Twilight’s last gleaming: Can Americans learn to accept the notion of post-exceptionalism?

Among the fundamental conceits of the exceptionalist creed is that America is above the laws that govern all other nations. A leap of faith is required to end this fallacy, argues Patrick Lawrence

At four-thirty in the afternoon on Saturday, 4 April 2009, Barack Obama stood before a throng of correspondents in the Palais de la Musique et des Congrès, a high-Modernist convention centre on the Place de Bordeaux in Strasbourg. It was his 74th day as president. He had earlier attended his first G20 meeting, in London, and had just emerged from his first Nato summit, a two-day affair that featured sessions on both sides of the Franco-German border. The world was still intently curious as to who America’s first black president was and what, exactly, he stood for.

Confident, easeful, entirely in command, Obama spoke extemporaneously for several minutes. He spoke of “careful cooperation and collective action” within the Atlantic alliance. He noted “a sense of common purpose” among its leaders. He was there “to listen, to learn, and to lead”, Obama said, “because all of us have a responsibility to do our parts”.

Then came the questions. There was one about the global financial crisis Obama had walked into as soon as he walked into the White House. There was one about Nato troops in Afghanistan. Then came a question from the Washington correspondent of the Financial Times. It was a little long-winded and is reproduced in the transcript thus:

“In the context of all the multilateral activity this week – the G20, here at Nato – and your evident enthusiasm for multilateral frameworks, could I ask you whether you subscribe, as many of your predecessors have, to the school of American exceptionalism that sees America as uniquely qualified to lead the world, or do you have a slightly different philosophy? And if so, would you be able to elaborate on it?”

This is known in the trade as a softball, the kind of gently lobbed query that sets up a public figure to dilate safely and at length on a favoured theme. And so did Obama field it. “I believe in American exceptionalism,” the new president said spryly, “just as I suspect the Brits believe in British exceptionalism and the Greeks believe in Greek exceptionalism.”

Like an incoming tide flowing over rocks, the questions returned to troop counts, Nato contributions, and Albania’s accession to the alliance. No one seemed to take much note of either the FT man’s inquiry or Obama’s reply. And no one, not even America’s new president, seemed to grasp what had just happened to exceptionalism, that peculiarly awkward term with its peculiarly ideological load. Something broke at that moment. It was as if Obama had dropped a precious relic, some centuries-old crystal chalice, and no one present heard the noise when it shattered.

Obama’s conservative critics haunted him after that afternoon in Strasbourg. It was as if he had strayed beyond the fence posts defining what an American leader can and cannot say – and then hastened to return to the fold. “My entire career has been a testimony to American exceptionalism,” he once said. On another occasion – this time in a commencement address at West Point: “I believe in American exceptionalism with every fibre of my being.” He pursued the theme until the very end of his presidency.

None of this – the president’s critics, the president’s ripostes – did much good, if any, for the abiding notion of American exceptionalism, whichever of its numerous meanings one may subscribe to. Others may read the matter differently, but to me that afternoon in Strasbourg was a point of departure long in coming. However the question is addressed, it reiterates the same lapse, the same self-consciousness, the same self-doubt, the same collective anxiety long evident to anyone able to discern with detachment the sentiments common to many Americans.

Obama had it right that day in Strasbourg, of course, having settled on the only logical way at the matter. All nations are exceptional, but none, not even America, is exceptionally exceptional. Whatever Obama’s intent, he had stripped bare America’s customary claim to exceptionalist standing, exposing it at last as empty of all but the most mythical meanings. This was an immensely constructive thing to do.

To risk a generality, Americans had been an uncertain people – nervous, defensive, given to overcompensation for never-to-be-mentioned failures and weaknesses – for a long time before Obama spoke in Alsace. I trace this shared-by-many attribute to another April, this one 34 years earlier, that wrenchingly poignant season when Americans sat in frozen silence as news footage showed them helicopters hovering above the embassy in Saigon – the frenzy of a final retreat. For now, it is enough to note that Obama’s observation – a touch offhand and as simple as it was obvious – marked the moment Americans would have to begin rotating their gaze, in a gesture not short of historic for its import, if they were to do at all well in the new century. They would have to turn from a past decorated with many enchanting ornaments towards a future that has no ribbons or laurels for those who claim them by virtue of some providentially conferred right.

