Patrick Lawrence: The Shadows Descend in Ukraine

Two of my favorite New York Times words are “shadowy” and “murky.” They are brilliantly suited to the Manichean version of our world the Times inflicts daily upon its unsuspecting readers. When The Times terms someone or some society or some chain of events shadowy or murky it scarcely has to do any reporting. Two words more or less without meaning point readers’ minds in precisely the desired direction.

I do not mean to single out The Times in this, except that I do. None of the other major dailies and none of the network broadcasters comes close to the once-but-no-longer newspaper of record in the matter of shadows and murk. This is especially so of the foreign desk, and a murkier corner of American journalism I cannot think of.

There are lots of shadowy people in Russia, The Times will have us know, or think we know. Lots of murky things happen there. Donald Trump’s dealings with the Kremlin were very shadowy, and never mind it turned out there was nothing in them to cast any shadows. Shadows linger long after the lights go on, another of their useful features.

It follows that there are never any shadows and nothing is ever murky among those people or nations the government-supervised Times counts among the “good guys” as opposed to the “bad guys,” and the most powerful paper in America does indulge in such language, if you have not noticed.

We come now to Ukraine. The shadows may be many and the murk very thick, but you will never read of either in The Times. The corruption scandal now erupting in Kyiv and across the country seems to me confirmation that Ukraine has made itself in the post–Soviet era less a nation than a criminal enterprise. This often happens in failed states, where no one believes in anything anymore for the simple reason there is nothing left to believe in. It is then the shadows descend and all grows murky.

This is my read of Kyiv’s latest—of countless—purported efforts to cleanse the pool of corruption in which many of its top officials, most it sometimes seems, have long swum their laps. The Zelensky regime’s announcements of various firings, dismissals, and resignations, late last week and early this, are the merest swab on a gangrene-like disease that has all but consumed what there was of a Ukrainian polity. But worry not. There are no shadows or murk in Ukraine. Volodymyr Zelensky, Washington’s puppet, is the very goodest of the good guys and will get this done.

By the best count I’ve read, in Le Monde and France24, more than a dozen top officials have so far been relieved of duty one way or another. There are a lot of deputies on this list—the level of administrator typically charged with seeing that things get done. The first of these to get the sack was a deputy infrastructure minister named Vasyl Lozynsky, who was arrested Sunday. On Tuesday came the apparently forced resignation of Kirill Tymoshenko, Zelensky’s deputy chief of staff. This brings things quite high in the hierarchy.

And then the long list: a deputy defense minister, a deputy prosecutor, and two other deputies in charge of Kyiv’s provincial development programs. Along with these, the governors of five administrative regions—Kyiv, Sumy, Dnipropetrovsk, Kherson, and Zaporizhzhia—were also fired outright or forced to resign. As France24 points out, the latter three of these regions are active battlefields; Kyiv and Sumy were on the front lines earlier on in the conflict.

Let us gather what facts we have and see what we can make of them.

Vasyl Lozynsky, the infrastructure man, was responsible for restoring the hardware of water, electricity and heating supplies in those areas of Ukraine where either Russian or Ukrainian artillery and rockets had damaged or destroyed them. Plenty of room for patriotic service there, you have to say. Lozynsky is charged with embezzling roughly $400,000 of official funds on behalf of a crime syndicate of which he was a member. Some of these funds were supplied by foreign donors as part of the West’s war effort.

There is the case of Kirill Tymoshenko. A top aide to Zelensky, he has been by the president’s side since he was elected to office four years ago. Close, then. The Times’s explanation for his resignation borders on the cute. Tymoshenko’s transgression was to live a life of conspicuous consumption and “zip around Kyiv,” as The Times put it, in a flash SUV General Motors donated for use in humanitarian projects. This does not sound to me like the nadir of Ukrainian corruption.

