“The Last Pragmatist.”

After Jim Baker, the triumphalists.

Peter Baker and Susan Glasser. The Man Who Ran Washington: The Life and Times of James A. Baker III. Doubleday. 720 pages.

It did seem for a while that James Addison Baker III was in some danger of being either forgotten by a younger generation for whom all political history begins and ends with the names “Barack” and “Hillary,” or simply relegated to the annals of political skullduggery for his role in securing (others, perhaps with justification, would say stealing) the presidential election for George W. Bush in 2000—a role for which he was memorialized by the great Tom Wilkinson in the HBO docudrama “Recount.” Whether you agree or disagree with Baker’s politics, given the breadth of the man’s time at (or damn close to) the very pinnacle of power in Washington, this seems a disservice to the man and to history.

In The Man Who Ran Washington: The Life and Times of James A. Baker III, Susan Glasser and Peter Baker rescue Jim Baker from what otherwise could have been a very unearned obscurity. Peter Baker, a Washington correspondent for TheNew York Times, and Glasser, a staff writer for The New Yorker, bring us back to—if not the good ol’ days of Washington politics—certainly a time that compares pretty favorably to our own. That’s a low bar to clear, to be sure, but they do us a service by recalling a time, not too far distant, when inveterate dealmakers such as Jim Baker, House Speaker Tip O’Neill, and power brokers such as Ways and Means Chairman Dan Rostenkowski and Senate Majority Leader George Mitchell could forge important—if necessarily imperfect—deals on issues such as social security, tax reform and (some) matters of national security. Yet Baker and Glasser don’t, as many contemporary pop historians such as the unctuous Jon Meacham do, waste the reader’s time with ahistorical exhortations about a sun-lit past that never was: Baker and Glasser have too much respect for the reader’s intelligence (and too much intelligence themselves) to extol the virtues of a period that gave us, among other things, Watergate and Iran–Contra.

Today, aside from his role as longtime Bush family consigliere, Baker is primarily known as one of the principal architects of post–Cold War Europe. But what’s interesting is that Baker, who, over the course of 12 years went from White House chief of staff to treasury secretary to secretary of state and back again to chief of staff, possessed no formal training or experience in economic or foreign affairs. Baker was foremost a political animal with an unerring instinct for survival. His main qualification was his decades-long friendship with a Texas transplant named George Herbert Walker Bush. Proving the truth of the old adage, It’s not what you know, it’s who you know, Baker parlayed his ties with Bush with such skill that by 1976, only a year after arriving in Washington, he was running Gerald Ford’s reelection campaign. By 1980, he had arguably eclipsed Bush, first as campaign manager, and soon after, as chief of staff to Ronald Reagan.

Baker and Glasser’s account is first and foremost a study of power: how Baker got it, wielded it and, ultimately, lost it. And, perhaps not surprisingly, some of Baker’s handiwork looks less stellar with the passage of time: Baker was instrumental in bringing Alan Greenspan in to replace Paul Volcker at the Fed and in bringing Dick Cheney from the House leadership to the Pentagon. The Cheney appointment gave the neocons and hardliners within the administration a powerful ally. In the course of the book it becomes clear that Dan Quayle’s vice-presidency was a kind of a dry run for how the neocons would operate during the next Republican administration under Vice–President Cheney. Quayle, his chief of staff Bill Kristol, along with the ever-conniving Bob Gates, who was then serving as deputy national security adviser, were able to feed their own bogus intelligence regarding the Soviet Union to the president with the goal of undercutting Baker. Fortunately, Bush, who, unlike his son, was a former intelligence chief and seasoned foreign policy hand, usually dismissed what was obviously politicized intelligence.

The author’s account of Baker’s early life, rise to prominence, and service in the Reagan administration is judicious. It is when we arrive at the chapters on Baker’s tenure as secretary of state, 1989–92, that we get a sense that this leg of the story will be shaped, and not for the better, by the authors’ ideological biases.

True believers, alas.

While I cannot say where Peter Baker falls on the ideological spectrum, it would not be unreasonable, given a survey of herwork in recent years, that Susan Glasser would have fitted in well with the old New Republic liberal-neocon crowd that ran that magazine under Martin Peretz and the absurd Leon Wieseltier. If she isn’t a full blown neocon, she’s at least neocon-adjacent, a fellow traveler of militarists, interventionists, and Cold War enthusiasts. And so, when we get to the penultimate section of this otherwise estimable book, which concentrates on Baker’s years at State, the authors find fault with, or at least evince a kind of distain for, the things Bush and Baker got right—while failing to take them to task for the things they got wrong.

The reason for this is straightforward enough: Jim Baker was a dealmaker and pragmatist, and the authors seem to be ardent believers in the idea that the U.S. has the moral right and duty to shape the world as it sees fit. In other words, they are idealists in the same way Samantha Power or Hillary Clinton or Robert Kagan claim to be. For writers and thinkers such as Peter Baker and Susan Glasser, the imperative among high officials is “to do something” and sort out (if ever) the consequences later. The imperative for someone like Jim Baker was to avoid doing “stupid shit,” as Barack Obama once famously advised. And to George Bush’s and Jim Baker’s great credit, they often did.

