“Weak minds.”

Oligarchs and their scapegoats.

This is the second of a two-part series on the causes of America’s decline—economic, industrial, social, spiritual—and two prominent intellectuals who address themselves to remedies. Part 1 can be found here.

From secrecy and deception in high places, come home, America. From military spending so wasteful that it weakens our nation, come home, America.

—— George McGovern

Peter Thiel made his initial fortune by cofounding (and then selling) the electronic-payments service PayPal. Since that time, Thiel has created various other enterprises, ranging from venture-capital firms such as Founders Fund to a data-analysis firm named Palantir. In addition to his success as a venture capitalist, Thiel is member of the steering committee of the Bilderberg Meeting, an annual conference where European and American elites discuss how to maintain and promote free-market capitalism. He supported Donald Trump’s presidential campaign, a highlight of which was Thiel’s delivery of a pro–Trump speech at the Republican National Convention in July 2016. In that speech, Thiel explained Trump’s rise as a response to national decline resulting from the damaging consequences of free trade, out-of-control militarism, increasingly expensive health care, rising student debt, and stagnant wages. Jamie Galbraith, as noted in Part 1 of this essay, shares many of these concerns.

Thiel’s explanation for our national decline has been delivered, with much more detail, in various other formats over recent years. An essay Thiel wrote for the National Review (2011) elaborates his declinist viewpoint. In that essay, “The End of the Future,” Thiel argues that technological and scientific progress, the basis for economic growth, has stalled out. The lack of innovation in energy, agriculture, medicine, and science in general, he contends, has cut into standards of living that can no longer be attenuated by accumulation of consumer debt and cheap goods from free-trade partners, particularly China. Even gains in the digital tech sector, where Thiel made his initial fortune, he explains as having stalled out and now amount to illusory productivity.

So far, Galbraith and Thiel seem to be traversing similar paths, especially as regards the impediments to growth of rising resource costs and increased digitization. However, Thiel diverges from the progressive Galbraith and speculates that the decline in technological innovation has been concealed by battles over identity politics. It is here Thiel begins to bring questions of culture and psychology into his inquiry. As he puts it:

Today’s aged hippies no longer understand that there is a difference between the election of a black president and the creation of cheap solar energy; in their minds, the movement towards greater civil rights parallels general progress everywhere.

Thiel fleshed out his proposal for dealing with this decline in a speech delivered at the first National Conservativism Conference, in July 2019. In “The Star Trek Computer Is Not Enough,” he retraces the ground covered in his earlier National Review essay while also exploring new themes. He assails Silicon Valley for its lack of innovation and its too-close-for-comfort relationship with China, while also attacking China for its unfair trade practices.

Later in the speech, Thiel also delivers a jeremiad against higher education for handing out overrated, grade-inflated educations and saddling students with debt. He claims that, as mentioned in the National Review piece, the American left ignores national decline by obsessing about identity politics, while the right is in a state of denial about national decline as it insists that the U.S. is “exceptional” and immune to such decay. This is Thiel’s argument for registering a psychological component in any effort to achieve the national solidarity necessary to channel government resources into reversing decline. Indeed, Thiel, who is known for his adherence to libertarian philosophy, acknowledges that government in the past was capable of achieving amazing feats, such the Manhattan Project and the Interstate Highway System. Its shambolic response to the Covid–19 pandemic stands as tragic testimony to the lapse of “can-do” America.

What, then, is this psychological factor that can reverse our national decline, so overcoming the hurdles on right and left? This is Thiel’s question. His reply appears to be the use of René Girard’s famous scapegoat mechanism to break a societal bottleneck.

