PATRICK LAWRENCE: It Was Kim That Walked Away

There are two sides to the story about why the second North Korea peace summit fell apart last week, writes Patrick Lawrence.

The abrupt and unexpected failure of the second Trump–Kim summit last week raises many questions. Let’s get one out of the way before addressing the others: No, the collapse of talks between President Donald Trump and Kim Jong-un, the North Korean leader, does not scuttle the most promising chance for peace on the Korean Peninsula since the 1953 signing of the armistice ending the Korean War. There is more to come. This was plain within hours of the summit’s end.

At this point it’s still difficult to discern even what transpired between the two leaders. The U.S. and North Korean accounts of the proceedings in Hanoi are widely at variance on key points. With history in view, it is very likely that the North Korean version comes closer to the truth than what the Trump administration is putting out and what the U.S. press is dutifully reporting.

Trump and U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo hold news conference after summit on Feb. 28, 2019, in Hanoi.(White House Photo by Joyce N. Boghosian)

By Trump’s account, Kim agreed to dismantle his most important nuclear production facility, at Yongbyon, roughly 60 miles north of Pyongyang. In exchange, Kim asked for all sanctions now in force against North Korea—some passed at the UN, others imposed by Washington alone—to be lifted.

Here is Trump talking to correspondents after the bust-up Thursday morning:

“Basically, they wanted the sanctions lifted in their entirety, and we couldn’t do that. They were willing to de-nuke a large portion of the areas that we wanted, but we couldn’t give up all the sanctions for that…. They wanted sanctions lifted but they weren’t willing to do an area we wanted.”

The “large portion” Trump mentioned is Yongbyon: There is no dispute about this. Pyongyang has shut down the reactor at Yongbyon twice in the past, in 1994 and in 2007. In 2008 Kim Jong-il, the reigning Kim’s father, ordered the cooling tower at Yongbyon demolished—a televised event many readers will remember. The site was reactivated in succeeding years following a series of multi-sided talks that went nowhere.

Kangson Facility

The “area we wanted” appears to refer to an alleged nuclear facility at Kangson, also near the North Korean capital. What the North actually does at Kangson has never been verified, but it was one of a number of sites the U.S. side also insisted Pyongyang close.

Translation of the U.S. version of events in Hanoi: Kim offered us only one item on our list while demanding we give him everything he wanted. Who could possibly agree to such a deal?

North Korean officials tell a different story. After Trump offered his post-summit description of events, the North’s foreign minister, Ri Yong-ho, gave his own press conference; a rarity among North Korean officials. Kim had agreed to shutter the North’s main nuclear facility, by Ri’s account, if the U.S. consented to lift only the five sets of sanctions imposed by the U.N. Security Council in 2016 and 2017.

Unlike restrictions on weapons and nuclear-related equipment, these covered entire export sectors, including minerals, metals, coal, agriculture and seafood. These, Ri said, were the measures that directly hurt the lives and livelihoods of ordinary North Koreans. Layer upon layer of other sanctions would remain in effect.

What’s Wrong?

Translation of the North Korean position in Hanoi: We will take a considerable step toward denuclearization providing you take one of corresponding magnitude. Now the question changes: What exactly is wrong with such a deal?

You have to go back to Trump’s early months in office to understand what appears to have transpired in Hanoi. The administration’s initial position was simple but ridiculous: The North had to completely disarm before Washington would even begin talks.