Obama left Americans with questions on the day I describe. They require us – and I think by design – to begin talking of what I will call post-exceptionalism. This was Obama’s true legacy, in my view. In the best of outcomes, we will learn to answer these questions in a new language, as the best answers will require. What will be the nature of a post-exceptionalist America? Who will these post-exceptionalist Americans be? What will remain of Americans once the belief that they are chosen is subtracted – as inevitably it will be. Can a post-exceptionalist America come to be? Given the chasm in their consciousness that must be crossed, will Americans accept another idea of themselves and of themselves among others? Or will they continue to pretend against all evidence that the chalice remains intact, unshattered, still to be held high above the heads of others atop our city on a hill?

It is common enough to locate the origins of America’s self-image in the thoughts of the earliest settlers coming across the Atlantic from England. It was John Winthrop, in his famous 1630 sermon, who gave us our hilltop city. Even in this seminal occasion we detect a claim – maybe the earliest – to exceptional status. But it is to the 18th and 19th centuries, as America made itself a nation, that we have to look for the grist of the exceptionalist notion. And instantly we find a confusion of meanings. To some it referred to the new nation’s revolutionary history, its institutions, and its democratic ideals. In its early years, the nation was also counted exceptional for its abundant land and resources.

New and evolving meanings attaching to the term have tumbled down the centuries ever since. And long has been the journey, exceptionalism having gone from observation to thought to article of faith, ideological imperative, a presumption of eternal success, and a claim to stand above the laws that govern all other nations.

WEB Du Bois, the great black historian and social critic, was among the first prominent critics of the notion that America and its people were in any way singular or in any way not subject to the turning of history’s wheel. He found the source of our modern idea of exceptionalism in the post-bellum decades leading up to the Spanish-American war. Two visions of the American future emerged after the civil war, Du Bois observed in Black Reconstruction in America: 1860-1880, his 1935 history of African-American contributions to the post-war period. In one of these renderings, America would at last achieve the democracy expressed in its founding ideals. The other pictured an industrial nation whose distinctions were its wealth and potency.

Democracy at home, empire abroad: when combined, these two versions of America’s destiny were to be something new under the sun, and this amalgam would make America history’s truly great exception. This was never more than an impossible dream. Du Bois considered it “the cant of exceptionalism”, to borrow a phrase from David Levering Lewis, Du Bois’s biographer. He saw it as a way to deflect the realities of the Great Depression.

It was a mere six years after Du Bois brought out his book when Henry Luce declared the 20th “the American century” in a noted Life magazine editorial. America was “the most powerful and vital nation in the world”, the publisher announced. It is “our duty and our opportunity to exert upon the world the full impact of our influence, for such purposes as we see fit and by such means as we see fit”. Maybe only the offspring of missionaries could write with such righteous confidence of dominance and purity of intent in combination. But Luce, without using the phrase, had neatly defined American exceptionalism in its 20th century rendering. And from his day to ours, that aspect of it we can consider religious has grown only more evident among its apostles.

Jimmy Carter caught the post-Vietnam mood perfectly (perfectly to a fault, as it turned out) when he delivered his “malaise” speech in mid-July 1979. Carter never used the wounding word. His title was “A Crisis of Confidence” and he made his point in vivid terms. “It is a crisis that strikes at the very heart and soul and spirit of our national will,” Carter explained on America’s television screens. He spoke of “the growing doubt about the meaning of our lives”. He spoke of “years filled with shock and tragedy”, and of “paralysis, stagnation, and drift”.

