PATRICK LAWRENCE: Voting in a De-Facto Military State

Between Biden and Trump, U.S. voters have no alternative to our anxious empire’s lawless conduct abroad.

What are we in for on the foreign policy side come Nov. 3? Whoever wins this election, Joe Biden or Donald Trump, the answers before us are grim. For those who vote, the choice lies between a mentally impaired restorationist and a paralyzed captive of what some of us call the Deep State.

Think about this. The illiberal liberals, the only kind there are now, advertise Nov. 3 as the most decisive election in generations. This assertion is questionable even in the domestic context, but that is another conversation. As to the direction of U.S. foreign policy, there is no question: Between Biden and Trump, we are at bottom offered no alternative to our anxious empire’s conduct abroad.

Lawlessness, war and more war, destructive interventions in the name of righteous humanitarianism: We have no one but ourselves to blame for what will confront us in the four years to come. The divisive, nonsensical distractions of identity politics, “intersectionalism,” and all such narcissistic preoccupations carry a cost: No word is spoken among “progressives” about America’s imperial adventures. The lives of our countless victims abroad do not matter. The structures of power remain unchallenged.

This election is indeed of great significance, in my view. Given the absolute absence of any check on Washington’s projection of hegemonic power, known politely as “global leadership,” it will force a question upon us it is long past time to pose: Do Americans live under a de facto military government?

Tenuous Civilian Control of Pentagon

Anyone who thinks this suggestion is extreme should consider how tenuous civilian control of the Pentagon has been for many years. The defense industries bought Capitol Hill long ago — this is documented fact, however seldom acknowledged. The military-industrial complex’s power over the executive is just as real but less defined, and it has been especially apparent since Trump began his presidential campaign in 2015.

Foreign policy took up several important planks in Trump’s platform, readers may recall. He campaigned promising to reduce the military’s presence abroad, end our wars of adventure, ease NATO into the history books, and make a constructive relationship with Russia out of the unnecessary hostilities Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton, his secretary of state, left behind. These positions won him votes.

They won him enemies, too. A bevy of top national security officials and retired generals published open letters in The New York Times calling Trump a threat to national security. Michael Hayden, a retired general and former CIA director, suggested in February 2016 that the military would refuse to follow orders if Trump were elected and pursued his campaign promises.

Foiled Incumbent

Unsurprisingly, we have seen virtually no progress toward Trump’s objectives since he took office in January 2017. The Pentagon and the national security apparatus have ignored, circumvented, or otherwise subverted his orders to withdraw troops from foreign theaters, notably Syria and now Germany. Relations with Russia have dramatically worsened. NATO still pretends it has a function in the post–Soviet era.

These failures have three causes.

One, Trump is surrounded by people vigorously, ideologically opposed to his foreign policy goals, chief among them John Bolton, briefly his national security adviser, and Secretary of State Mike Pompeo. The only way to explain these appointments is to assume they were forced upon him. Trump, after all, doesn’t refer to the State Department as “the Deep State Department” for no reason. He is telling us something about his circumstances.

Two, Trump has proven impossibly erratic, saying one thing and doing another or doing one thing and later on saying another. This reflects his ignorance of the policymaking process and his near-complete lack of an intellectual framework through which to judge events and formulate strategies to sustain his objectives. Dealmaking in the fashion of a New York real estate developer simply doesn’t do it.

Three, Trump is far too conscious of his image. This prompts him to cave when the Pentagon or the spooks defy or circumvent him. In spring 2017, when the military contradicted his early efforts to deescalate in Syria, Trump entered his “my generals, my military” phase, saying he granted the Pentagon “total authorization” to act as it saw fit. With after-the-fact capitulations such as this, Trump has made himself a pushover for the hawks and Deep Staters who surround him.

There are a couple of things working in Trump’s favor. He’s to be credited for sticking with his original policy goals, even if they lie around him in ruins at this point. A second term might give him a chance to begin cleaning house and installing people who reflect his objectives.

In July Trump nominated Douglas MacGregor, a retired Army colonel, to replace loyalist Richard Grenell as ambassador to Berlin. MacGregor, like Grenell, is entirely on Trump’s page: He favors a reduced military footprint in the Middle East, a peace deal with the North Koreans and altogether a foreign policy to replace what now amounts to a military policy. A severe critic of NATO’s advance toward Russia’s borders, McGregor called the alliance a “zombie” in remarks made public last year.

But let us avoid mistaken judgments. First of all, a Situation Room stuffed to the rafters with Doug MacGregors is unlikely to bring the hamstringing of our 45th president to an end should Trump win a second term. The Deep State is also broad, and it has been both for a long time. Second, when Trump took office a few of us argued that he was a peculiar messenger but held out the promise of a renovated foreign policy. I was among the erring. After three and some years, I don’t think Trump has the grounding or consistency to get any such thing done. Washington is simply too much for him.

More of the same under a second Trump term is my call — a muddled White House at odds with itself, no worthwhile shift in policy permissible. Russian President Vladimir Putin recently offered a pithy take on Trump and his people, as recounted by Pepe Escobar, the peripatetic free-lancer for Asia Times: “Negotiating with Team Trump is like playing chess with a pigeon: The demented bird walks all over the chessboard, shits indiscriminately, knocks over pieces, declares victory, then runs away.”

