“Sanctions and drift.”

America’s alienating addiction.

Trans–Atlantic drift—the creeping alienation of Americans and Europeans—is nothing new. Certainly it predates Trump—let us be clear on this straightaway. Depending on how one counts, this problem extends back to the mid–Cold War decades, when the Continent became gradually disenchanted with the stark East–West binary Washington insisted upon. President Obama did his part to worsen things when he force-marched the Continent into sanctioning Russia after the coup his administration cultivated in Ukraine seven winters ago.

But the Atlantic grows wider now to the point European leaders speak openly and often of “strategic autonomy.” Just after Christmas (and before Joe Biden’s inauguration) China and the E.U. signed what is commonly judged the most far-reaching investment accord Beijing has ever negotiated. Biden’s foreign policy people, notably Jake Sullivan, the new national security adviser, were immediately aggrieved. Why didn’t those Europeans ask us about it first, Sullivan wondered on Twitter. Memo to Sullivan: Because they knew very well that all you had to say was, “Please don’t,” perhaps without the “Please.”

Over the past several years, it is Washington’s profligate use of sanctions—and their diabolic multiplier, secondary sanctions—that have driven the trans–Atlantic wedge more deeply. European signatories of the Iran nuclear accord—France, Germany, and Britain—remain furious about America’s imposition of sanctions after it withdrew from the pact three years ago this spring: These are sanctions not only against Iran and various Iranians, but against any European company or bank doing business with Iran—those secondary sanctions just mentioned.

As pressing as the Iran question now becomes, the Biden administration must also consider its position on the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline connecting Vyborg, a Russian port on the border with Finland, with the German port of Lubmin/Greifswald, from which Russian gas will be marketed in Western Europe. The Trump administration, in the person of secretary of state Mike Pompeo, was aggressive in declaring sanctions against any European company participating in Nord Stream 2’s construction. What will the Biden administration do with this?

This situation bears watching closely—as does the Iranian question, of course. The Nord Stream 2 controversy has already done further damage to Washington’s relations with the Europeans, not least the Germans. Push this further, and “strategic autonomy” will be the very mildest term for what becomes of trans–Atlantic ties.

While we are but weeks into the Biden administration, safe to say that the U.S. government’s addiction to sanctions is not likely to change anytime soon. The addiction is, as with so much else that is wrong with U.S. foreign policy, completely bipartisan. Over the past decade, presidents from both parties have, with the fulsome backing of establishment Washington, constructed a vast and abstruse sanctions regime targeting not only “official” enemies such as Syria, Russia, Iran, and North Korea; in cases such as Nord Stream 2 they have also been applied to friends and NATO allies.

At Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen’s confirmation hearing last week, Senator Maria Cantwell, the Washington Democrat, claimed, in spite of abundant evidence to the contrary, that “the Trump administration failed to be as aggressive on sanctions”—as aggressive as Cantwell would have liked, we must assume. “I want to be sure,” continued Cantwell, “you use [sanctions] as an economic tool.”

We are not sure where Cantwell has been for the past four years, but the Trump–Pompeo–Steven Mnuchin record in that regard cannot be in dispute: Such was the prior administration’s enthusiasm for this particular tool of economic and geopolitical warfare that it threatened sanctions, including a Draconian 25 percent tariff on automobiles, on European companies that continued to trade with Iran after the U.S. unilaterally pulled out of the Iranian accord in 2018.

Controversy over the construction of the Nord Stream 2 pipeline now starts to assume shrill tones. In spite of a series of sanctions the U.S. has levied against its construction, the pipeline is roughly 95 percent complete. The U.S. and a number of European countries—Denmark and Poland among them—are agitating for a halt to the project, particularly now with the contretemps over Russia’s jailing of the Russian anti-corruption activist Alexei Navalny. This seems likely to reinforce Washington’s givenness to impose sanctions in pursuit of its preferred policy outcomes. In this case, a new series of sanctions on the Nord Stream 2 project will be intended to serve two functions: to pressure Moscow for its alleged human rights abuses while preventing a situation where it is said that Europe becomes “overly dependent” on Russian liquefied natural gas.

The difference between efforts to sanction Russia in 2012 (over the death of the accountant Sergei Magnitsky), in 2014 (over its annexation of Crimea), and in 2016 (over the allegations of election interference) is that this time the Germans have had enough. As experienced Europeanists such as Diana Johnstone have noted, the Europeans are fed up with the heavy-handedness of their traditional ally. “Bitter resentment of arrogant U.S. imposition of its own laws on others has been growing in France, Johnstone observed a few years ago, “and was the object of a serious parliamentary report delivered to the French National Assembly foreign affairs and finance committees… on the subject of ‘the extraterritoriality of American legislation.’”