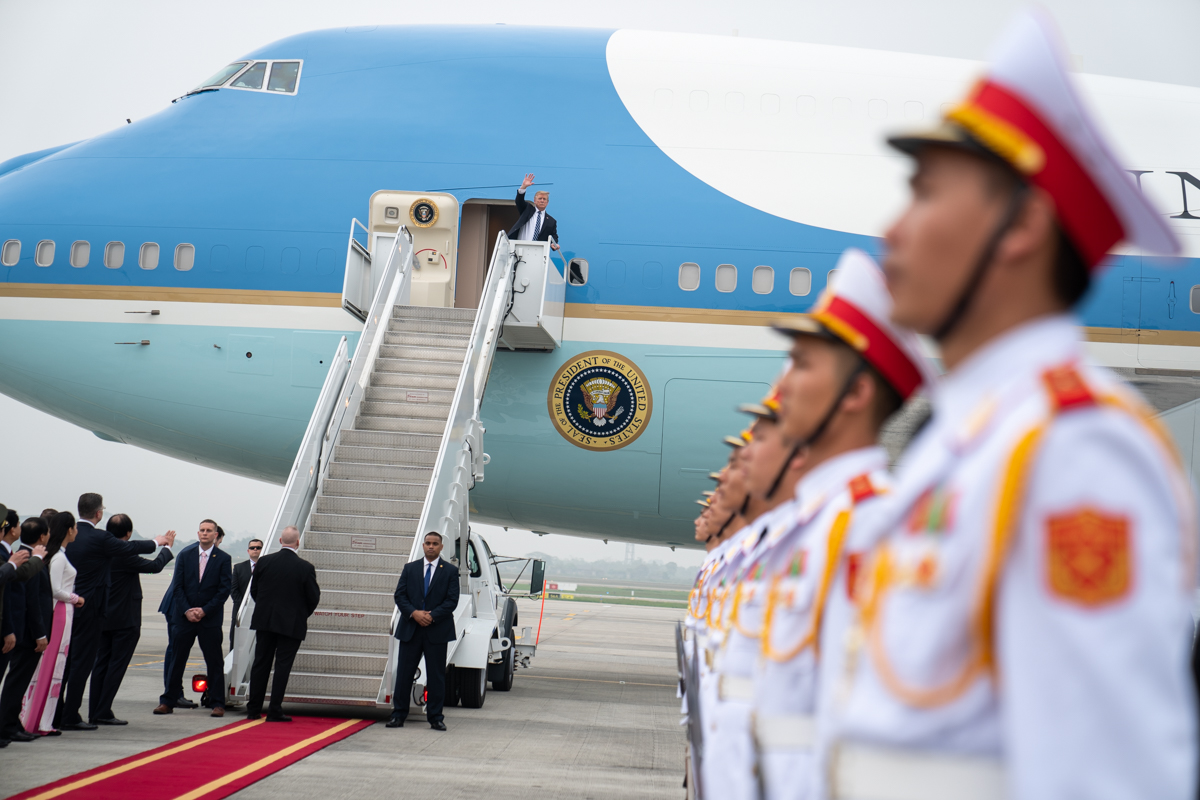

Trump leaving second summit with Kim Jong Un, Feb. 28, 2019, at Noi Bai International Airport in Hanoi. (White House Photo by Shealah Craighead)

Only when the absurdity of this maximalist demand became too obvious to sustain—”give us everything we will negotiate before we negotiate”—did the Trump administration alter its demands, if reluctantly and slightly.

Moon Jae-in, South Korea’s president, countered this as soon as Trump agreed last year to meet Kim, as they did in Singapore last June. The way ahead was “action for action,” in Moon’s phrase. Pyongyang’s term for the same thing is “corresponding measures.” Elsewhere the concept is called “sequencing.” Whatever one calls it, a gradual, step-by-step process is the only logical way forward after nearly seven decades of mutual distrust.

Trump’s Refusal

In effect, Kim proposed a sequenced approach when he met Trump last week. And in effect, Trump refused it. It is no wonder John Bolton, Trump’s national security adviser and the administration’s hyper-hawk on North Korea, has been assuring like-minded colleagues not to fret about the Trump-Kim summits because they are guaranteed to fail.

“This kind of opportunity may never come again,” Ri, the North’s foreign minister, said at his late-night press conference. This is not where the odds lie.

First, Moon Jae-in pledged to help mediate between the North and the U.S. as soon as the Hanoi summit collapsed. And it has been clear since Moon was elected South Korea’s president in May 2017 that control of the agenda on the Korean Peninsula has gradually passed from the U.S. to Seoul and those working with it, notably China and Russia.

Second, Moon enjoys a trustful rapport with Kim. And the latter is unquestionably serious about shifting the North’s priorities from nuclear capability to economic development. Kim wants a deal, in short.

The primary danger to future advances toward a lasting settlement in Northeast Asia lies in Washington. It has been the spoiler on the Korean question before, let us not forget. In the early 2000s, the U.S. never delivered two light-water reactors it had promised the North in exchange for its cessation of its nuclear program. After Yongbyon was shuttered in 2007, the U.S. failed to supply promised shipments of heating fuel, citing “an understanding between the parties” about which neither China nor Russia, who were also signatories to the agreement, had ever heard.

This time around, there is little question that Bolton and other hawks in the Trump administration intend to block progress as long as they can. They have just succeeded in scuttling Moon’s long-gestating plans to develop a series of cross-border economic projects. The South Korean leader had hoped that a planned communiqué to be issued at the summit’s end in Hanoi would have opened the way for these ventures to proceed. Trump and Kim never signed it.

“We had to walk away,” Trump said at his press conference in the Vietnamese capital. It is more likely that Kim is the one who walked away first.

“It occurs to us that there may not be a need to continue,” Choe Son-hui, Kim’s vice-foreign minister,said later. “We’re doing a lot of thinking.” It is difficult to blame Pyongyang for this, given the outcome in Hanoi.