American exceptionalism is a dangerous myth

Move beyond Tea Party lies and phony patriotism. This Memorial Day, let’s remember our history honestly

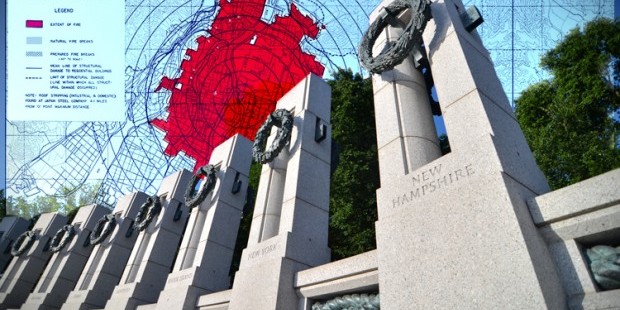

At one end of the Reflecting Pool in Washington, D.C., in the expanse between the Washington Monument and the Lincoln Memorial, the Bush administration authorized a memorial to World War II. This was a matter of months before the events of September 11. It seemed a strange design when it was first shown in the early summer of 2001, and so it proved when the monument was finished and open to the public in 2004. It consists of fifty-six granite pillars arranged in two half-circles around a pool, each pillar standing for a state or territory, each endowed with a bronze wreath. Each side of the entranceway—graceful granite steps down to the level of the pool—is lined with a dozen bas-relief bronzes depicting important moments in either the European or the Pacific war. At the opposite end of the small circular pool, a “freedom wall” commemorates the 400,000 American dead with 4,000 gold stars.

This message, chiseled into a stone tablet, greets the visitor to the World War II Memorial:

Here in the presence of Washington and Lincoln, one the eighteenth-century father and the other the nineteenth-century preserver of our nation, we honor those twentieth-century Americans who took up the struggle during the Second World War and made the sacrifices to perpetuate the gift our forefathers entrusted to us, a nation conceived in liberty and justice.

One must spend a certain time at the memorial to grasp the message it is conveying.This has to do with the monument’s style, as the bas-relief bronzes and the welcoming inscription suggest. This is not a memorial built by people of the early twenty-first century. Part of its purpose, indeed, is to erase all that Americans did between 1945 and 2001 so that we might insert ourselves into the morally pure era (supposedly, as we have reimagined it) of the Second World War. It functions, then, a little like Williamsburg or Sturbridge Village: It is history that is not-history, or not-history dressed up as history. It is history, in short, for those who are devoid of memory. The architect—Friedrich St. Florian, whose studio is in Rhode Island— accomplished this by designing in the style sometimes called modern classical. The modern classical style was popular in the 1930s and forties. It is characterized by mass and volume in its forms and simplified articulations of minimal detail. Roosevelt might have built in this style, as Stalin or Mussolini might have.

St. Florian’s project, then, is a monument to forgetting, not remembering. There is no bas-relief dedicated to the atomic bomb attacks on Japan or the fire-bombings in Germany; all that occurred after 1945 disappears into the memorial’s antiquated style. We have a hint of this if we consider the date of its conception and construction. The first decade of our new century was marked by a strong, quite evident nostalgia for the Second World War. One found it in best-selling books (“The Greatest Generation”) and in popular films (“Pearl Harbor,” “Schindler’s List”). The monument is of a piece with these cultural productions. It is a memorial as we imagine such a thing would have been made at the time being memorialized. It is a reenactment of a sorrow that is beyond us to feel now. One cannot say this about the other monuments ranged around the Reflecting Pool. They are not reenactments; they are not in quotation marks. In this case, one is placed back in the 1940s so as to see the forties. It is history for people who cannot connect with history. Nostalgia is always an expression of unhappiness with the present, and never does it give an accurate accounting of the past. What are we to say about a monument to a nostalgia for nostalgia?

