“The China choice.”

Between reason and paranoia.

News arrived yesterday that the U.S. Navy dispatched a guided-missile destroyer, the USS Curtis Wilbur, on one of those “freedom of navigation” sails through the Taiwan Strait. The Wilbur’s home port is Yokosuka, a harbor and shipyard south of Tokyo that the U.S. took over shortly after the 1945 surrender and has never since left. Curtis Wilbur, for the record, was a jurist with an abiding interest in the U.S. as a Pacific power and served as secretary of the Navy under Calvin Coolidge.

The Wilbur’s provocative voyage was the second such mission the Pentagon has authorized since Joe Biden took office. The USS John McCain—a lot of strange poetry in these names—made the same journey through the Strait on February 4.

The following day, not to be missed, Secretary of State Antony Blinken had his first telephone conversation with Yang Jiechi. By the State Department’s account, Blinken read China’s top diplomat the riot act, pledging—is “threatening” my word?—“to stand up for human rights and democratic values, including in Xinjiang, Tibet, and Hong Kong.” China, Blinken went on to say, must condemn the recent military coup in Burma. Can you imagine, to linger on one point here, Yang directing Blinken as to what position to take on one or another foreign policy question?

And then, according to Ned Price , the former (presumably) spook who now fronts for the State Department:

The Secretary reaffirmed that the United States will work together with its allies and partners in defense of our shared values and interests to hold the PRC accountable for its efforts to threaten stability in the Indo-Pacific, including across the Taiwan Strait, and its undermining of the rules-based international system.

A lot to unfurl here.

First of all, any notion that Washington will “stand up for human rights and democratic values” in Hong Kong, Xinjiang, and Tibet is patently naïve. From Washington’s perspective, these are merely occasions to exploit in the cause of its propaganda campaign against China.

Second, the thought that China threatens to destabilize the Pacific region is sheer codswallop, as the English picturesquely say—or projection in psychotherapeutic terms. Third, the rules-based international order is, of course, the going euphemism for American hegemony. The U.S. is undermining it quite efficiently on its own, thanks very much, with no assist from the Chinese.

I would love to see a transcript of the Blinken–Yang exchange, as I question whether Blinken spoke in anything like these terms to his Chinese counterpart. In my read he and Ned Price were either lying for domestic consumption or Blinken is an appalling diplomat. (My guess: It is both.) The Chinese account of the conversation, we ought to note, is widely at variance with the State Department’s and, whatever its slant, reflects well on Yang’s dignity.

Be all this as it may or may not be, the events I describe give us in neat outline what we must expect from the Biden administration by way of a China policy. It is grim. As is well documented, Mike Pompeo, Blinken’s thankfully departed predecessor, is to be credited with cranking up hostilities with China to fever pitch. Trump had no taste for geopolitics: It was while he got on with trade disputes that his half-cocked secretary of state brought U.S.–China relations to a condition that approaches the worst of it during the Cold War decades.

Biden and his people had a choice as they dispatched Trump, Pompeo, and all associate kooks from their positions of power. Three choices, actually. They could inherit the Pompeo policy without alteration, they could begin with it but alter it, or they could reject it in favor of a more imaginative, constructive approach to the Sino–U.S. relationship.

They have chosen the first of these alternatives. One might have guessed, given how little Biden, Blinken, and Jake Sullivan, now national security adviser, had to say as Pompeo recklessly pushed the U.S. toward a dangerous confrontation with the People’s Republic.

Just as the new administration sent the McCain through the Taiwan Strait and Blinken picked up the telephone to say whatever he said to Yang Jiechi, The Atlantic Council published “The Longer Telegram: Toward a New American China Strategy.” It is signed by “Anonymous.” This is a preposterous document in all sorts of ways, but we had better scrutinize it for its altogether grim implications.

This is hollow histrionics at its most pitiful, but we must pay attention here, too. The title is a clunky reference to Kennan’s “The Sources of Soviet Conduct,” his 1946 cable from Moscow (where he was chargé d’affaires) to the State Department. Foreign Affairs subsequently published it under the byline “Mr. X,” and it became known thereafter as “The Long Telegram” for its 8,000 words. Kennan’s essay is considered the foundational argument for Washington’s postwar, post–FDR containment policy toward the Soviet Union. He signed it Mr. X in Foreign Affairs for good reason: It was classified.

Any comparison between Kennan’s work, which rested upon a sophisticated, nuanced account of the Soviet perspective, and the Atlantic Council’s extended bit of hawkery is simply silly. This thing demonstrates zero understanding of how the world looks to China: It is, rather, how Washington’s Cold War nostalgists want us—needs us, indeed—to think about how the world looks to China.

