Europe: The Strings Attached to a Chinese Bailout

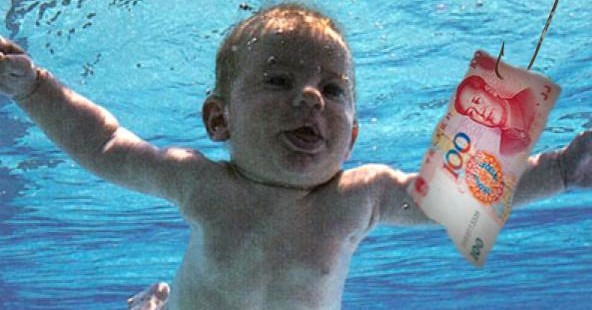

Will your children—or maybe even you—someday find it perfectly natural to put the household savings into the Chinese yuan because it is the world’s safest, steadiest currency? That thought would have been unimaginable even a few months ago. Now we have financial centers around the world—Hong Kong, Singapore, Shanghai, London—competing to become centers of a new trade in offshore yuan.

Not to rub it in, but the idea floated last week that China might ride to Europe’s rescue as it struggles to find a way out of its financial crisis makes the prospect of the yuan as a reserve currency all the more realistic. And what about America and the dollar? The same week Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao offered to help the Europeans, U.S. Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner was practically booed off the podium when he dispensed advice to European finance ministers at a conference in Poland.

It’s a long way from the Asian financial crisis of the late-1990s.. Those with good memories will recall how triumphalist Americans, fresh from their Cold War victory, dispensed advice to every nation from South Korea to Indonesia. There was only one way to do things: Open markets, cut regulation to the bone, adopt austerity measures of a sometimes merciless severity, and privatize every bank and business a government may have had a hand in. The dollar, needless to say, was king back then.

Some of this advice was taken, and some of it was effective despite considerable resistance from labor unions and consumer groups, for instance, in places such as South Korea. But license to preach — by Geithner or any other American official – has been revoked. “I found it peculiar that even though Americans have significantly worse fundamental data than the eurozone, they tell us what we should do,” Maria Fekter,Austria’s finance minister, said after the meeting. “I had expected that [Geithner]…would listen to what we had to say.”

The Chinese are having no such trouble holding people’s attention. Nigeria has already announced that it intends to invest some of its foreign reserves in the yuan, starting this autumn, and Brazil and Chile say they may follow suit. Wang Qishan, the Chinese vice-premier, meanwhile, has just visited London, following Wen Jiabao’s trip a few months ago—an apparent effort to promote trade in offshore yuan in the British financial center. British government officials reportedly say the deal is in the works now.

All this said, it is too soon to look to the yuan as a new global reserve currency. Arvind Subramanian, a noted financial commentator, wrote in the Financial Times recently thatthe yuan as a reserve unit could be a reality within a decade. It is simply not possible. One key to this lies in Wen Jiabao’s offer last week to help Europeans out of their financial morass. It came with strings. And they represent a hard bargain indeed.

At the moment, Europeans classify China as a “non-market” economy, and Wen wants Europe to drop that “non.” That’s his deal. It may sound like a minor technicality, but the difference would be significant. As a non-market economy, China’s exports to Europe are subject to tariffs if they are judged unfairly inexpensive. It is almost impossible to impose such tariffs on goods coming from a market economy.

Wen’s request tells us something important. China remains what scholars call a capitalist development state, a CDS in the jargon (not to be confused with a credit default swap). In a CDS, the government is not a neutral entity, present to regulate the economy but otherwise stay out of it. A CDS assigns the government a far more prominent role: It acts to allocate funds; it encourages what it judges “strategic industries”—cars, electronics, and banking are examples in the Chinese case.

We have learned a few things about CDSs since the late Chalmers Johnson identified Japan as one back in the 1980s. For one thing, control of the currency is a tool the CDS uses to manage the economy. For another, a CDS is not necessarily a kind of way-station on the road to becoming a fully open-market economy. It is an alternative model, and while some gradual liberalizations may occur, the model remains fundamentally at odds with the free-market economics the U.S. advocates and even the social-market model some Europeans favor.

Conclusions: First, China is nowhere near prepared to let the yuan float on international markets to the extent it would have to if it were to trade in any volume in a financial center such as London. It’s not ready in terms of either its policies or its institutions.

Second, Europeans would be fools to accept a Chinese rescue, tempting as one may be, on Wen Jiabao’s terms. And if Geithner demonstrated anything during his appearance in Poland last week, it is that the Europeans are nobody’s fools in the end.