One has seen examples of the latter for many years in Washington, no matter who was president. But while the E.U. may share some of America’s ambivalence toward Beijing as a strategic competitor, it remains highly resistant to the confrontational (and increasingly militarized) posture toward China that Washington has urged upon them (especially as such confrontation appears to be coming at the European Union’s own economic expense). Europe is increasingly moving to extricate itself from the U.S. security umbrella, whether via proposals to create a new European security policy to boost defense cooperation, or developing an alternative payment system to reduce the dollar’s dominance in the SWIFT payments system (particularly given the recent American proclivity to weaponize SWIFT as a way of punishing what the United States sees as “rogue regimes,” such as Iran).

It was easy to see these underlying tensions in the U.S.–E.U. relationship as purely a consequence of Europe’s often visceral hostility to Donald Trump. But it is increasingly evident that even under an ostensibly more Euro-friendly Biden administration, these tensions are unlikely to go away. In our view, Biden’s national security people have no clue as to how to handle this new set of circumstances.

The just-signed E.U.–China Comprehensive Agreement on Investment, or CAI, was negotiated over seven years in the face of significant opposition from some E.U. member states and American hardliners such as the thankfully departed Pompeo. When Chancellor Merkel pushed the project across the finish line in late December, it was in spite of Jake Sullivan’s ample hints that the new administration would welcome “early consultations” with the E.U. before the deal was done.

This is one of many signals that the old U.S.–E.U. relationship will not now revert to a comfortable status quo ante in which the U.S. is the senior partner. Another is Nord Stream 2. A third, so long as we are at it, is Europe’s disinclination to declare strategic warfare on Huawei, China’s industry-leading maker of 5G telecommunications networks.

Perhaps more significant in the longer term is Germany’s volte-face on 40 years of neoliberal economic orthodoxy. Let us consider this briefly.

A recent piece in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitungfeatured a very public call from Deutsche Bank, Germany’s largest bank, urging sweeping state participation in efforts to reconstruct a new car industry fit for the 21st century, advanced digital applications (in areas such as artificial intelligence), and healthcare provision.

In essence, DB wants to see significant state shares in firms, state participation in funds with private venture capitalists, climate change industries, and other “key technologies.” It goes further by arguing that the state is an ideal vehicle to devise programs to sponsor infant industries that ultimately serve the economic interests of those in the market economy. Fears of increased American and Chinese competition seems to be at the forefront of Germany’s growing opposition to market fundamentalism, at least among some leading policymakers in the country.

As Professor James Galbraith noted in a recent tribute to his father, John Kenneth Galbraith, “One can now map out the rise and decline of nations simply by distinguishing between those that have continued along the lines that once defined U.S. economic success as [J.K.] Galbraith saw it and those that fell under the spell of illusions about free, competitive, and self-regulating markets and under the dominating power of finance.” Over the last half century, the U.S. clearly fell under those market fundamentalist illusions. Galbraith père, a profoundly important intellectual and policy-making figure, ultimately saw his ideas shunned in America.

By contrast, while Germany half-heartedly paid lip service to the operation of a fully free market and the corresponding reduction of state involvement in the formulation of economic policy, Berlin never fully abandoned the Galbraithian principles implicit in its “social market economy.” This structure entailed (in the words of Galbraith fils), “a mixed economy featuring corporations with long time horizons, stable relationships with their bankers and countervailing power,” although it has in more recent times succumbed to the depredations of finance capital, to its vast cost.

As Merkel’s tenure as chancellor comes to an end, it seems apparent that Germany’s future leaders are showing themselves open to the idea of an apparent renewed embrace of a development model of the sort advocated by Friedrich List and Galbraith that effectively counters the so-called “Washington Consensus.”And it is inconceivable that much of the rest of Europe will not follow Berlin’s lead, given Germany’s increasingly powerful role as the E.U.’s first-among-equals.

Accepting multipolarity.

For all of the recent rhetoric about competing with China, or treating Beijing as a “strategic competitor,” the E.U.’s actions, especially Germany’s, seem to be signaling a more pragmatic, less confrontational approach. Maybe this is more along the lines of “if you can’t beat ’em, negotiate,” although such an explanation deprives Europeans of both agency and conviction. Much as the Obama-led policy of sanctioning Russia drove them into a marriage of convenience with China, then, Merkel is now signaling agreement with Chinese President Xi Jinping that a new cold war between East and West is not only other than inevitable; it is also highly undesirable.