● ● ●

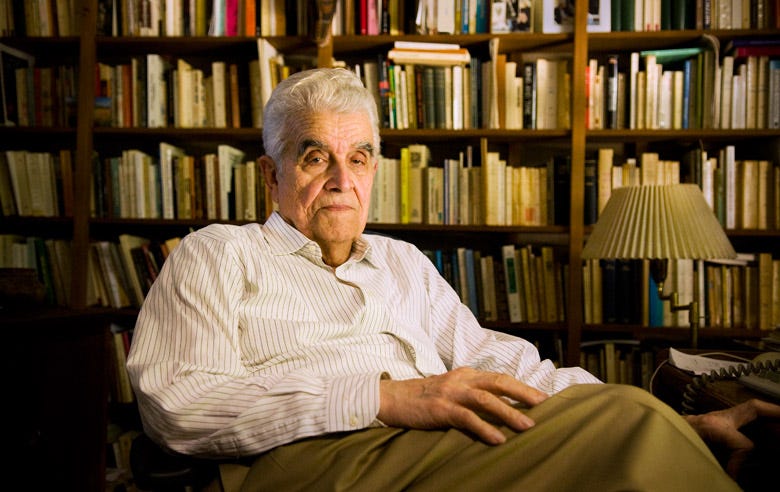

René Girard was a French polymath who made intellectual contributions to a wide variety of fields, ranging from philosophy to anthropology. He is best known for his theories of mimetic desire and the scapegoat mechanism. Mimetic desire is the theory that mimicry (imitation) is fundamental for human society. It is necessary to acquire skills, as in an apprenticeship, but left unchecked, unrestricted mimesis causes us to covet what others have. This Girard calls mimetic desire. Desire of this kind can escalate and lead to conflict and violence. In essence, a contradictory conflict of societal messaging (mimicry is necessary, mimicry is dangerous) results in what fellow polymath Gregory Bateson called a double bind.

Girard’s solution to nullifying this double bind is his other well-known intellectual contribution: the just-mentioned scapegoating mechanism. According to Girard, society nullifies the Batesonian double bind by committing what is called a Logical Types error (a member of a group taken to represent the entire group) and assigning blame to an innocent victim called a scapegoat. Consequently, if the scapegoat is sacrificed, the potential for violence can be discharged and societal cohesion maintained. A good example of scapegoat theory is Christianity itself. Jesus represents a vessel of sorts, taking upon himself the sins of mankind and extinguishing them upon his death on the cross.

Peter Thiel has acknowledged Girard’s impact on his life and way of thinking (here and here), and he even spoke at a memorial service for Girard after he died. Although Thiel does not acknowledge doing so, it appears he has taken Girard’s insights and applied them to the political realm. In effect if not by conscious design, he has selected as collaborative scapegoats Google, the politically correct “left,” and China. It appears that Thiel, and fellow travelers such as Missouri Senator Josh Hawley, want to rally the fractious American people (as FDR did in is time) by focusing their anger on enemies, foreign and domestic, to generate unity and get the populace to consent to great technological innovations underwritten by the government while being distracted from the true reasons for our inability to progress technologically and economically. If the culprits above are scapegoats in the Girardian sense, to what degree is the blame laid upon them false, and what true culprit is Thiel distracting from?

As Galbraith pointed out in The End of Normal, the era of solid economic growth from the end of World War II to the two oil shocks of the 1970s has been behind us for quite a while. What we in the U.S. experience now is a consequence of the end of that solid growth era: a country ruled by corporate elites who have captured the machinery of government to enrich themselves at the expense on non-elites. This is what Galbraith calls the predator state. These predatory oligarchs and their rule of the country are what Thiel, a billionaire, seems to want to distract from while simultaneously drumming up anger against his coalition of scapegoats to make possible great technical and scientific projects underwritten by the government. What about Thiel’s scapegoats, then?

Thiel has made the accusation that Google is committing treason by working for the Chinese government on AI research, spurning working with the U.S. government, and should be investigated by the FBI and the CIA. It appears, however, that Thiel, as a libertarian, harbors an ideological opposition to AI and is ideologically and personally given to cryptocurrencies, Bitcoin in particular. As Thiel said in an interview with LinkedIn founder Reid Hoffman:

Crypto is decentralizing, AI is centralizing. Or, if you want to frame it more ideologically, crypto is libertarian and AI is communist.