This was a presentation of remarkable candour by any measure. Carter told Americans, in so many words, that they could not count on any preordained destiny or that they were always assured of success because of who they were. “First of all, we must face the truth,” Carter said, “and then we can change our course.” This alone warrants considerable thought. Among the fundamental conceits of the exceptionalist creed is that America has always had it right and has no need to change anything. The national task is simply to carry on as it has from its beginning. Carter’s challenge to such assumptions could hardly have been bolder, and the public initially approved. As it turned out, however, Americans did not much want to hear their president confirm their post–Vietnam uncertainties so plainly.

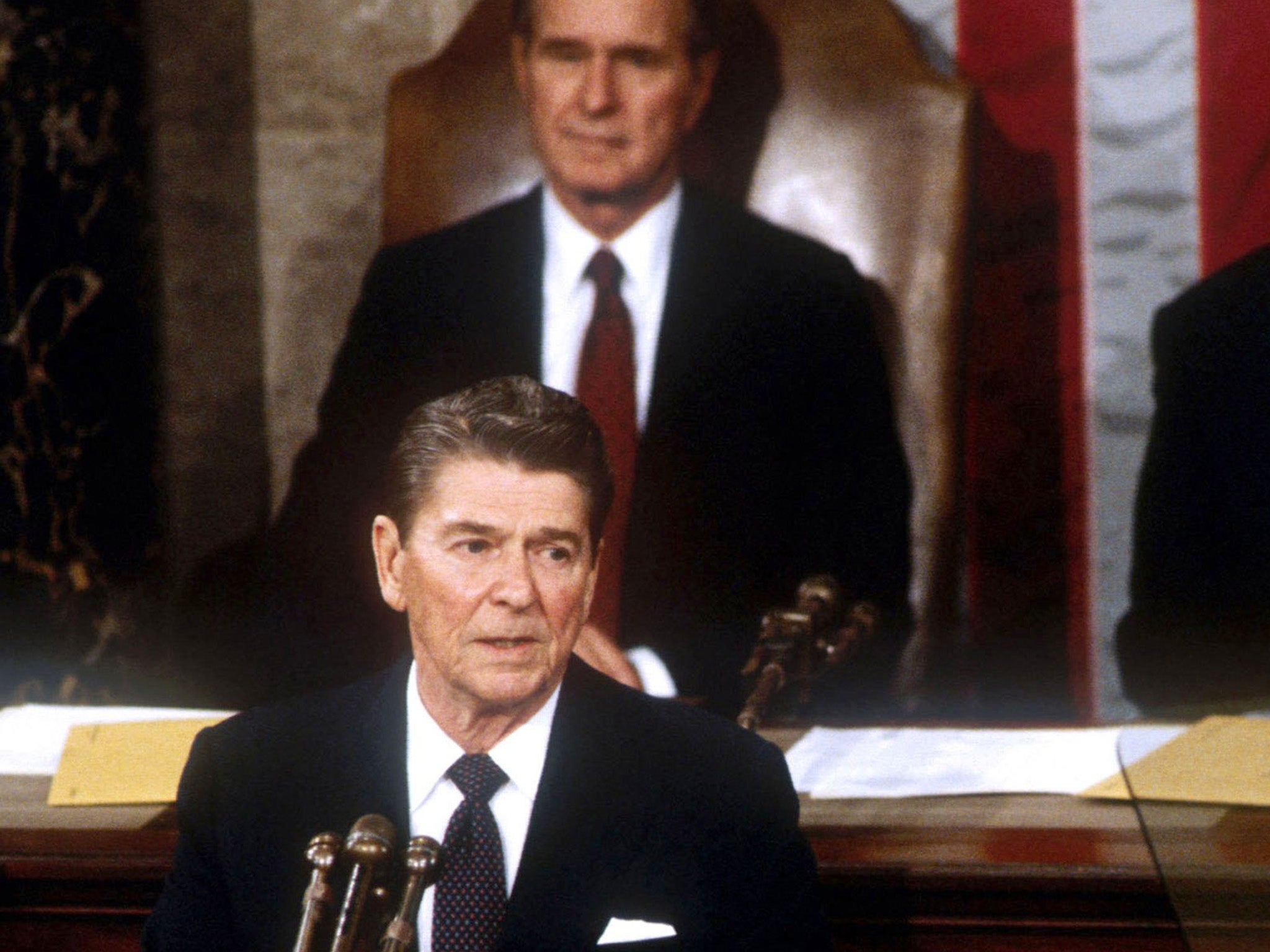

Ronald Reagan understood this. If American exceptionalism had not previously been a faith, Reagan set about making it one. As president he breathed extraordinary new life into the old credenda – notably in his famous references to Winthrop’s “city on a hill”, each one a misuse of the phrase. He quoted it coming and going – on the eve of his 1980 victory over Carter, in his farewell address nine years later, and on near-countless occasions in between.

I recall those years vividly, oddly enough because I was abroad during almost all of them. On each visit back there seemed to be more American flags in evidence – above front doors, on people’s lapels, in the rear windows of cars, in television advertisements. By the mid-1980s the nation seemed enraptured in a spell of hyper-patriotism Reagan had conjured up with the skill of the performer he never ceased to be. The stunningly rude conduct of American spectators at the 1984 Olympics in Los Angeles made plain to me that Reagan had set the nation on a path that was bound to deliver it into isolation and decline. “Patriotism” has ever since been a polite synonym for nationalism of a pernicious kind.

To me this turn in national sentiment reiterated what it was intended to refute: America was still the nervous nation Carter had described. It is difficult nonetheless to overstate the import of what Reagan did by way of his images and poses. He did not restore America’s confidence after Vietnam; in my estimation no American leader from Reagan’s day to ours has accomplished this.