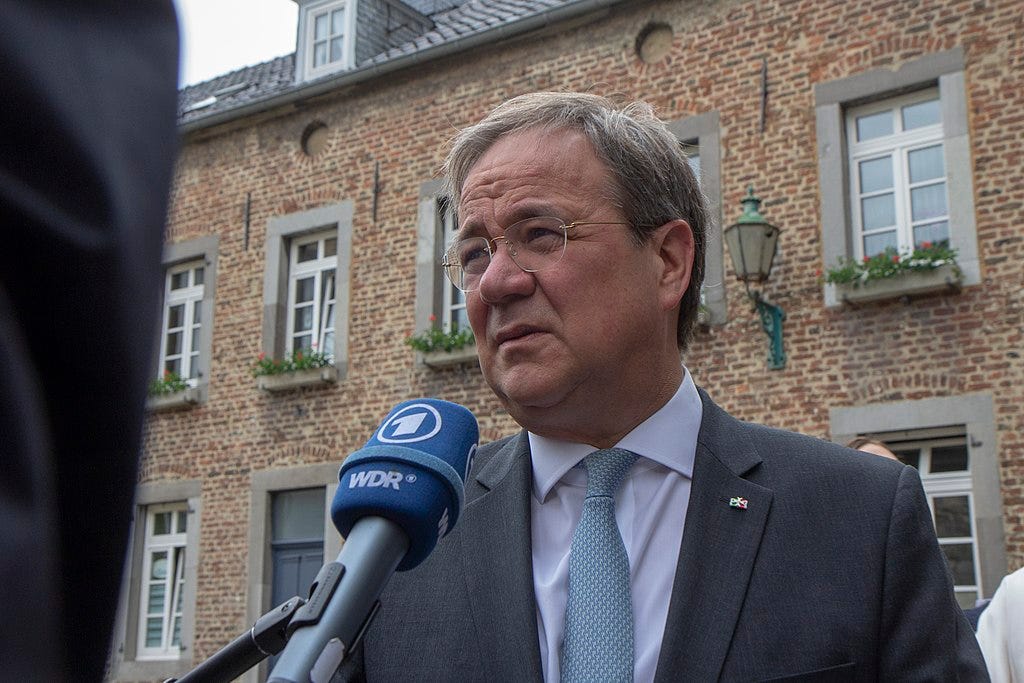

Almost certainly, these trends are likely to continue if, as expected, Armin Laschet, president of the German state of North Rhine–Westphalia and recently elected leader of the country’s Christian Democratic Union, succeeds Merkel as chancellor. In the past, Laschet has shown a healthy skepticism regarding many of the sacred cows of U.S. foreign policy, notably on Syria and Russia, where he has challenged the prevailing Russophobia that now governs Washington’s relations with Moscow. Around the time Russia annexed Crimea, Laschet criticized what he described as the “marketable anti–Putin populism” that was spreading in Germany, according to the Financial Times. And in a classic instance of diplomatic jujitsu, the FT also recycled Laschet’s approving citation of Henry Kissinger on the Russian leader: “Putin’s demonization is not a policy, but an alibi for the absence of one.”

This thinking will almost certainly not be viewed favorably in Washington. But if the Biden administration is to secure any degree of cooperation with the E.U., it must come to accept the impossibility of reconstructing a global framework that makes no accommodation to the world’s emerging multipolarity.

Accepting multipolarity does not mean simply assuming a reversion to Hobbes’s Leviathan world of perpetual conflict. On the contrary, this might bring us closer to the Westphalian ideal of noninterference among nation-states. This used to be an objective of U.S. foreign policy: In WW1 and WW2, America wanted to dissolve the European empires into independent countries whose markets would be open to our exports. Done.

A rich, capitalist, neutral Europe that has no extra–European designs is what the U.S. long wanted. As for the old canard that Europe doesn’t spend enough on its own defense, fine, but according to whose precepts? Unlike the U.S., the E.U. has no military enemies. Russia isn’t going to invade. The Fourth Reich is not going to arise in Germany. The only military they need is a coast guard to keep waves of immigrants in boats from their southern shores and a border patrol sending immigrants back, if this is agreed as the union’s policy. Despite Washington’s incessant protestations that Europe must spend more on defense for its security, it is difficult to avoid concluding that Europe does not “spend enough” because it sees no need to spend more than it does. What is so sacred about that 2 percent of GDP figure anyway, that Biden and his predecessors (including Trump) continued to harp on about? This is a thought so unpopular in Washington it is virtually never considered.

The more fully independent Europe is likely to aim to be a balancing power between East and West—of the latter, open to the former—neutral like the Swiss, but unlike the Swiss, fully engaged in the world. As far as relations with Washington go, it will be transactional: We invest in them, they invest in us. But it won’t be a quasi-colonial relationship in which the American government effectively dictates foreign and, more specifically, defense policy.

From Europe’s perspective there is no need any longer for an American security umbrella, since there are no great-power threats to them, including from China (which simply wants their IP and cash and markets, not their territory). If nothing else, the experience of a once war-torn Europe evolving into a far more stable European Union should suggest that an alternative paradigm is possible if its members seize the opportunity. In the best of outcomes, the thought will eventually light upon the divisive, sanctions-happy U.S., although that seems a bridge too far for the time being.