But caution and restraint aren’t qualities that will win you praise from establishment fixtures like Glasser and Baker, and so the duo single out Baker and Bush for their marked preference for maintaining stability, as against the heavy-handed tactics and triumphalist rhetoric that followed their time in office. The author and journalist Robert Wright might even detect a level of cognitive empathy on their part. And so, Bush and Baker displayed a mature prudence when commenting on the events in Tiananmen Square, the fall of the Berlin Wall, and the dissolution of the Soviet Union. Their promises to Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev not to extend NATO “one inch eastward,” and Baker’s clear-eyed assessment of U.S. interests in the Balkans (“We don’t have a dog in this fight”) show levels of prudential realism that have not been seen since they left office. This grates on Glasser and Baker, who note that Bush’s and Baker’s “mutual instinct skewed toward stability.” This is doubtlessly meant as criticism.

And yet, in light of the events of the past 30 years, I believe this reflects rather well on them. Writing in his diary on November 8, 1989, Bush notes, “I keep hearing the critics saying we’re not doing enough on Eastern Europe…if we mishandle it, get way out looking like an American project, you invite crackdown [which] could result in bloodshed.” Baker is described as watching “what was happening in Berlin and Prague and Warsaw with a sober eye, wondering how to harness the revolutionary energies now unleashed and channel them to a secure outcome with a minimum of damage.” In light of the disastrous results of recent American interventions in Europe, particularly with regard to the role we played in fanning the flames of ethnic sectarianism in Ukraine in 2013–14, the authors shouldn’t be so quick to dismiss the wisdom of Bush’s and Baker’s pragmatism.

So they mostly dealt with the world pragmatically and avoided doing stupid shit.

Mostly.

Bush’s customary caution abandoned him when it came to dealing with Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait. Today, and for understandable reasons, the first Gulf War compares favorably to the sequel. But it, too, much like the war Bush’s son needlessly started in 2003, was a war of choice, one that set the stage for a series of foreign interventions that future presidents—from Clinton to Bush to Obama—would wage. George H.W.’s Iraq war, also like the sequel, was based on false intelligence. According to the historian Jean Edward Smith, “at no time did either the Central Intelligence Agency or the Defense Intelligence Agency believe it probable that Saddam would invade Saudi Arabia.” And, like the sequel, the administration undertook a deeply misleading public relations campaign to rile the public. In a precursor to Condi Rice’s infamous “mushroom cloud” declaration, Bush’s national security adviser, Brent Scowcroft, appeared on ABC’s This Week and said it could be “a matter of months” before Saddam Hussein had nuclear weapons.

The war, over in a matter of 72 hours, pushed Bush’s approval ratings to 89 percent, the highest ever recorded by Gallup. And yet. The postwar decision to station American troops in Saudi Arabia, which was never really threatened by Saddam in the first place, set the stage for worse to come: In August 1996, Osama bin Laden issued his ‘“Declaration of War Against the Americans Occupying the Land of the Two Holy Places.”

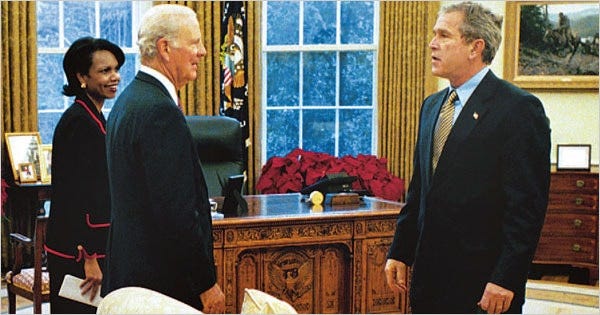

The final chapters of The Man Who Ran Washington are taken up with Baker’s lucrative post-government career, principally (and somewhat controversially) as a rainmaker for the Carlyle Group, and his involvement in the 2000 Florida recount debacle. And it wasn’t long before Baker would be called to government service again. According to the authors, George W. Bush wanted Baker to replace Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld in 2005. Baker declined but was pressed into service as co-chair (along with former Indiana congressman Lee Hamilton) of the Iraq Study Group, whose recommendations were quickly cast aside.

At one point, Baker and Glasser observe that during G.H.W. Bush’s presidency, Baker and Bush had “elevated prudence and pragmatism as the cardinal American virtues.” To which one must respond: “If only.” In summing up, Baker is said to have been “driven by a desire to bring stability and order, not to shake things up. He never saw America’s commitment to freedom as a mission statement to change a world that was not ready to change.” But Jim Baker’s way of seeing things did not, alas, become the template that would guide future American presidents and diplomats. What a pity.