Reagan’s feat was to persuade a nation, or at least most of the electorate, that it was all right to pretend: all was affect and imagery. As if to counter Carter’s very words, he licensed Americans to avoid facing the truth of defeat and failure and principle betrayed. He demonstrated in his words and demeanour that greatness could be acted out even after it was lost as spectacularly as it had been in Indochina. Beyond his face-off with “the evil empire”, “Star Wars”, “the magic of the marketplace”, and so on, Reagan’s importance lay in his intuitive grasp of social psychology. He understood: many Americans, enough to elect a president, prefer to feel and believe more than they like to think. It was “morning in America”, and all one had to do was have faith in the man who said so.

We still live, roughly speaking, with the version of exceptionalism Reagan crafted to evade the verities of our Vietnam debacle. This is an immense pity, the consequences of which are hardly calculable. Defeat is the mulch of renewal. Was this not Carter’s implicit point? Defeat gives the vanquished an occasion to reflect, to reimagine themselves, to pursue a new way forward. History offers numerous examples. The 20th century fates of Germany and Japan are of an order all their own, but they serve well enough to illustrate the point: after downfall comes regeneration.

Fail to “face the truth” – Carter’s well-chosen phrase – and one must count defeat evaded a lost opportunity of fateful magnitude. The defeat in Vietnam, to make this point another way, could have launched us into our post-exceptionalist era – which, I am convinced, was Carter’s intent in 1979 as much as it was Obama’s 30 years later.

Post-Carter and now post-Obama, we can speak of hard exceptionalism and a soft alternative. The hard variety derives from Reagan, who drew on Henry Luce’s do-what-we-want, where-we-want, how-we-want notion of American pre-eminence. It is subject neither to international law nor, when all the varnish is scraped away, ordinary standards of morality. Against this we find counterposed the more humane (if finally more cynical) version of exceptionalism put forward by Obama and many others on what passes, remarkably enough, for “the Left” in American politics.

Gone is the Reaganesque jingoism and the whiff of Old Testament righteousness characteristic of conservative renderings. Instead, we find “plain and humble people … coming together to shape their country’s course”, as Obama once put it. On the foreign policy side, this is a nation that admits its mistakes while leading the world by way of those partnerships Obama mentioned in Strasbourg. America’s conduct abroad must be rooted in the same humility characteristic of its people – the people ever busy shaping the nation’s course.