From the Council’s forward: “We have maintained the author’s preferred title for the work, ‘The Longer Telegram,’ given the author’s aspiration to provide a similarly durable and actionable approach to China.” Gimme break, as an East European émigré I knew used to say.

I especially love the coy “Anonymous,” as if there is something daring in the publication of this document. It is boilerplate warmongering as we have had it since the Pompeo era. “The author of this work has requested to remain anonymous,” saith the forward, “and the Atlantic Council has honored this for reasons we consider legitimate but that will remain confidential.” Gimme another break.

If there is anything “new” in “The Longer Telegram,” it resides in these following thoughts:

⁋ U.S. policy should center on “Xi [Jinping] and his inner circle” with the intention to make the Chinese leadership fundamentally alter policy and the national direction altogether.

⁋ “The foremost goal of U.S. strategy should be to cause China’s ruling elites to conclude that “it is in China’s best interests to continue operating within the U.S.–led liberal international order.”

⁋ The Chinese leadership must be forced to accept that it cannot “expand China’s borders or export its political model beyond China’s shores.”

Fanciful. Farcical. The first item reeks of 1950s–vintage hyper-ambition that has as much chance of flying today as Hughes’s Spruce Goose. The second and third items reflect an ignorance of Chinese aspirations that is so profound and persistent among the hawks I come to think it must be willful: We need China to have malign designs, it must have malign designs so that the rest of humanity needs us to contain it. And in the absence of any evidence of malign designs, we will incessantly refer to malign designs until evidence is beside the point.

I do not know how much of this dangerous, irresponsible rubbish will get consideration in the Biden White House. But I do not even like worrying about this. At this point, certainly, Blynken and Nod appear to be tilting their China policy in the direction the NATO– and defense industry-funded Atlantic Council urges.

The Biden administration has made its choice on China, then. Now we, we the rest of us, have a choice to make. It is the same choice, not so strangely. Are we going to sit by as Biden and his national-security people draw us into another Cold War? This is our very serious question a little more than a month into Biden’s term. We can judge its seriousness by reflecting back on the disastrous consequences of the waging of the first one—across the Pacific as much as across the Atlantic, let us not forget.

We do not have to go down this road. We could discard the warped perspectives that blind this nation for a clear-eyed, imaginative policy that assesses China’s aspirations and intentions soberly while accepting that American primacy across the Pacific is a thing of the past and now lies beyond retrieval. This “could” is unlikely to be realized, I acknowledge, but I absolutely insist that we establish responsibility for a new Cold War, should it come to one, where it belongs. Which is to say where responsibility for the first one lay, in Washington.