I do not know the veracity of Escobar’s account, but it will make four more messy, dangerous years if this is anything like what we have to look forward to should Trump carry the vote a few months from now. Through all the fog, “his generals” will remain “totally authorized.”

Biden & Renewed Interventionism

There will be no such fog should Biden win in November, no ambiguity in his foreign policy plans. Biden promises a straight-ahead return to the policies that prevailed under Obama and Obama’s predecessors: a reclamation of “global leadership,” a renewed emphasis on interventions we justify, per usual, by casting ourselves as humanity’s archangels.

The wars and occupations will grind on, the extravagant Pentagon budgets will remain, the reigning Russophobia will remain. Biden is already well on board with the emergent Sinophobia.

The thought of a Biden presidency reminds me of the succession that followed the death of Leonid Brezhnev as the Soviet leader in 1982. The befuddled Yuri Andropov, who succeeded him, was a fill-in who came straight from the taxidermist and lasted 15 months. Biden is our Andropov. The take-home here: Those around Biden are the ones to watch, as they will have disproportionate power over policy. This will be a replay of the George W. Bush administration, to strike another comparison.

Team Biden’s foreign policy advisers are vast in number. Foreign Policy counts more than 2,000 of them, organized into 20 working groups covering specific issues — arms control, defense, intelligence, humanitarian missions, and so on —and geographies: Europe, the Middle East, East Asia. These people come from consultancies, think tanks, the State Department, academia. There is a heavy layer of Obama administration holdovers and, of course, Pentagon bureaucrats, some quite senior.

It is those to whom these groups report who count. Biden’s inner circle appears to include Jake Sullivan (Obama loyalist, apostle of American exceptionalism), Antony Blinken (Obama man, Russophobe), Susan Rice (warmonger, Russophobe, liar in public), Samantha Power (the humanitarian interventionists’ Joan of Arc), Nicolas Burns (State vet, “global leadership” hack), and Michele Flournoy (Pentagon careerist, hawk). These are joined, let us not forget, by the scores of anti–Trump Republican warmongers who have recently colonized the Democratic Party.

There are a threat and two certainties here. This election could end up opening the way for the U.S. eventually to become in fact what it has long been in effect — a one-party state. The foreign policy consensus the Biden camp now represents could solidify to the consistency of granite. This should frighten all of us — more, in the long run, than the Trump regime’s evident and many ineptitudes.

As to certainties, a Biden regime would force us back to an interim that began in response to the 2001 attacks and now ranks among the most disastrous foreign policy failures of the past 70 years, up there with the Vietnam War years. In addition, this will be an administration more thoroughly wedded to the military than Trump’s first term has proven. At least with Trump there was contention, bureaucratic warfare, infighting, objection. There will be none between the Biden White House and the Pentagon.

Is there somebody to vote for on Nov. 3? Is any vote a vote for generals?

like your picture choices

White House Military Bravado

The Dark Control of the USA

Trump alone, isolated, powerless

White House an empty stage

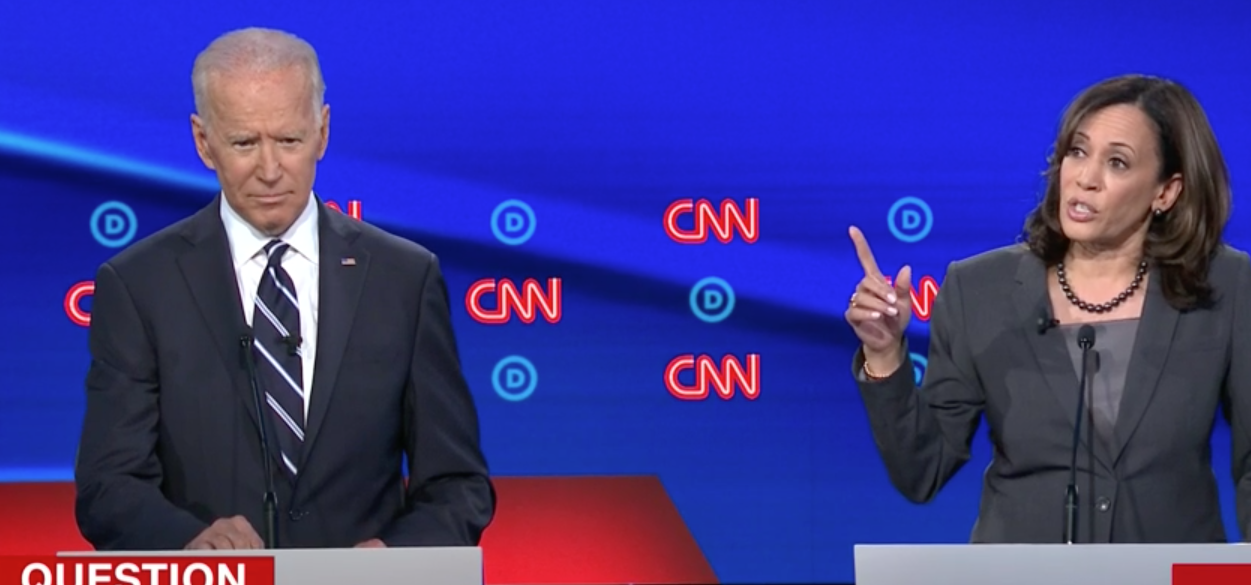

CNN and media photo op

DNC – the new vapid party