Taken together, these two versions of America as it looks in the mirror are nothing if not reiterations of the post-civil war binary Du Bois astutely identified – empire abroad and democracy at home.

Jake Sullivan, an adviser in the Obama administration and Hillary Clinton’s deputy chief of staff at State, voiced a view on the soft side in the January 2019 edition of The Atlantic. “This calls for rescuing the idea of American exceptionalism,” Sullivan wrote two years into the Trump presidency, “from both its chest-thumping proponents and its cynical critics, and renewing it for the present time.” He then unfurled “a case for a new American exceptionalism as the answer to Donald Trump’s America First – and as the basis for American leadership in the 21st century”.

Sullivan does not seem to understand. Exceptionalism is no longer an idea: it is a belief and cannot be resuscitated by way of rational thought no matter how acute the rational thinking. I question the efficacy of any foundational creed in need of a salvage job of the sort Sullivan proposes. This is not how religions – civil, in this case – work. Nonetheless, soft exceptionalism is now the frontline defence of the notion among Washington’s thinking elites. And we can count Sullivan’s essay its most thorough treatise to date.

Sullivan’s case is multiply flawed. Soft exceptionalism is finally little different from the hard kind, given the two meet at the horizon. They both rest on the old belief that, uniquely in human history, America manages to combine virtue and power without the former’s corruption by the latter. Hegemon or “benevolent hegemon” – a phrase from the triumphalist 1990s I have always found risibly preposterous – place America at the pinnacle of the global order, sequestered from others by dint of goodness and greatness in combination. Hard or soft, they both treat scores of coups, interventions, subterfuge operations, and countless other breaches of international law as deviations from the norm – even as more than a century’s evidence indicates these supposed irregularities have been the norm.

There is a point to be made here that I count more significant than any just listed. Whatever variety of exceptionalism anyone may endorse, it will not open us to the rich benefits to be derived from defeat or retreat; as we all know, exceptional America never lost anything and never will. This is one of the creed’s two essential purposes. On one hand it is a declaration of permanent victory. On the other it is an amulet to ward away the doubt and uncertainty that lie at the core of the American character.

Exceptionalism in any form, then, prevents us from seeing our past clearly and imagining a different kind of future. It amounts to a cage within which we choose to confine ourselves and wherein we learn nothing – the conceit being we have nothing to learn. We are the jailer and the jailed. And if the 21st century has one thing to tell us above any other, it is that we must turn the key, escape our narrow cell, and begin to think and live in ways our claim to exceptionalism has too long rendered inaccessible to us.

In the spring of 1932, Henri Bergson published his final book. He called it The Two Sources of Morality and Religion, “morality” to be taken here to mean a society’s ethos, how it lives. A quarter of a century had passed since the French thinker brought out his celebrated Creative Evolution. This last work amounts to an elaboration on the earlier volume’s themes.

Once again, Bergson takes up the binaries running through much of his work: “repose” and movement, the closed society and the open, the stable and the dynamic – the latter in each case driven by his famous élan vital, the impulse within us to create and evolve. As in the earlier work, Bergson posits the what-could-be against the what-is.

The distinguishing mark of The Two Sources is its exploration of the “how” of change – how a society advances from an established state to one newly realised. His answer is surprising. Progress is achieved not systematically but creatively. It does not occur as a result of careful bureaucratic planning, one measured step succeeding another. It entails, rather, “a forward thrust, a demand for movement”. This requires “at a certain epoch a sudden leap”. Bergson calls this a saltus, an abrupt breach resulting in transformation.

Here is an essential passage in the argument Bergson constructs:

“It is a leap forward, which can take place only if a society has decided to try the experiment; and the experiment will not be tried unless a society has allowed itself to be won over, or at least stirred. … It is no use maintaining that this leap forward does not imply a creative effort behind it, and that we do not have to do here with an invention comparable with that of the artist. That would be to forget that most great reforms appeared at first sight impracticable, as in fact they were.”

