next to something Dexter Filkins said on Charlie Rose Friday evening, just as news of the Paris catastrophe was coming in. (Our Charles grows slothful: The program was taped and he should have spiked it. The video recording is here.)

Filkins, once of the Times, now of the New Yorker and throughout corresponding from the Middle East, spoke without reference to the Islamic State’s assault on the French capital, which came over a little bizarrely. Rose had asked him to explain why Iraq remained a shattered polity since the Bush II invasion in 2003 and why it does not effectively resist the Islamic State’s onslaughts.

“Who wants to die for Iraq?” Filkins asked by way of making his point, which was that nobody wants to die for Iraq. Maybe Filkins would agree that there is half an argument for quotation marks at this point: Are we talking about “Iraq,” an idea of a nation more than a nation?

So far, this: Those in the Islamic State will die for their ideology, which is nothing if not of their own making. But few of the 33 million people known as Iraqis seem willing to die for either “Iraq” or Iraq, which the British declared a mandate in 1921, after the French gave up claims to northern provinces awarded in the Sykes-Picot Agreement, signed in secret five years earlier.

Buried not too far below the surface there is a question of identity, isn’t there? I would not want to explain the crisis now emanating from the Middle East by way of a single word, but if I were forced to choose one, this would be it. Among many other things, it is about identity. And we can usefully leave behind the question of who is willing or unwilling to die for what. It is much more productive to think about what the Islamic State’s combatants, or those of any other extremist group, or ordinary, peaceable Iraqis or Syrians want to live for.

It is astonishing to discover how resistant so many of us are to this line of inquiry. More than one reader of last Sunday’s column accuses me of being an Islamic State sympathizer for urging that we consider causality, putting what is undeniably an emergency in an historical context. The grossly pernicious Richard Perle’s “decontextualization” argument, outlined in the column, proves durable and extravagantly destructive—a serious impediment in our quest for a resolution.

The task is to de-decontextualize, if you like wads instead of words. It is not enough to say those turning Syria and parts of Iraq into killing fields are extremists or terrorists or any other term we use to cancel all further consideration of them. It does not matter who is doing what anywhere: Stick figures walk around only in cartoons. There is no such thing as a human being of fewer than three dimensions. Name someone who has no aspirations, however twisted these may be.

In his Monday column in the New York Times, Paul Krugman wrote something very far beneath him. “There are indeed some people determined to believe that Western imperialism is the root of all evil,” he asserted, “and all would be well if we stopped meddling.” I am surprised to see Krugman indulge in this kind of flaccid logic. You can read the column here.

Let me straighten out a few things, given Krugman’s argument is also prevalent. I do not know anyone who “believes” Western imperialism to be “the root of all evil” in the way of a 17th century Puritan preacher. That phrase is straw-man trickery. I know plenty of people who think the scars of Western colonialism, including America’s neo-variety, are key to understanding the Islamic State crisis. They think this because they have resort to history, wherein the Western powers’ responsibility over a long period of time is perfectly plain. To finish the thought, all would be a truckload better if we stopped meddling—this one can stand by without qualification.

*

The question of West’s responsibility in the Middle East’s unraveling is complex—and, for reasons I cannot honestly fathom, controversial. On the very face of it, the Islamic State arose in consequence of the 2003 invasion and the precipitously stupid decision to disband the Iraqi army. Still more immediately, the CIA has cultivated at least some of the terror groups now active in Syria. Who can say how many or which ones? It is not even clear the agency knows the ACs from the DCs in the putrid stew of anti-Damascus militias now on the boil.

Nothing too complicated there. To stay with Krugman’s term, we have been watching real-time meddling, all day every day, for a dozen years in the case of Iraq.

Further back in history, we might start with the prolonged period of decline the Islamic world entered upon beginning in the 16th or 17th century, depending on how one counts. There were many reasons for this—political and economic, primarily—but, crunching down a lot of history, Western intrusion cannot (yet) be cast as a primary cause. What persists from this period, at least among some, is a nostalgia for the greatness of golden age of the caliphates (thought to have begun in the 8th century) and all their scientific, intellectual and cultural achievements.

A condition of decline saw Islamic-majority nations into the 19th and 20th centuries, and here the part played by the European powers becomes more obvious. It was during the 19th century that the West’s modern-day meddling commenced in earnest, chiefly in pursuit of resources. In the century just ended, this came to retarding the political and social impulses to modernize that grew ever more evident throughout the developing world. To most of the world, I should add, to modernize does not equate with Westernizing.

To make the point clear, despotic monarchies may have been historical realities across the Middle East, but the West’s fondness for them—still much with us, of course—was decisive as the last century unrolled and the postwar “independence era” came and went. Exhausted after World War II, Britain and France had passed the ball to the U.S. by the mid-1950s, and Washington has run with it ever since.

This is not a scholar’s account. With complete humility I stand open to the most sweeping correction. But the above serves by way of a broad outline, it seems to me. My point is that we must, must, must begin thinking historically if we are to come to grips with the twin questions of causality and responsibility in modern Middle Eastern history. Only then will we recognize what it is we must do as the history we make grows ever grimmer.

Root of all evil? Who ever said so? Can we keep the conversation serious, please? An accomplice in the past, a perpetrator later on? Who could possibly argue otherwise, providing there is a history book in the house?

I wrote above that I fail to understand why the question of responsibility is controversial. I take it back: This is why. Facing one’s part in others’ deprivation, repression, violence and all the rest is an errand requiring humility, resolve, commitment, and an enlarged vision. We Americans score poorly on all counts these days. But summoning all four—if it helps to think of it this way—is a matter of self-interest now.