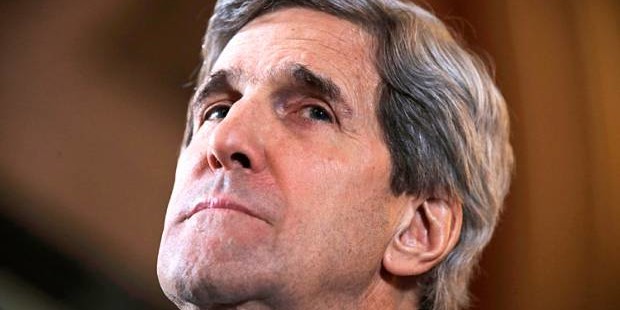

Someone teach John Kerry about history!

There’s a reason why Putin makes Kerry and the president look clownish: He understands the history others forget

Many Americans flinch from the latest turn in the Ukraine crisis now that Vladimir Putin has taken control of it. It was the same in Syria last autumn, you will recall. The Western powers whip themselves into a dither, and the Russian president then makes some simple, galvanizing move that puts everything on a different course.

In Syria, Putin and Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov jumped on an offer Secretary of State John Kerry made but never intended to: Within two days of Kerry’s much-noted press conference in London last autumn, Moscow had Bashar al-Assad surrendering his chemical weapons stockpile. The U.S. threat of a missile strike melted, and Putin had wrested the initiative in the Syria crisis from Washington’s grip.

Same again now in Ukraine. Just as the Obama administration and its European allies reached high decibels last weekend, Putin telephoned Obama in Riyadh and said approximately, “My people need to talk to your people now.” Kerry and Lavrov have been negotiating ever since, the American declaring that there is no solution in Ukraine but a political solution.

Some readers will think I glorify the Russian leader and denigrate the Americans as if on autopilot. This is not it. Putin is a gifted statesman: I stand by this observation. He brings an understanding of history to his foreign relations. And in his dealings with Washington he exposes the very old American habit of refusing history any place in the understanding of anything — which is to say the habit of making nearly every mistake it is possible to make. This is why I like watching Putin.

Now it is worth watching the Kerry-Lavrov talks with this thought in mind. Many things will be on the table: NATO’s eastward thrust, a federalist reinvention in Ukraine. In my view, the true topic will be one Washington has danced around for months. This is spheres of influence. Putin’s question all along has been simple: What do you Americans and Europeans think of them? Sooner or later those who have traded in “anti-Soviet” for “anti-Russia” without saying so will have to reply.

What should anyone think of spheres of influence, then? As often suggested in this space, best to begin with the history.

Spheres of influence are extensions of control beyond a given polity’s natural or declared borders. They can be formally declared or informal, aggressive or defensive.

The first thing to know is that in one form or another spheres of influence have been around as long as there have been human communities. Second, among the primary tasks of our time is to outgrow them. The third thing to know is that we have not yet done so.

Anyone who knows much about Chinese history can see the tributary system developed in the dynastic era as a textbook case of the phenomenon. This puts claims to a sphere of influence in the context of a political order back several millennia. Rome and Carthage later fought the Punic Wars over claims to influence in the Mediterranean.

Closer to our time, we have the Monroe Doctrine of 1823, when the young American republic declared itself master of the hemisphere. In 1885, the European powers met in Berlin and drew lines on maps so as to share out Africa among themselves.

The Berlin Conference is ordinarily said to be the quintessential example of the spheres-of-influence model in operation. Point taken, but I disagree with it.

The Cold War took the construct to its perverse extreme. I see no argument here. The planet itself was divided in two, forcibly in a lot of cases. This is why the Non-Aligned Movement had to be discredited. It is why Cold War Washington detested social democratic leaders such as Mossadegh. Everyone knew they were not Communist threats. The problem was they took no interest in East-West enmities — which is to say they refused to define themselves in the terms the American sphere insisted upon.

The Cold War will go down (eventually, I am certain of it) as an ugly scar the modern world inflicted upon itself out of no necessity. It behooves us to push past it by recognizing that spheres of influence are a crude, spent technology. Any core definition of the post–Cold War era has to include the thought that nations, cultures and societies will at last be allowed to self-define, self-identify and self-determine.