There are a couple of things to note in these lines as we consider the prospect of a post-exceptionalist America. One, ordinary Americans – a critical mass, let us say – must be open to making the required leap and to the measure of flux – an interim of instability, even – this implies. So must our political thinkers, scholars, and policy planners – altogether our intellectual class. Two, creative advances require creative individuals – in a phrase, imaginative leaders who can see beyond the closed circle of assumptions that any given society forms. So it is with dynamic leadership. What at first throws us because it appears to be wholly impractical is later on accepted as a new norm. American history, and that of many others, give us numerous examples.

Bergson’s thinking is of great use, it seems to me, in any effort to change course – to redirect American power. But he immediately faces us with questions, two more atop those already posed.

How given are Americans to the “forward movement” Bergson writes of? A good many appear eager for holistic change, a saltus of our own. For these many, it is a question not of repudiating national aspirations but of abandoning the mistaken course corrupt interpretations have set us upon. To return to Du Bois’s thesis, this constituency now understands that the exceptionalist notion of a virtuous empire and a thriving polity has proven disastrous. Dominance abroad must give way to democracy at home. Such a transformation would constitute a truly forward movement.

But America is now a house divided, to note the self-evident. Many of us appear to have lost touch with all that might pass for creative drives. There is much to suggest that seven decades of pre-eminence have left too many of our leaders incapable of anything that might pass as a reconstituted vision of the nation’s future. They persist, instead, in the long-bankrupted pursuit of democracy and empire – the old, impossible dream. They cling to illusions of moral clarity consolidated during the Reagan years and now proffered by such figures as John Bolton, until mid-September Trump’s astonishingly dangerous national security adviser. Their influence continues to keep us from changing anything about our ways of seeing and thinking – our “morality,” the ethos by which we live. Ours seems a closed society, in Bergson’s terminology. It is costly indeed to stray beyond the fence posts.