* * *

The various symptoms of America’s dysfunctional relationship with its past are all in evidence in the Tea Party, the political movement formed in 2009 and named for the Boston Tea Party of 1773. It would be remiss not to note this. Much has been written about the Tea Party’s political positions: Its members are radically opposed to taxation and favor a fundamentalist idea of the infallibility of markets and an almost sacramental interpretation of the Constitution. They cannot separate religion from politics, and they consider President Obama either a socialist or a Nazi or (somehow) both. They hold to a notion of the individual that the grizzliest fur trapper west of the Missouri River 170 years ago would have found extreme. When the Tea Party first began to gather national attention, many considered it a caricature of the conservative position that held too distorted an idea of American history to last any consequential amount of time. Plainly this has been wrong, at least so far, given the number of seats the movement won in the legislative elections of November 2010: At this writing, they number sixty-two in the House of Representatives.

“Take our country back” is among the Tea Party’s more familiar anthems. And among skeptics it is often asked, “Back to what?” I have heard various answers. Back to the 1950s is one, and this is plausible enough, given the trace of the movement’s bloodlines back to the John Birch Society and others among the rabidly anticommunist groups active during the Cold War’s first decade. But the answer I prefer is the eighteenth century—or, rather, an imaginary version of the eighteenth century. A clue to the collective psychology emerged in the movement’s early days, when adherents dressed in tricorn hats, knee breeches, and brass-buckled shoes. This goes to the true meaning of the movement and explains why it appeared when it did. One cannot miss, in the movement’s thinking and rhetoric, a desire for a mythical return, another “beginning again,” a ritual purification, another regeneration for humanity.

Whatever the Tea Party’s unconscious motivations and meanings—and I count these significant to an understanding of the group—we can no longer make light of its political influence; it has shifted the entire national conversation rightward—and to an extent backward, indeed. But more fundamentally than this, the movement reveals the strong grip of myth on many Americans—the grip of myth and the fear of change and history. In this, it seems to me, the Tea Party speaks for something more than itself. It is the culmination of the rise in conservatism we can easily trace to the 1980s. What of this conservatism, then? Ever since Reagan’s “Morning in America” campaign slogan in 1984 it has purported to express a new optimism about America. But in the Tea Party we discover the true topic to be the absence of optimism and the conviction that new ideas are impossible. Its object is simply to maintain a belief in belief and an optimism about optimism. These are desperate endeavors. They amount to more expressions of America’s terror in the face of history. To take our country back: Back to its mythological understanding of itself before the birth of its own history is the plainest answer of all.

I do not see that America has any choice now but to face this long terror. America’s founding was unfortunate in the fear and apprehension it engendered, and unfortunate habits and impulses have arisen from it. These are now in need of change—a project of historical proportion. Can we live without our culture of representation, our images and symbols and allusions and references, so casting our gaze forward, not behind us? Can we look ahead expectantly and seek greatness instead of assuming it always lies behind us and must be quoted? Can we learn to see and judge things as they are? Can we understand events and others (and ourselves most of all) in a useful, authentic context? Can we learn, perhaps most of all, to act not out of fear or apprehension but out of confidence and clear vision? In one way or another, the dead end of American politics as I write reminds us that all of these questions now urgently require answers. This is the nature of our moment.

* * *

In some ways the American predicament today bears an uncanny resemblance to that of the 1890s. At home we face social, political, and economic difficulties of a magnitude such that they are paralyzing the nation and pulling it apart all at once. Abroad, having fought two costly and pointless wars since 2001, we are challenged to define our place in the world anew—to find a new way of venturing forth into it. The solutions America chose a century ago are not available to us now. But the choices then are starkly ours once again.

Our first choice is to accept the presence of these choices in our national life. This is a decision of considerable importance. To deny it is there comes to a choice in itself—the gravest Americans can make. When America entered history in 2001, it was no one’s choice, unless one wants to count Osama bin Laden. This means that America’s first choice lies between acceptance and denial. The logic of our national reply seems perfectly evident. To remain as we are, clinging to our myths and all that we once thought made us exceptional, would be to make of our nation an antique, a curiosity of the eighteenth century that somehow survived into the twenty-first. Change occurs in history, and Americans must accept this if they choose to change.

But how does a nation go about accepting fundamental changes in its circumstances—and therefore its identity, its consciousness? How does a nation begin to live in history? In an earlier essay I wrote about what a German thinker has called the culture of defeat and its benefits for the future. Defeat obliges a people to reexamine their understanding of themselves and their place in the world. This is precisely the task lying at America’s door, but on the basis of what should Americans take it up? “Defeat” lands hard among Americans. The very suggestion of it is an abrasion. We remain committed to winning the “war on terror” Bush declared in 2001, even if both the term and the notion have come in for scrutiny and criticism. Who has defeated America such that any self-contemplation of the kind I suggest is warranted?

