The real story about Syria and Libya: Behind a new agreement with Moscow, and the insidious way the New York Times protects Hillary

A new accord with Moscow on Syria clears up little. And a new Times series on Clinton and Libya has a messy agenda

Hardly does the Syria accord announced jointly in Washington and Moscow last week clarify the swamp of complications, divided loyalties and treachery that have defined the crisis for years. It does not. We do not know yet even if the “cessation of hostilities” will hold, to say nothing of whether it will open any door to political negotiation and a settlement. It is fragile; the predictable interests—notably Turkey and Saudi Arabia, Washington’s principle allies—are already trying to tip the deal over.

But the doubters overdo it, in my view. They judge the agreement as if they were making book on it: No previous attempt to halt the violence has succeeded, so the odds are this one will collapse, too.

Shallow thinking—the kind one gets from the pack animals that staff our newspapers. You have to look carefully at this agreement and the circumstances that led to its conclusion last week. A lot has changed since the previous attempt at a ceasefire, in 2014, failed in less than a day. At close range, I see grounds for optimism—O.K., tempered, attenuated optimism. And I mean this two ways.

One, there is the question of motivation.

This accord has just two signatures on it—Washington’s and Moscow’s. That is a strength, not a weakness, as some commentators have suggested, for they are the parties to this conflict who will determine the outcome. When a Russian warplane flew its first bombing sortie over Syrian soil last September 30, this conflict was confirmed as a theater of great-power rivalry. And the Americans and Russians now have good reasons—very different reasons, of course—to make this agreement hold and go somewhere. They did not a matter of weeks ago.

Two, Syria now begins to take its place in post-Cold War history. It is a prominent place, and we should be clear about this, difficult as it always is to see one’s moment in historical context.

Remember the summer of 2008, when the Bush administration thoughtlessly encouraged Mikheil Saakashvili, the irresponsible Georgian who is now Kiev’s appointee in Odessa even as he flees international warrants on criminal charges, to provoke a confrontation with the Russians? I was in East Asia, my mind on other things, but I recall friends writing to say, “Don’t miss this: American power has just reached its limit.”

It had not, plainly, but the thought looks more credible now. Taking Ukraine and Syria together—and there are plenty of reasons to do so—they define an historical moment. We watch as American power and prerogative are turned decisively back.

The history of American foreign policy in the last century and the first years of this one is littered with failures, of course. But these two suggest a turn in the story. In the most specific terms, it looks as if we witness the passing of the “regime change” phenomenon. At the very least, Moscow has put Washington on notice that there will be no more of it without serious, open-ended resistance. Ukraine and Syria, after all, are two very sizable failures in this line.

Point of clarification. The U.S. has been in the business of covert coup operations the whole of the postwar era, and one seriously doubts the C.I.A., which operates ever more independently of civilian control, has plans to change its habits. The Clintonians coined “regime change” in the 1990s, when the coup function went from covert to overt. We were all then invited to partake of their liberal righteousness as they made destroying other governments—elected or otherwise, it never matters—an apple-pie aspect of what America does.

Already we find that the policy and the term sanitizing it, once a point to boast upon, subtly become a political liability. I will return to the thought later on.

*

Here is the text of the agreement Washington and Moscow announced jointly last week, putting it in effect last Friday at midnight. It is not complicated as these things go. There is provision for the “cessation of hostilities,” which is not (somehow) the same as a formal ceasefire. The clearest explanation of the current state of play is in the first sentence:

“The United States of America and the Russian Federation, as co-chairs of the International Syria Support Group … are fully determined to provide their strongest support to end the Syrian conflict and establish conditions for a successful Syrian-led political transition process, facilitated by the U.N.,…”

The sentence goes on to list various resolutions and communiqués pertinent to the present undertaking.

There are a couple of things worth noting.

One, the phrasing marks a large step in Washington’s reluctant and reluctantly acknowledged acceptance that working with Russia is not merely the best way to resolve the Syria crisis: It is the only way. Behind this, the Russians have a facility in Latakia monitoring the ceasefire, the Americans have one in Amman, and the two are in regular communication. This is something new.