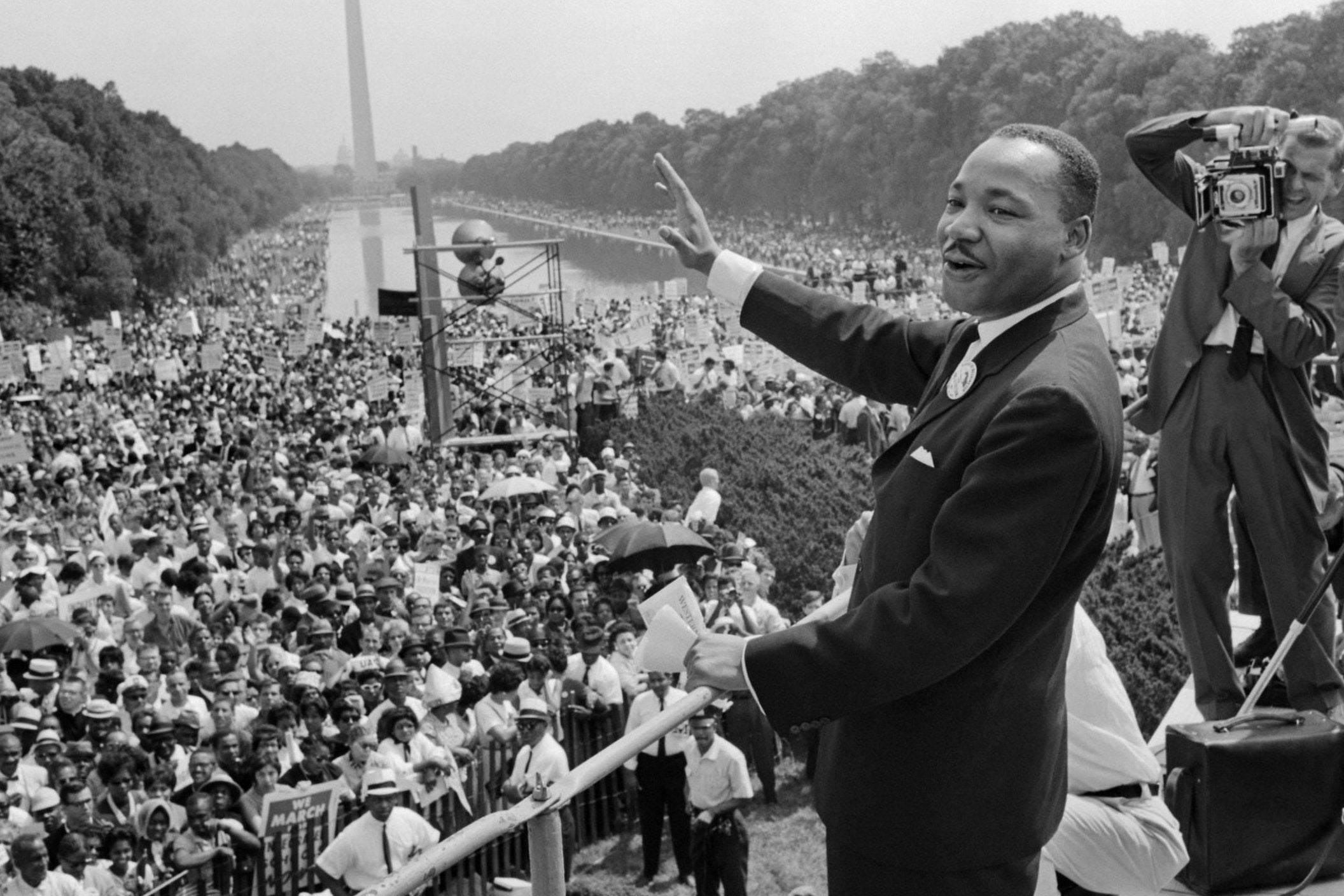

Whether America is any longer capable of authentic change depends in large measure on how we answer the other question Bergson imposes upon us. Do we Americans have the leaders to inspire us forward, to cut our moorings, to “win us over” to the condition of post-exceptionalism? Bergson’s thought as to the necessity of gifted leadership (a term he does not actually use) is especially pertinent in the American case. It is perfectly sensible to suggest, as many do, that a transformation in Americans’ understanding of themselves is beyond reach, or that a tremendous shock – a catastrophic defeat, a sustained depression – will be required to bring it about. But these are the replies one will always hear within the confines of a static political culture. They admit of no prospect of transcending the what-is. They leave no ground for imagining what a committed leader might accomplish. Anyone who doubts this potential should consider the tragic turn the nation took after the three assassinations of the 1960s – the two Kennedys and Martin Luther King Jr. They were leaders of the kind Bergson compares with artists. It would be difficult to overstate the impact their deaths have had on the nation’s direction.

For the moment we do not seem to have such leaders. But it is worthwhile considering figures such as Obama (or Carter, for that matter) with this question at one’s elbow. I do not wish to overfreight Obama’s appearance in Strasbourg very early in his first term, but in that fateful sentence concerning Americans, “Brits,” and Greeks lies a hint, surely, of a leader’s alternative vision of America’s way into the 21st century. An attempt was made, suggesting imminence. We are now face to face with the pity of Obama’s retreat. With it he deprived himself of all chance of greatness – and Americans of a chance to move beyond their state of “repose”. But we also find among us an incipient generation of leaders who stand squarely against our condition of inertia. Tulsi Gabbard, the vigorously anti-imperialist congresswoman from Hawaii, is but one example of this emergent cohort. The common theme is plain: to remake American democracy and to abandon imperial aspirations are two halves of the same project.

This is where we are now with regard to our exceptionalism. We stand at a crucial moment, and there is no place in it for pieties as to the “can do” of the American character. It is difficult to argue that we as a society are prepared for this. But it is nonetheless time – if, indeed, we are not already late – to make our leap into a post-exceptionalist awareness of ourselves and others. It is time to leave something large and defining behind. The only plausible alternative is failure – once again, among ourselves as well as among others.

