“The great reset.”

Neoliberalism 2.0.

First of two parts.

There are rumblings among the Right and Libertarian factions of Western politics about a horrific plan that Davos Man intends to unleash upon mankind: The Great Reset! While Western conservatives and libertarians depict this as some sort of globalist attempt to take advantage of the disruption caused by the Covid–19 pandemic to impose a global, eco-socialist system of governance, this assessment is incomplete. At bottom, the Great Reset is the expression of a movement based on greenwashing, the fetishization of digital technology, and a neoliberal conceptual nucleus: a corporate structural “reform” called stakeholder capitalism.

Let us be wary.

If one scratches the surface of the Reset movement one can see why it should be viewed with skepticism and caution. It has many questionable boosters. Credibility is not strong when one’s movement is composed of such figures as Tony Blair, famous for foolishly lending British support to the 2003 Iraq war, or corporations such as Nestlé, notorious for taking worldwide advantage of lax tax laws and, further back in history, its disgraceful exploitation of mothers in developing nations in what is known infamously as “the baby formula scandal.” Indeed, the danger here is that corporations are hurtling towards a complete usurpation of national sovereignty, a global corporate coup intended not to impose a global Green New Deal but to maintain the neoliberal order.

The Reset crowd’s roots in Davos are not to be overlooked. Two prominent apostles of the movement, economists Klaus Schwab and Thierry Malleret, have a strong Davosian pedigree. Schwab founded the World Economic Forum in Davos 40 years ago. He is a former member of the steering committee of the Bilderberg Group, an organization dedicated to defending “free” market Western capitalism, and helped create the concept of stakeholder capitalism. Malleret is a former investment banker and founded/headed the Global Risk Network at the World Economic Forum.

To add further fuel to the skepticism fire, TIME recently partnered with the WEF and interviewed a number of Reset advocates, ranging from Doug McMillon, the CEO of Wal–Mart, a company notorious for its poor treatment of employees, to Kristalina Georgieva, the current director of the International Monetary Fund, an organization notorious for inflicting austerity and privatization programs upon nation after nation as conditions for needed multilateral financial assistance. The founders of this movement, Schwab and Malleret, claim in their book, Covid–19: The Great Reset, that this movement is “an attempt to identify and shed light on the changes ahead, and to make a modest contribution in terms of delineating what their more desirable and sustainable form might resemble.”

Schwab just recently published another of his promotional works in this line, Stakeholder Capitalism: A Global Economy that Works for Progress, People and Planet, which completes the picture—at least for now. His stakeholder capitalism is effectively the Reset’s “operating system.” After a preliminary examination of this concept, I will continue with a deeper exploration of the Reset movement by way of the Schwab–Malleret volume, which can be read as the Reset’s primer. It was published in Zurich by ISBN Agentur Schweiz on July 9, 2020.

It’s the market, stupid.

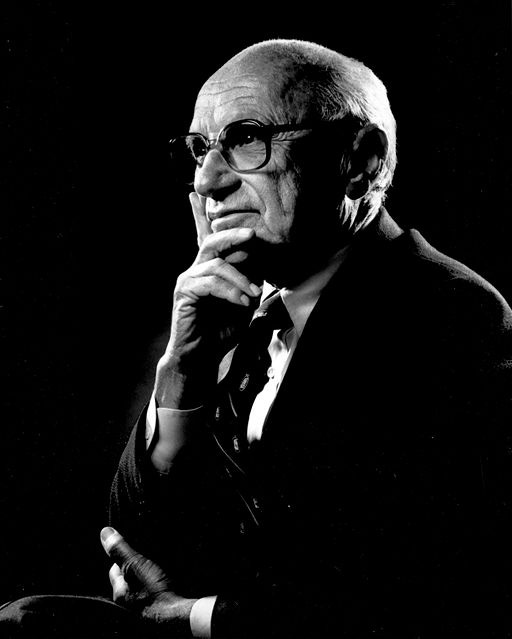

What is stakeholder capitalism? The term is now in common usage and the thumbnail definition is widely familiar, but let us consider its etymology. In its original meaning, stakeholder capitalism was Schwab’s proposed rival to Libertarian economist Milton Friedman’s concept of shareholder capitalism, a mode of capitalism wherein firms’ principal focus is maximizing profits for shareholders. This concept has effectively defined Western capitalism for the past four decades. As Schwab defined his alternative in a December 2019 essay for TIME:

“Stakeholder capitalism,” a model I first proposed a half-century ago, positions private corporations as trustees of society, and is clearly the best response to today’s social and environmental challenges [bold emphasis mine].