The answer lies clearly before us, for we live among the remains of a defeat of historical magnitude. We need only think carefully to understand it. We need to think of defeat in broader terms— psychological terms, ideological terms, historical terms. We need to think, quite simply, of who we have been—not just to ourselves but to others. Recall our nation’s declared destiny before and during its founding. The Spanish-American War and all that followed—in the name of what, these interventions and aggressions? What was it Americans reiterated through all the decades leading to 2001—and, somewhat desperately, beyond that year? It was to remake the world, as Condoleezza Rice so plainly put it. It was to make the world resemble us, such that all of it would have to change and we would not. This dream, this utopia, the prospect of the global society whose imagining made us American, is what perished in 2001. America’s fundamentalist idea of itself was defeated on September 11. To put the point another way, America lost its long war against time. This is as real a defeat as any other on a battlefield or at sea. Osama bin Laden and those who gave their lives for his cause spoke for no one but themselves, surely. But they nonetheless gave substantial, dreadful form to a truth that had been a long time coming: The world does not require America to release it into freedom. Often the world does not even mean the same things when it speaks of “freedom,” “liberty,” and “democracy.” And the world is as aware as some Americans are of the dialectic of promise and self-betrayal that runs as a prominent thread through the long fabric of the American past.

Look upon 2001 in this way, and we begin to understand what it was that truly took its toll on the American consciousness. Those alive then had witnessed the end of a long experiment—a hundred years old if one counts from the Spanish war, two hundred to go back to the revolutionary era, nearly four hundred to count from Winthrop and the Arbella. I know of no one who spoke of 2001 in these terms at the time: It was unspeakable. But now, after a decade’s failed effort to revive the utopian dream and to “create reality,” ww would do best not only to speak of it but to act with the impossibility of our inherited experiment in mind—confident that there is a truer way of being in the world.

* * *

Where would an exploration rooted in a culture of defeat land Americans, assuming such an exercise were possible? That it would be a long journey is the first point worth making. There is time no longer for our exceptionalist myths, but to alter our vision of ourselves and ourselves in the world would be no less formidable a task for Americans than it would be (or has been) for anyone else. History suggests that we are counting in decades, for there would be much for Americans to ponder—much that has escaped consideration for many years. History also suggests that the place most logically to begin would be precisely with history itself. It is into history, indeed, that this exploration would deliver us.

In the late 1990s, a time of considerable American triumphalism at home and abroad, the University of Virginia gathered a group of scholars, thinkers, historians, and writers to confer as to an interesting question.The room was filled with liberals and left-liberals.Their question was, “Does America have a democratic mission?”

It seemed significant even that the topic would be framed as a question. Would anyone in Wilson’s time have posed one like it? This would not, indeed, have been so just a few years earlier—or a few years later. But it was so then, a line of inquiry launched not quite a decade after the Cold War’s end, three years before the events of September 11. Not so curiously, many of those present tended to look to the past. Van Wyck Brooks’s noted phrase, “a usable past,” was invoked: If we are to understand our future, and whatever our “mission” may be, we had better begin by examining who we have been.

Any such exercise would require a goodly measure of national dedication. It would require “a revolution in spirit,” as the social historian Benjamin Barber has put it. But it would bring abundant enhancements. It would begin to transform us. It would make us a larger people in the best sense of the phrase. There is a richness and diversity to the American past that most of us have never registered. Much of it has been buried, it seems to me, because it could not be separated from all that had to be forgotten. Scholarship since the 1960s has unearthed and explored much of this lost history. But scholarship—as has been true for more than a century—proceeds at some distance from public awareness. We now know that the Jeffersonian thread in the American past, for instance, was much more complex, more dense and layered, than Americans have by tradition understood it. In the supposed torpor of the early nineteenth century we find variations of political movements as these were inherited from England. We find among the Democrats the roots of the Populists, the Progressives, democratic socialists, and social democrats. These groups were not infrequently the product of ferment within the liberal wings of various Christian denominations. There was nothing “un-American” about any of them, and all of them were at least partly historicist: They saw America as it was and as it was changing. They understood the need for the nation to move beyond its beginnings to take account of the new.

