“The great reset, part 2.”

An attempted corporate coup.

Second of two parts.

In their Reset primer, Klaus Schwab and Thierry Malleret consider what the post–Covid world might look like at various levels of civilization. While the authors frequently inject their vague and utopian hopes and wishes for the post-pandemic world, they acknowledge the possibility that humanity could be headed for a dystopian nightmare. But they consider this bleak scenario only briefly, in all likelihood because it is inconvenient to their case. What specifically do the authors see or hope to see arising as a consequence of the pandemic? What alternatives do they ignore? Let us dig deeper into the Reset text.

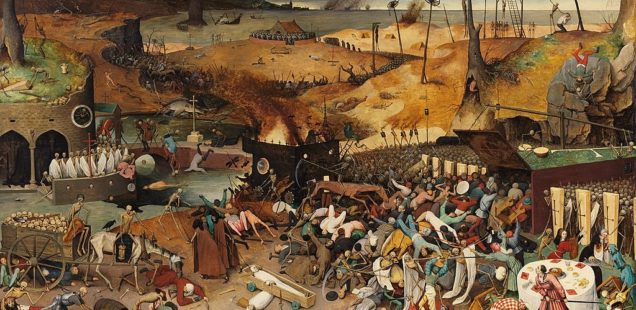

In the introductory section of Covid–19: The Great Reset, the authors point out that pandemics have impacted human civilizations throughout history. From the Byzantine Empire to the Aztecs, pandemics have shaped and, in some cases, destroyed entire societies and cultures. A particularly salient example of this is the effect of the Black Plague on Europe: It diminished the church as a political force, helped end the feudal system, and assisted in the birth of the Enlightenment. Of course, as the authors point out, there has never been a pandemic with the reach that Covid–19 has: This pandemic is unique for having broken out in a world that is a hyperconnected complex system with an accelerated pace facilitated by digital technology. “Behavior is intrinsically difficult to model,” they write, “due to the dependencies, competitions, relationships, or other types of interactions between their parts or between a given system and its environment.”After this introduction, the authors go on to make claims and predictions that cover many aspects of society, ranging from economics and geopolitics to technology.

The economic predictions touch on labor, capital, growth, distribution of wealth, state power, and social safety nets. Traditionally, pandemics have, in the authors’ words, led to “gains in power to the detriment of capital,” but they also point out that history may be no guide here as automation and digitization may prevent this rebalancing. With respect to growth, Schwab and Malleret make the case that a resumption to normal is probably not in the cards, as the economic fallout of Covid–19 will fatally wound the service-economy sectors that dominate the developed nations and will accelerate the already existing trend of labor replacement in the form of AI and robotics.

The authors express a mixture of concern and hope about this transformation. On one hand, many jobs could be supplanted by this automation revolution. On the other, productivity gains from such a paradigm shift could improve the quality of life for many if the gains are distributed fairly. With regard to distribution of wealth, another point made in the book is that “Covid–19 has exacerbated pre-existing conditions of inequality wherever and whenever it strikes.”

It is on this point that the Davos duo makes two bold assertions with respect to the future of wealth distribution and neoliberalism in general: 1) “the post-pandemic period will usher in a period of massive wealth redistribution, from the rich to the poor and from capital to labor,” and 2) “Covid–19 is likely to sound the death knell of neoliberalism.” Schwab and Malleret go on to claim that another future trend seems to be that of enhanced state power and a rewriting of social contracts. They argue that such trends will include expansion of social insurance, healthcare, and enhanced protection for workers, gig workers in particular.

The authors devote a lot of ink to geopolitical analyses. First, they predict that the pandemic will halt and even reverse globalization. They acknowledge that economist Dani Rodrik’s “globalization trilemma” thesis (you can have only have two of the following three: economic globalization, political democracy, and a nation-state) has been validated by Brexit and the rise of Donald Trump. Nationalism and protectionism will only accelerate due to Covid–19 and will result in a change in the “nuclear reactor” core of globalization: global supply chains. Countries will shorten or relocalize supply chains due to a need for risk reduction and political pressure. Malleret and Schwab predict that the end result of this process will be pockets of regional self-sufficiency, such as a strengthened free-trade consortium among the three nations that compose North America.

The second geopolitical topic that Covid–19: The Great Reset touches upon, if briefly, is global governance, meaning cooperation among nations to address common problems. The authors bemoan the breakdown in international cooperation as evidenced by national actions during the pandemic and predict that without some functional multilateral institutions, humanity will fail to address collective-action problems such as climate change.

The next geopolitical topic addressed by The Great Reset’s authors is that of rising tensions between the United States and China. Trade and national security frictions predated Covid–19, but the pandemic has accelerated the trend. The authors present three different viewpoints as to the outcome of this struggle in the Covid–19 context:

⁋ The first perspective is that China prevails over the U.S.

⁋ The opposite perspective is that the U.S. has come out on top. While wounded and declining, it still has massive cultural influence worldwide, its universities still draw worldwide talent, and the dollar remains the planet’s dominant currency, though America’s exorbitant privilege may be coming to an end.

⁋ The last perspective on this matter is that both countries have been permanently diminished, a consequence of their large scale, and smaller countries such as South Korea and Israel have had superior Covid–19 responses.

The last geopolitical topic discussed is the fate of “fragile and failing states.” The writers predict that commodity-dependent nations, poor nations, and politically weak nations will be hit hardest, and some nations could be pushed over a cliff. As a result, the world could see a massive rise in social unrest and refugee numbers.