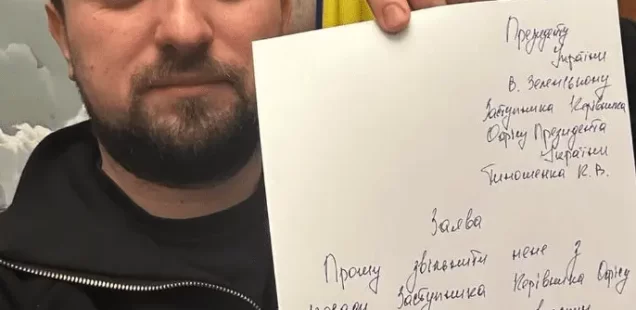

Le Monde’s piece featured a photograph of Tymoshenko with an unmistakable smirk and holding up a resignation letter signed with a heart, exclamation marks, and other less-than-serious scribble. I would not call him a worried man—or a serious man.

The deputy defense minister, Vyacheslav Shapovalov, resigned after a Kyiv weekly, Zerkalo Nedeli, published an investigative piece revealing a kickback scheme wherein Shapovalov’s ministry paid extravagantly over the odds for food intended to supply Ukrainian troops. The fraud—I am reading Le Monde’s account of the Zerkalo Nedeli account—was in the amount of $330 million.

Not much has come out about the others in Kyiv or the provincial governors, but the running theme is impossible to miss. A lot of these people had wartime functions giving them access to funds that were supposed to finance various dimensions of the war effort. Foreign funds would have to be prominent among these, given Kyiv is dead broke. This is in keeping with what we’ve read for many months: The Ukrainian political, security and military cliques are massively ripping off the U.S.

Never mind that. The Times asserted high in its coverage—two stories to date—that all these officials casting no shadows scrupulously avoided stealing any of the billions of dollars the U.S. and the rest of the West are pouring into Ukraine. “There was no sign that the Ukrainian army’s food procurement scandal involved the misappropriation of Western military assistance,” Michael Schwirtz and Maria Varenikova wrote in Wednesday’s editions.

And further on: “The Biden administration is ‘not aware that any U.S. assistance was involved’ in the corruption allegations, the State Department spokesman, Ned Price, told reporters on Tuesday. ‘We take extraordinarily seriously our responsibility to ensure appropriate oversight of all forms of U.S. assistance that we’re delivering to Ukraine,’ he added.”

“No sign,” “not aware”: Know what you are reading, readers. These are elisions. They are not denials. Are we supposed to think Ned Price is going to risk the acquiescence of most Americans if, in the land of no shadows and no murk, the Ukrainians have been misappropriating U.S. taxpayers’ dough? As to the oversight assertion, it is patently false, as that explosive CBS exposé aired last year made perfectly clear. In it we learned that up to 70 percent of the matériel the West ships in via Poland is siphoned into Ukraine’s immense black market in arms.

It is perfectly plain what is going on here by way of the timing. The U.S. has gone from “no lethal arms,” in the years after it sponsored the 2014 to promising, as of this week, main battle tanks. Here is Yuriy Sak, who advises Defense Minister Oleksiy Reznikov, talking to Reuters Thursday:

They didn’t want to give us heavy artillery, then they did. They didn’t want to give us HIMARS [advanced rocket] systems, then they did. They didn’t want to give us tanks, now they’re giving us tanks. Apart from nuclear weapons, there is nothing left that we will not get.

As Sak made clear, the Kyiv regime is about to start pestering the U.S. for F–16 fighter jets. “Not just F–16s,” Sak added with breathtaking impudence. “Fourth-generation aircraft, this is what we want.”

These kinds of statements from officials of Sak’s rank make it bitterly clear that Kyiv is confident the conflict with Russia has landed it with a cash cow that will keep on giving far into the future. Unfortunately, this is an accurate read of the Biden administration’s obsession with destroying the Russian Federation and, in the service of this project, keeping the war going indefinitely.