There is a further irony in that Thiel’s company, Palantir, is utilized by various U.S. government agencies for data collection and surveillance, an apparent contradiction for an ideological libertarian.

What of the PC left and its obsession with identity politics? There may be a kernel of truth to Thiel’s accusation that the American left’s obsession with identity politics conceals the lack of material progress in the U.S. since the end of the era of solid growth. Intellectuals on the left, such as the American literary theorist Walter Benn Michaels and political scientist Adolph Reed, have long criticized leftist obsessions with identity politics as a neoliberal weapon to distract from issues of class and economic inequality. It is hard to believe that the CIA, with its long history of opposing anything remotely resembling leftist policy, or the Pinkertons, with their track record of terrorizing labor unions, have gone woke for the sake of social justice. Thiel has taken this issue, grounded in reality, and intertwined it with his dislike of his ideological enemies, Google and China. As he stated in an interview with conservative TV personality Tucker Carlson:

There’s probably a broad base of Google employees that are ideologically super left wing, sort of woke, and think that China’s better than the U.S. or that the U.S. is worse than China.

We arrive at the dominant scapegoat in Thiel’s playbook: China. Like Thiel’s accusation against the left, his scapegoating of China has kernels of truth in it. There were warnings about the dangers of free-trade agreements in the early 1990s. Sir James Goldsmith, financier and politician, cautioned about the dangers in his books The Trap and The Response. In particular, Goldsmith was concerned about the negative effects of labor arbitrage on the fabric of Western societies and even had a prescient warning about China’s ability to provide Western corporations with a massive reservoir of cheap labor and run large trade surpluses:

China is determined to recapture its preeminence in Asia and to make itself so strong that it will never again be subjected to perceived slights or indignities from the West. If it keeps itself together, it will become a great world superpower, geopolitically, militarily, and economically.

Goldsmith published this thought in 1995. Fast forward to 2020: China is by some measures the world’s largest economy, the world’s leading manufacturing economy, and largest exporter of goods. It has ambitious plans (Made in China 2025) to move beyond dominance in manufacturing cheap goods and dominate high-tech industries such as robotics, artificial intelligence, and biotechnology.

So it appears Thiel’s focus on China is not without merit. But he seems intent on taking a highly competitive rival and converting it into an enemy of the U.S., as evidenced his numerous speeches and interviews about China. Adversary and competitor are two different things. There is a bit of blame deflection here, as it was U.S. corporations and their owners who chose (and were not forced) to engage in free trade with China, taking advantage of its massive army of cheap labor and nonexistent safety standards for profit—and thus abetting China’s growth into a formidable economic powerhouse.

● ● ●

If we are to accept Galbraith or Thiel in their respective explanations for decline and their propositions for reversal, then the U.S. has two paths before it: a moderate approach using New Deal Lite economic mechanisms to achieve a slow yet growing economy—this appears to be the Biden administration’s strategy—or a bold, risk-taking approach to governance that relies on the primordial scapegoating mechanism described by René Girard. This could arguably be identified as the Trump administration’s way at our problems.

The major issue with Galbraith’s progressive approach is that the solidarity needed to achieve even the slow-growth approach he advocates is notoriously absent. This is the missing psychological factor that Galbraith acknowledged was necessary for a large-scale Keynesian intervention and is a critical limiting factor in this weaker case as well. Indeed, it was only the threat of the rising fascist tide that united the citizenry and enabled FDR to ramp spending to levels that ended the Great Depression in America. The looming threat of environmental devastation from climate change would seem to have the necessary properties needed to unify the populace, but, so far, America continues to fiddle while a large portion of the West burns and other sections of the country are hammered by record flooding.

The current divide between the American left and right appears to be an unbridgeable, ever-widening gap, making bipartisan electoral support for Galbraithian reform measures extremely unlikely. President Biden, the eventual victor of the 2020 presidential election, currently his finds his domestic ambitions blocked by an increasingly belligerent Republican Party, rebellious conservative Democrats, and Biden’s innate centrist impulses, not to mention his continued bungling as the nation combats Covid–19. Therefore, due to partisan divisions, conservative restraint among centrist democrats, and lack of a unifying threat, it seems that the Galbraithian approach is doomed to fail.