I truly do not want to think about how many dead or displaced Syrians would not be dead or displaced had the Obama administration reached this point a year or so ago, when the Russians began to moot a blueprint for a Syrian settlement that looks very like the one to be taken up once the halt in hostilities is consolidated. Staffan de Mistura, the U.N. official who diligently stage-directed the agreement, expects talks to begin as early as March 25.

Once again, in failure we find success.

Two, by now you have surely noted what is not in the cited sentence, and you will not find it anywhere else in the accord, either. There is no mention of removing President Assad in Damascus as a precondition of political talks. This is huge: It makes official Washington’s surrender of its “regime change” ambitions in Syria, which were the very foundation of American policy from its (covert) entry into the Syrian conflict in 2012.

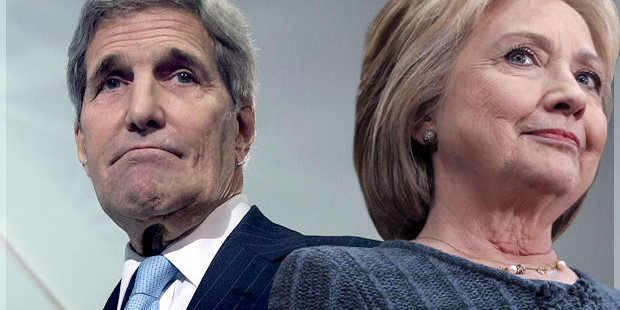

It has been good family fun to watch Secretary of State Kerry and his staff climb ever so gradually down from their reckless insistence on another Middle Eastern coup—a policy framework Hillary Clinton shaped during her time as secretary of state. It has been even more entertaining as the New York Times accommodated this unadmitted admission of stupidity and failure. We may read little or no more about it, but these past months are distinguished among the Times’ many say-it-without-saying-it interims.

Now it is on paper: Syria for Syrians, and they will determine Assad’s future as they determine their own.

Many responsibilities now fall to the Russians and Americans. Meet them and “Syria for Syrians” will not sound so angelic a thought. It will be essential to scrutinize and assign any failure in the weeks and months to come, because as many have already remarked, this is the best chance we have had to end the Syrian catastrophe since protest tipped into violence four years ago.

For the Russians, the tasks these:

* Moscow’s biggest responsibility is political. Directly or indirectly, amicably or coercively, it must keep the Assad government—which has accepted the accord but has not signed it—in line. This should not be difficult: As other commentators have observed, the cessation of hostilities is likely to serve Assad’s interest, not least because of dramatic gains on the ground the Syrian Arab Army made just prior to the agreement.

“The pause in fighting may have the unintended consequence of consolidating President Assad’s hold on power over Syria for at least the next few years,” David Sanger wrote in the Times last weekend. “It may also begin to freeze in place what already amounts to an informal partition of the country, even though the stated objective of the West is to keep the country whole.”

I do not know where “the next few years” comes from, given the intent of political talks now in the planning stage. And “an informal partition” seems to be another term for federalization, which may be no bad thing if the artificial creation known as Syria is to remain a unified nation.

The important point here is this: Russia has secured Damascus for the time being and now must make sure Assad does not act self-destructively. The ultimate goal is to avoid another Libya-like scene, wherein Assad is chased down a sewer pipe, gruesomely executed and the chaos that follows makes him look pretty good in retrospect (as Saddam Hussein came to look O.K. in the face of Bush II’s war and its consequences).

* More immediately, Russian warplanes will continue bombing Islamic State and al-Nusra targets—neither is covered in the accord—as well as other terrorist militias. They must be pinpoint careful not to give those opposed to the agreement and what political progress may follow any excuse for resuming hostilities. I do not see this as anything more than a logistical task well within the Russian Defense Ministry’s capabilities, but the stakes are rather high: The Saudis, in particular, are ready to pounce at the very slightest hint of an infraction on Russia’s part.

I see Russia staying with this. To an extent I have never found appealing, post-Soviet Russian leaders are eager to please the West—the sotted Yeltsin was craven in this regard—and in Putin’s case this comes over as a desire to achieve some kind of parity or partnership status with the Americans. I do not know why leaders in the non-West think this continues to matter as much as it once did. In Russia’s case there is nearly two centuries of history behind this cast of mind, not much of it very good.