One need not subscribe to the politics of these or any other formations in history to derive benefit from an enriched and enlivened knowledge of them. They enlarge and revitalize the American notion of “we.” And in so doing, history opens up more or less countless alternatives—alternative discourses, alternative ideas of ourselves, alternative politics, alternative institutions. All this is simply to cast history as a source of authentic freedom. At the moment our standard view of the American past lies behind us like a “flattened landscape,” as one of our better historians put it some years ago. We are thus unaccustomed to a depth and diversity in our past that present us with a privilege, a benefit, and a duty all at once.

Could Americans bear an unvarnished version of their past—a history with its skin stripped back? History as we now have it seems necessary to bind Americans, to make Americans American. Think merely of the twentieth century and all the wreckage left behind in it in America’s name, and it is plain that the question is difficult and without obvious answers. But something salutary is already occurring in our midst. Historians of all kinds have begun new explorations of the past. There are African-American projects, Native American projects, projects concerning foreign affairs, diplomacy, war, and all the secrets these contain. This is the antitradition I mentioned in an earlier essay coming gradually into its own. It is remarkable how sequestered from all this work our public life has proven.The temptations of delusion are always great, and most of America’s political figures succumb to them. But time will wear away this hubris. In the best of outcomes, the antitradition will be understood as essential to understanding the tradition.

I once came across a small but very pure example of a nation altering its relation to its past. It was in Guatemala. The long, gruesome civil war there, which ended in the 1990s, had made of the country at once a garden of tragic memories and a nation of forgetters.The Mayans were virtually excluded from history,as they always had been, and the country was deeply divided between los indigenes and those of Spanish descent.

Then a journalist named Lionel Toriello, whose forebears had been prominent supporters of the Arbenz government in the 1950s (until Americans arranged a coup in 1954), assembled two million dollars and 156 historians. They spent nearly a decade researching, writing, editing, and peer-reviewing work that was eventually published as a six-volume Historia General de Guatemala. Its intent was “pluralistic,” Toriello explained during my time with him. It provided as many as three points of view on the periods and events it took up. So it purported to be not a new national narrative so much as an assemblage of narratives from which other narratives could arise. It was a bed of seed, then. Inevitably, Toriello’s project had critics of numerous perspectives. Unquestionably, the Historia General was the most ambitious history of themselves Guatemalans had ever attempted.

It was an unusual experiment. One of the things Toriello made me realize was that one needs a new vocabulary if one is to explore the past, render it in a new way, and then use it to assume a new direction. A culture of defeat requires that the language must be cleansed. All the presumption buried in it must be identified and removed. Another thing Toriello showed me was that this could be done, even in a small nation torn apart by violence and racial exclusion. The renovated vocabulary arises directly from the history one generates.

None of this, it seems to me, is beyond the grasp of Americans. To consider it so is merely to acknowledge the extent to which the nation famous for its capacity to change cannot change. It is to give in to the temptations of delusion. I do not think “change” took on so totemic a meaning during Barack Obama’s 2008 campaign by coincidence. I also think the ridicule of this thought coming from Obama’s critics bears interpretation. Change is a testament to strength. But as so often in the past, Americans came to fear what they desired, causing many to take comfort in the next set of constructed political figures promising that, no, nothing at all need change.

An inability to change is symptomatic of a people who consider themselves chosen and who cannot surrender their chosenness. When we look at our nation now, do we see the virtuous republic our history has always placed before us as if it were a sacred chalice? The thought seems preposterous. America was exceptional once, to go straight to the point. But this was not for the reasons Americans thought of themselves as such. America was exceptional during the decades when westward land seemed limitless—from independence until 1890, if we take the census bureau’s word for the latter date. For roughly a century, then, Americans were indeed able to reside outside of history—or pretend they did. But this itself, paradoxically, was no more than a circumstance of history. Americans have given the century and some since over to proving what cannot be proved. This is what lends the American century a certain tragic character: It proceeded on the basis of a truth that was merely apparent, not real. Do Americans have a democratic mission? Finally someone has asked. And the only serious answer is, “They never did.