Schwab argues that the short-term perspective of shareholder capitalism is not sustainable for environmental and societal reasons and proposes that companies, in addition to shareholders, should include the interests of employees, customers, suppliers, local communities, and altogether society. As Schwab explains his alternative, he created the Davos-based WEF in 1971 “to help business and political leaders implement it.”

How does Schwab propose that this transformation take place? He advocates for companies to implement a new metric, ESG, to supplement traditional financial metrics: ESG measures the impact of business investment on the environment, society, and governance. Schwab claims that the “big four” accounting firms, led by Brian Moynihan, a Bank of America CEO, are in the process of developing this new industry standard, so the details are not yet clear. BlackRock, an investment firm with its $7 trillion under management, is piling onto the emergent ESG trend, claiming it “will double ESG investments in just five years.”

What should one make of these proposals?

For one thing, is this not a case of the fox guarding the hen house? Having entities such as the Bank of America create this new standard does not bode well for proposed reforms, especially given BoA’s lengthy history of chicanery. For another, making private corporations “trustees of society” is a highly pernicious notion fraught with dangers. It seems to contradict the very idea of national sovereignty and amounts to a stealth way of making the market the arbiter of our polities, a very neoliberal concept. Philip Mirowski, the noted philosopher and a critic of neoliberalism, offered a usefully pithy explanation of the logic of this perspective in a 2018 American Affairs article:

“The market” is an information processor, and the most efficient one possible—more efficient than any government or any single human ever could be. Truth can only be validated by the market.

This depiction of shareholder capitalism as a replacement for stakeholder capitalism is utopian in the extreme. Let us consider why.

According to the Davos Manifesto, published on the World Economic Forum website,

The purpose of a company is to engage all its stakeholders in shared and sustained value creation. In creating such value, a company serves not only its shareholders, but all its stakeholders—employees, customers, suppliers, local communities and society at large. The best way to understand and harmonize the divergent interests of all stakeholders is through a shared commitment to policies and decisions that strengthen the long-term prosperity of a company.

In other words, enhancing corporate profits is the fundamental objective of shareholder capitalism.

How this transformation will occur is another question. It is hard to see corporations voluntarily switching to a stakeholder model after being accustomed to forty years of rapacious shareholder capitalism. What non-corporate entity could possibly force corporations to transform? Governments come to mind as they have, in the past, acted as shapers and regulators of capitalism.

There is the prospect, however likely or unlikely, that corporations will eventually be persuaded that shareholder capitalism is ultimately beneficial to their bottom lines—in effect a new profit-maximization strategy with the added benefit of preserving the social order—and enter in enthusiastically. BlackRock appears to suggest that this shift may in time gain adherents, although the outlook must remain uncertain for now. And it is otherwise hard to see corporations voluntarily surrendering power.

Schwab nonetheless (and very ironically) makes the familiar claim we have come to call TINA since Margaret Thatcher made the phrase familiar—“there is no alternative”—and specifically dismisses state capitalism as a rival: “But while state capitalism may be a good fit for one stage of development, it, too, should gradually evolve into something closer to a stakeholder model, lest it succumb to corruption from within.” At bottom, it is important to note, Schwab is an ideologue straight from the neoliberal mold; he merely exchanges his quasi-religious beliefs for Thatcher’s and Reagan’s and Friedman’s. Here lies danger, in my view.

It is an extraordinary moment to advance this assertion, I must say, given China is currently weathering the Covid–19 storm quite well, while the U.S. and Western Europe struggle. But the dismissal of state capitalism is not the only error Schwab makes, nor is this the only occasion he displays a flippant disregard for alternatives. It certainly appears that the underlying operating principle of the Reset, stakeholder capitalism, is highly flawed and naïve, as an exploration of the Schwab–Malleret book will show.

Professor Hayder Khan is a globally recognized mathematician of Bakhtiari descent. His incisive commentaries on a range of political, social, and economic questions are published widely. This is his first contribution to The Scrum. Part 2 of this essay will follow shortly.