It appears that Thiel notes this weakness in collective psychology and goes on to exploit the left’s fractious state. In brilliant, aikido-like fashion, he converts it into a domestic scapegoat (part of what his ally Josh Hawley calls the “cosmopolitans”) to unite the right and political moderates—and distract, essential to note, from the corporate oligarchy. In addition to taking advantage of the left’s division by employing the scapegoat mechanism, Thiel targets China, bundled together with the ineffectual left and technical rival Google, as a replacement for the old Cold War scapegoat, the defunct Soviet Union. The Soviet threat, however formidable or otherwise, induced a level of domestic political cooperation and national unity that allowed for great endeavors such as the aforementioned Interstate Highway Program, so this method has a proven track record.

One flaw in Thiel’s approach is that, as Galbraith points out, the material conditions that allowed for ambitious, Manhattan Project-level investments are no longer present. What government programs might have to be sacrificed to achieve such endeavors? Thiel himself states in the aforementioned “The End of the Future” essay:

I am not aware of a single political leader in the U.S., either Democrat or Republican, who would cut health-care spending in order to free up money for biotechnology research—or, more generally, who would make serious cuts to the welfare state in order to free up serious money for major engineering projects.

This connects to another potential flaw in Thiel’s scheme: Will the psychological advantage of Thiel’s strategy be sustainable if, say, what remains of the social safety net is sacrificed for such purposes? Why the focus on cutting the social safety net? Why not reroute spending from a wasteful (and ineffective, as argued by Galbraith) military to bolster industrial R&D ambitions. Is it because Thiel is a beneficiary of military-industrial complex largesse?

The truth of the matter is that Thiel, if he is truly concerned about national wellbeing, needs to look at the true culprit behind American decay: his fellow oligarchs, with their decades-long assault on workers and public goods, instead of scapegoating the woke “left” and pushing for war with China. Thiel has already demonstrated some capacity to reject herd thinking, as he has rejected the aversion to government supported industrial policy. Is he open-minded enough and/or brave enough to consider that reversing decline may require, as FDR once proudly boasted, to become a traitor to his class? Would Thiel dare fund and support, say, the effort by Amazon workers to unionize? At this moment, it does not look like Thiel is willing to traverse such a path. Thiel-supported senatorial candidates such as J.D. Vance and Blake Masters continue, in a bit of Girardian irony, to mimic Thiel’s scapegoating of the woke left, Big Tech, and China.

Does Thiel nurse a mimetic desire for what China—with its social cohesion, manufacturing capacity, and ability to plan—is able to accomplish and the U.S. cannot any longer? If Thiel wants to learn how China leapfrogged the U.S., a suggestion would be to read Isabella Weber’s How China Escaped Shock Therapy (Routledge, 2021), but this might be beyond the pale for someone who has expressed contempt for market interventionists such as John Maynard Keynes.

The connections Thiel makes between economics and other factors are astute, as are the connections that Galbraith makes. Galbraith’s proposed policies require a high degree of social unity, which seems unlikely in the extremely polarized United States. Thiel’s scapegoating could generate this needed level of unity but the U.S. cannot win a war against China, Russia, or even Iran. The superior approach is a Thiel/Galbraith synthesis: dispense with the impotent saber-rattling and hostile stance toward the social safety net; instead direct wrath toward a largely parasitic and rent-extracting billionaire class, treat China as a powerful competitor, and concentrate on increasing domestic industrial capacity with an emphasis on the greatest threat to America (and mankind: climate change).

Thanks to you Patrick Lawrence, to you Haydar Khan, and to all at The Scrum who made it possible for this article to be here. No article could have been of more interest to me. Weird I’m on time for once; am considering a month after it came out…finding it “on time” enough! Half left to read tomorrow.