Technology is a major focus of the macro section of The Great Reset. One of the authors (Schwab) has even written a book, The Fourth Industrial Revolution, focused solely on an impending revolution delivered by new technology and digitization. As with other current trends, the authors argue that Covid–19 will accelerate this new paradigm, specifically digital tech and automation. Due to lockdowns and confinement, consumers have been forced to rely heavily on digital applications and services, ranging from video conferencing to meal delivery. If social distancing is continued, the authors predict that reliance on these digital features may become permanent.

Also, as a consequence of infection fears, automation, in the form of robots, machine learning, and AI, will be heavily used to reduce health risks to humans. The authors next discuss the utilization of digital contact tracing and tracking to combat Covid–19. They observe that in many non–Western nations (China and South Korea are but two of many), this tracing was done without popular consent but achieved great results in managing the crisis, while such measures proved ineffective when they relied on voluntary adoption.

A medley of delusions.

What is to be said of the authors’ analyses? Their claims are mostly a medley of naïvete, contradiction, and outright delusion that lacks empirical validity. From economics to geopolitics, the Davosians repeatedly swing and largely miss.

With respect to wealth redistribution, the authors have consulted the wrong crystal ball, in my view: To take one simple metric of many, 10 men have accumulated $400 billion in additional wealth over the course of the pandemic and a political war is being fought in the U.S. over awarding a meager, means-tested check of $1,400 to qualifying Americans. Further, the authors have already expressed skepticism that the balance of power in our political economy will shift toward labor, so this is quite the contradiction. The claim about the impending doom of neoliberalism seems like a blatant falsehood, given Schwab defines stakeholder capitalism in neoliberal terms (“private corporations as trustees of society”).

A strengthening of the social safety net? This is wishful thinking if we take the U.S. as the canary in the coal mine. Prospects there are dim for such a reworking of the social contract. Millions have lost their health care, social insurance has expanded temporarily only after fierce political battles, gig workers in California recently lost a battle to be classified as employees, and gig workers across the nation may face the same threat. Further, Schwab and Malleret have a curious stance on Modern Monetary Theory, given they repeatedly advocate increased social assistance, health care, and social safety nets in general. The authors’ swipe is as follows:

The idea is appealing and realizable, but it contains a major issue of social expectations and political control: once citizens realize that money can be found on a “magic money tree,” elected politicians will be under fierce and relentless public pressure to create more and more, which is where the issue of inflation kicks in.

This is a misunderstanding of MMT, as its advocates are not magic money printers but supporters of full employment and price stability.

The geopolitical analysis is similarly flawed, as the U.S.-on-top scenario looks highly unlikely. This appears evident when one considers, for example, the demonstrated uselessness of the U.S. military in the face of Covid–19, the incompetent domestic response to this crisis, and the revelation of societal deficiencies, chief among them the absence of universal health care. Covid–19, to put the point simply, has devastated America’s image and altogether its standing in the community of nations.

What of the authors’ views on technology? More automation and digitization could lead to improvement in the lives of humanity but only if the productivity gains are distributed equitably, not hoarded by billionaire oligarchs. Could the result be dystopian, humanity’s every action is surveilled? Noted technology critics Shoshanna Zuboff and Evgeny Morozov get nods in the text, as they have both written of how the new digital world could lead humanity into disaster. Schwab acknowledges such concerns but ultimately dismisses these fears and insists that “the genie of tech surveillance will not be put back into the bottle.”

Perhaps tech surveillance is inevitable, but is this force unable to be governed and controlled? As Russian president Vladimir Putin said during a speech delivered to the World Economic Forum on January 27th:

Where is the line between a successful global business, in-demand services and consolidation of big data – and attempts to harshly and unilaterally govern society, replace legitimate democratic institutions, restrict one’s natural right to decide for themselves how to live, what to choose, what stance to express freely?

That is yet to be settled.

Who will be in charge?

Is the Reset a grand plan to enslave mankind? If I were being charitable, I would argue that the Resetters are naïve and merely hope—that most treacherous of the virtues—that the pandemic will somehow lead to “a more inclusive, resilient, and sustainable world.” But the Resetters are never specific as to how to achieve this state, other than by alluding to nebulous metrics and their equally nebulous “stakeholder capitalism.”

If I were not being charitable, I would argue that the Reset is merely the endgame of neoliberalism: a coup by corporations to supplant national sovereignty, somehow delivered by use of “stakeholder” capitalism and the ESG metric. The recent social media cancellation of former president Donald Trump is certainly a demonstration of private corporations serving as private trustees of society. A subtle hint as to intentions may have been revealed in Schwab’s earlier TIME magazine swipe at state capitalism:

But while state capitalism may be a good fit for one stage of development, it, too, should gradually evolve into something closer to a stakeholder model, lest it succumb to corruption from within.

This is a strange accusation, as it appears economic systems such as those of the U.S. are far closer than, say, China’s to succumbing to “corruption from within.” Economist James Galbraith has critiqued the current U.S. model as follows:

But without public planning, who is in charge? Lobbyists who represent the private planning of the great corporations. The public interest ceases to exist, and the public sector becomes nothing more than a trough at which private interests come to feed.

If the Reset is an attempted corporate coup, then Davos Man may be in for quite a shock. While a U.S. president may have been neutered by private corporations, the “China wins” scenario is looking more likely by the day: China is now expected to take the position of world’s largest economy by 2028, due in part to its response to the pandemic. Will other nations view China’s superior response to Covid–19 and attempt to mimic/learn from its state capitalist approach? Some U.S. advocates have been arguing for such an approach for years. Perhaps the Davosians would be wise to heed the words of Rabbi Hillel the Elder:

He who refuses to learn deserves extinction.

Professor Hayder Khan is a globally recognized mathematician of Bakhtiari descent. His incisive commentaries on a range of political, social, and economic questions are published widely.