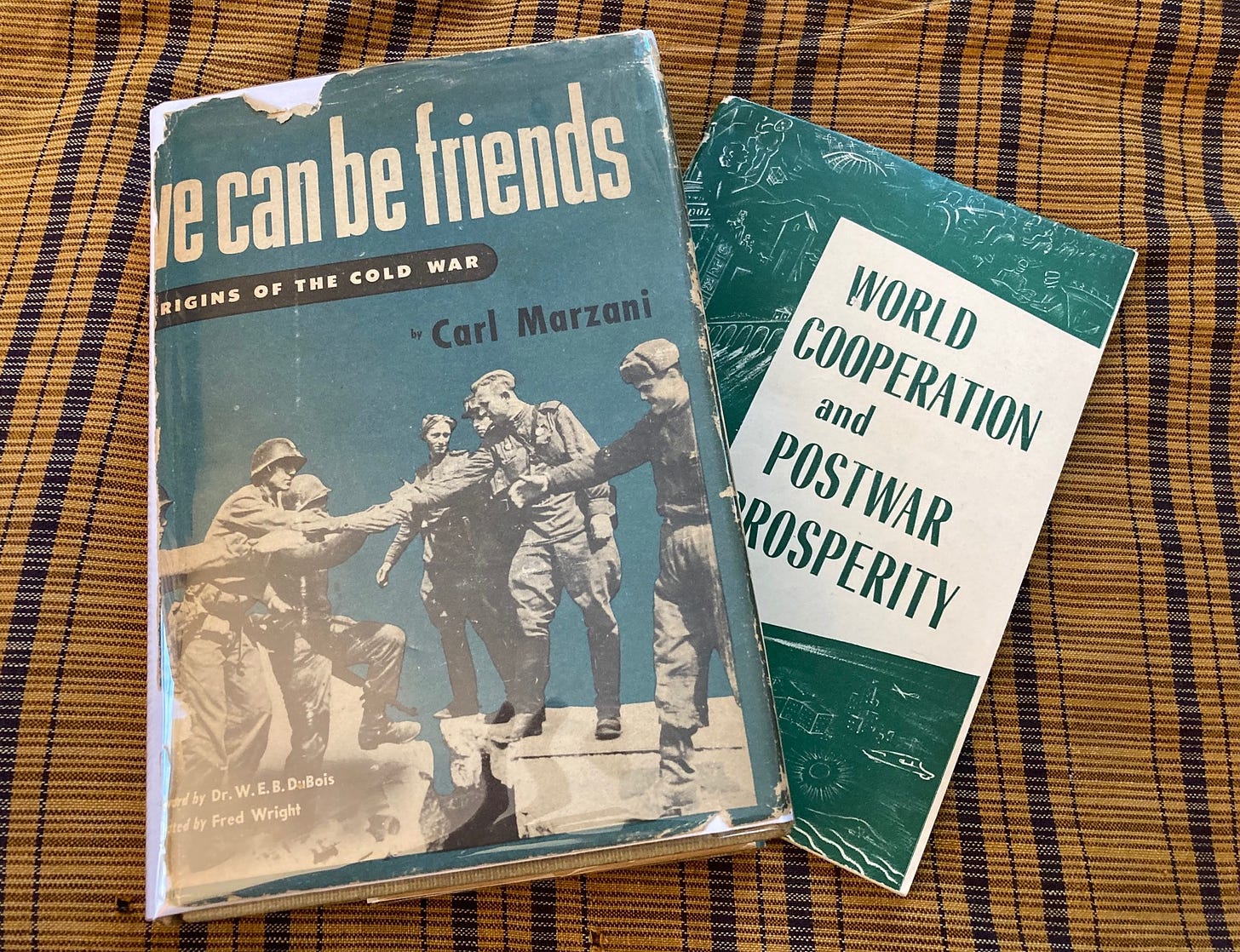

Wholesome family reading.

I have on my bookshelves a few items worth mentioning in this connection. One is a book called We Can be Friends, published in 1952 by Carl Marzani. Marzani was an Italian–American who fought with the Lincoln Brigades in the Spanish Civil War, went on to years of left-wing organizing, and served three years’ time for failing to disclose his political affiliations during his wartime years with the Office of Strategic Services, the CIA’s famous predecessor. If I tell you that We Can be Friends counts as the first revisionist history of the Cold War, assigning responsibility to the Truman administration, the book’s title will then speak for itself. Marzani stood for the orderly co-existence and cooperation FDR intended to pursue with Moscow after the 1945 victories.

A good book, a document expressive of its time—graced with a forward by W.E.B. Du Bois. To my surprise and delight, I discover after 43 years of ownership that my copy is a signed first edition.

Not far from Marzani on my Cold War shelf are two pamphlets by one James S. Allen. Allen was a lifelong leftist historian with an abiding interest in African–American history. In later years he was an editor of the collected works of Marx and Engels, a 50–volume project.

One of these pamphlets, published just before V–E day in January 1945, is called “World Cooperation and Postwar Prosperity.” The second came out three years later as “Marshall Plan—Recovery or War?” The first of these was in the same line as Marzani’s book—an argument for a prolonged settlement with the Soviet Union as the sanest way to a peaceable world order. The second was an effort to explain why the European Recovery Program, advanced by the Truman administration as a selfless humanitarian gesture, ought more accurately to be understood in the context of Truman’s by-then evident plan to set the U.S. on a path to global hegemony.

Marzani and Allen lived in a time not so dissimilar to ours, if we consider American policies toward both Russia and China these past years and that, one or another way, the Biden administration will prove decisive in the evolution of these policies. Marzani and Allen spoke up. They paid for it, Marzani with a prison term, but they said what they judged needed to be said. They understood their moment to be dire. Their truths found their way into the record, and we must be grateful to them for this.

Is our moment as dire as theirs? At the risk of sounding a Cassandra, I would say, “Roughly, and it could get worse from here.” Whatever the degree of certainty on this point, we ought to recognize and accept our responsibilities in our moment as they recognized and accepted theirs in theirs. “If you see something, say something,” as the cops in New York have it.

I will end with a video recorded a couple of summers ago on a little island off the New Hampshire coast. Star Island is one of the Isles of Shoals, specks in the Atlantic 12 or so miles out from Portsmouth. The Star Island International Affairs Conference has been an annual event for a century or so that, over the years, has featured distinguished folk such as Eleanor Roosevelt. Honored I was to be entered into its rolls.

The recording of this speech follows. I titled it “Seeing China as It Is: Recovering Our Sight.” Like Marzani’s book and Allen’s pamphlets, the title ought to speak for itself.