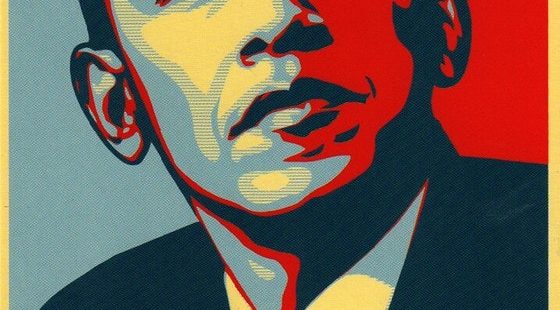

“The return of the blob.”

No hope. No change. Just Biden’s favorite Blobsters.

On Monday, President-elect Biden unveiled his national security team. The results may have come as a surprise to progressives who lied to themselves (and their readers) over much of the past year in their confident predictions that Biden would be pulled “left” on foreign policy questions.

If anything, Biden’s picks prove the truth of John Kenneth Galbraith’s observation made some two decades ago: “A major feature of our foreign policy [is] its institutional rigidity, which holds it on course even when it is visibly wrong.” The institutions that have contributed to this rigidity—governmental and nongovernmental alike—are almost without exception run by members-in-good-standing of the entrenched foreign policy establishment.

And so, far from picking a team that might break with the ossified bipartisan interventionist consensus of the past 30 years, Biden has surrounded himself with unrepentant and unreconstructed liberal interventionists who embrace the most dangerous illusions about America and our role in the world.

Biden’s picks for director of national intelligence, Avril Haines, national security advisor, Jake Sullivan, and secretary of state, Antony Blinken, are the very same personnel that, under Obama, oversaw needless, immoral and counterproductive American involvements in the Saudi war on Yemen, the overthrow of Muammar al–Gaddafi in Libya, the dangerous deterioration of relations with Russia, the world’s second largest nuclear power, the attempted illegal overthrow of Bashar al–Assad in Syria, and a drone war conducted with precious little oversight.

The mindset of the incoming group is well represented by a speech Tony Blinken gave at the hawkish Center for a New American Security back in 2015. Blinken was then serving as deputy secretary of state, and the Obama administration was ramping up its efforts to lay the foundation of a two-front cold war with Russia (via an irresponsible proxy war in Ukraine) and China (via the much talked about “pivot to Asia”).

“For me,” said Blinken, “the question is not and indeed its never been whether America is leading; the question is how we’re leading—by what means, and to what ends.” This is the credo of the bipartisan consensus: America must lead, irregardless of the domestic and international consequences. Blinken continued that in his view, “We must lead from a position of strength, with unrivaled military might, a dynamic economy, and the unmatched strength of our human resources.” Standard issue establishment boilerplate. Does it ever occur to these people that the twin pursuits of “unrivaled military might” and the fashioning of a “dynamic economy” here at home might be at cross-purposes?

In announcing his nomination to become the next secretary of state, TheNew York Times approvingly noted that engaging in “multilateral efforts to confront China” will be among Blinken’s top priorities. One wonders if that will be time well spent. After all, as the scholar Michael Lind has observed, “At some point, the perversity of stationing U.S. military forces in China’s major trading partners to protect them from a largely imaginary threat of Chinese invasion and occupation will be too obvious to be denied.”

There are shades of neoconservatism in Blinken’s thinking. In a 2019 op-ed co-written with the neocon ideologue Robert Kagan, Blinken endorsed a favorite idea of the late senator John McCain, that of forming a “league of democracies” to counter what is seen as the threat posed by what Blinken and Kagan described as China’s “techno-authoritarian model of governance.”

What they didn’t mention is that China, quite unlike the U.S., has all of one overseas military base (in Djibouti), while the U.S. has by some estimates 800 military bases in more than 70 countries. Still more, the U.S. is saddled with mutual defense treaties with no fewer than 69 countries—which, taken together, include fully one-quarter of the planet’s entire population. There is indeed a need for us to re-think our alliance strategy, but the formation of (yet another) American-led alliance isn’t one of them.

The Biden appointments have certainly cheered Washington’s well-compensated Blobsters, who dominate the think tank-academic-defense-industry nexus, i.e., the other side of the revolving door to government. Even the neocons are on board. The head of the rabidly Likudnik Foundation for the Defense of Democracies tweeted his approval of the picks, while the risible hack Jennifer Rubin gushed that the picks filled her “with hope and pride.”

In addition to the chorus of approval Biden’s picks elicited from the very worst people in Washington, the neoconservatives, what is also striking about the nominations is just how conventional they are. But perhaps that’s to be expected because the Blob is, in addition to being very dangerous, completely unimaginative: not exactly an inspiring combination.

Consider, for a moment a Foreign Affairs piece entitled “In Defense of the Blob” authored by three neocons, two of whom (Peter Feaver and Will Inboden) are veterans of the George W. Bush administration. According to them, there is no need to search for alternatives to the consensus: After all, “the foreign policy establishment is an American strength” that, they claim in the face of virtually no evidence, “learns from [mistakes] and changes course.”

Similarly, Samantha Power, the journalist-turned-liberal Blobster, recently took to the pages of Foreign Affairs with her own defense of Blob mentality. According to Power, before Trump all was well and good in the world. “For all the criticism directed at U.S. foreign policy in eras past,” she writes, “foreign leaders and publics largely retained respect for the United States’ willingness to undertake challenging endeavors and its ability to accomplish difficult tasks—a significant but underappreciated cornerstone of American power.”

Which challenging endeavors? Which foreign publics? She neglects to say.

Power continues: “The new president will have to grapple with the widespread view that in key domains, the United States… does not have the competence to be trusted.” Trust, of course, is a cornerstone of diplomatic engagement. Yet I personally find it jarring to hear this sort of thing come from Power, who gave one of the most dishonest performances I’ve witnessed during my time in Washington when she testified before the House Foreign Affairs Committee. Power denied any knowledge of Kiev’s problematic conduct (including its responsibility for any civilian casualties) during the war that was then engulfing Ukraine in 2015.

In any case, Power was thrilled by Biden’s nomination of her friend Blinken to the office to which she no doubt aspires. Her former colleague on Obama’s NSC, Tom Hartig, joined in, tweeting: “One big thing that jumps out from Pres-elect Biden’s early national security appointees: they are all incredibly kind people.”

And that may be so.

But oftentimes in the business of foreign affairs, it’s the people with the best of intentions who are prone to do the most damage.