There are sound reasons to assign our time this magnitude of importance. Abroad, the world tells us nearly in unison that the place the old American faith found in the 20th century is not open to it in the 21st. At home the intellectual confinements exceptionalist beliefs impose have debilitated us for decades. We are now greatly in need of new thinking in any number of political and social spheres, even as we deny ourselves permission to do any. Clever restorations of the sort Jake Sullivan urges will not do.

What does “post-exceptionalism” mean? How would it manifest? Who would post-exceptionalist Americans be? How would Americans understand themselves and account for themselves among others? Would anything be left were the mythologies to be scraped away?

I began with these questions. They have no simple answers. But there is a long tradition of dissent and dissenters in America –“exceptionalism’s exceptions,” as Levering Lewis termed them. Much of what is pushed to the margins in American history is by no means marginal – a point our best historians have made many times. In the supposedly far corners of our past we find paths to a future beyond exceptionalism. The lively anti-imperialist movement that arose in the 19th century’s last years is a relevant case in point.

Among my starting points when considering the idea of post-exceptionalism is an imperative that came to me after living and working many years abroad, primarily in Asia: parity between the west and non-west will be an inevitable feature of this century. To take but one example, one reads little in the American press about the network of alliances now forming among non-western nations in the middle-income category: between Russia and China, Russia and Iran, China and Iran, India and all of these. American exceptionalism, let us not forget, was born and raised during half a millennium of western pre-eminence (taking my date from da Gama’s arrival at Calicut in 1498). This era now draws to a close before our eyes. No one’s antiquated claim to exceptionalism can survive its passing.

As a corollary, the same point holds within the Atlantic world. Europe now struggles for a healthy distance from America after the suffocating embrace of the Cold War decades. If success so far proves limited, the direction is clear. One of the truths I learned when reporting in Indonesia during the first post-Suharto years, a time when various provinces were demanding autonomy, was that to stay together the Indonesian republic would have to come partially apart. The same will prove so of the west and all who identify as belonging to it. As in Indonesia, there is difference amid similarity, and both must be served.

It will be a post-exceptionalist American leadership that accepts these dramas with the thought and imagination needed to find opportunities – as against an almost fantastic variety of “threats” – in the soil of new landscapes. In the best of outcomes, nostalgia for lost pre-eminence, our post-war pursuit of totalised security – these will no longer interest post-exceptionalist American leaders. Theirs will be a nation braced to advance into a new time because it is confident of its competence to do so. It will be cognisant of the perspectives of others, a capacity Americans have heretofore found of little use. It will be game, in a word – aware of its past but never its prisoner. The language of dominance will give way to the language of parity. International law will be our law as it is everyone else’s.

And here we come to the essential motivation for us to make our leap – the sine qua non of it: it must first dawn on us that it is greatly, immeasurably to our advantage to attempt it. This truth has not yet come to us; no leader has led us to it. How little do most of us understand, in consequence, that to abandon our claims to exceptional status will first of all come as an immense unburdening and a relief from our long aloneness in the world?

All of what I have just noted in pencil sketch lies within our reach. None of it is a matter of law or mere policy. It comes to a question of will and of vision, of who we wish to be. But let us not make one of the very errors we would do best to leave behind: what Americans can do and what they will do are two different things. There is no certainty Americans will reach for any of what is available to them. To abandon our claims to exceptionalism is to give up our assumption of assured success. It requires us to accept the difference between destiny and possibility. One does not find abundant signs Americans are yet ready to do this – not among our leaders, in any case. There seems little awareness that the only alternative to the change of course Jimmy Carter favoured forty years ago this past summer is decline – decline not as a fate but as a choice, one made even as we do not know we are making it.

“Can America save itself?” Bernd Ulrich, a noted German commentator, wondered in Die Zeit not long ago. It is precisely our question as we look towards a post-exceptionalist idea of ourselves. This, indeed, was Ulrich’s unstated topic. “In principle, absolutely,” he replied to his own question. “But certainly not with gradual changes. In terms of global politics and history, it must get off the high horse it has so long ridden. It needs a moderate self-esteem, beyond superlatives and supremacy.”

A longer version of this essay appears in Raritan.