Think about the Tymoshenko resignation in this context. Here is a man who probably saw Zelensky on a daily basis and enjoyed his boss’s confidence. The expropriated SUV and the expensive living had to be obvious in the presidential circle. Nothing was said for as many as four years. Suddenly, Tymoshenko’s vulgar displays, penny ante as they may be, are just as damaging as the big-time theft at this moment.

I see only one conclusion: We witness a faux purge fashioned to look ruthless when it is nothing more than cosmetic. I do not think Zelensky, to put this point another way, is at all interested in rooting out Ukraine’s structural corruption. There are signs aplenty in his past that he does not stand so supremely far above it.

Zelensky is more a creature of the Biden administration than he is of Washington per se, it seems more accurate to say at this point. The distinction is important. It is very likely the Biden White House—and who knows who runs it these days?—has ordered its puppet to clean up the act, even if it is an act and nothing more.

Victoria “Cookies” Nuland, among the architects of the 2014 coup and an infinitely tolerant patron of the Kyiv regime ever since, made this clear Thursday. “We have been very clear that we need to see, as they prosecute this war, the anti-corruption steps, including good corporate governance and judicial measures, move forward,” she said in Senate testimony. It’s boilerplate, said many times over the years, but it is telling that Nuland is called upon to say it again and now.

Let us not forget: Now that Republicans are a majority in the House, they could any day begin demanding strict accountability for the profligate amounts of weaponry and money the Biden administration is pumping into Ukraine. Kyiv will look shadowy and murky indeed if the newly seated House gets going on this project. This leaves Biden just as vulnerable as Zelensky appears to be.

To turn this dimension of things another way, there are reports here and there that the Biden administration is growing fed up with Zelensky and the mess of corruption, in combination with severe anti-democratic repression, he oversees. I cannot verify these reports and I don’t think anyone can at this moment. But as the war outlook dims, Zelensky’s political fortunes may well dim with them.

There is a deeper, profoundly saddening point to consider as this newest corruption scandal unfolds, and all indications are that it will continue to do so. What kind of people are these? What kind of polity is this? What kind of country is Ukraine?

Kirill Tymoshenko’s nonsense is not altogether nonsense: It is worthy of a few moments’ thought. What kind of man is he to behave as he has in this passage of the Ukrainian story? As to the others, same questions: What kind of man would steal funds meant to keep his own people warm? What kind of man would embezzle the money meant to feed troops defending their country, setting aside on behalf of what?

I have called Ukraine a failed state. I do not think there is any question of this. I have been on the way for some time to concluding Ukrainians are a failed people, too. By this I mean a broken people. The tragic suffering they endured during the Soviet era left deep scars, a kind of national pathology. Did this leave them incapable of making a nation of themselves in the post–Soviet years? I can only pose the question.

It is prompted by what I see now, a failed state wherein many people are left with nothing in which they can believe, where there is nothing to which they can belong. At the top, a sordid greedfest. Everywhere else it is sheer survival in a state of constant anxiety. It is a terrible thing to recognize how utterly inadequate the people running the criminal state of Ukraine are to respond to this moving tragedy.

Amid all the revelations of corruption and the firings and dismissals, Zelensky gave a much-noted speech last weekend to commemorate Ukraine’s Unity Day. “We are all together, no matter where we were born and where we grew up,” he said. “Say today: I will defend my Ukraine. My unity.” The conceit is too thin to hold up at this point and the irony of the moment too great to miss. There is little unity to find among Ukrainians, it seems to me. The nationalism professed by the ruling cliques shapes up as a veil covering up the rampant thievery. The virulent nationalism evident among the far-right political factions and militias, a topic I will take up in future commentaries, seems now to reflect a desperate need to belong in a nation offering nothing in which to belong, to find meaning where there is no meaning.

Your use of the “Cookies” nickname has led to my reading more and more of your excellent articles and I hope to read all you write in the future. Appreciate your highlighting the importance of the human need for submission in explaining so much of the present acquiescence to absurdity in the article where you called on Fromm. Thanks