“Pacific dénouements.”

We’re bombing badly in China.

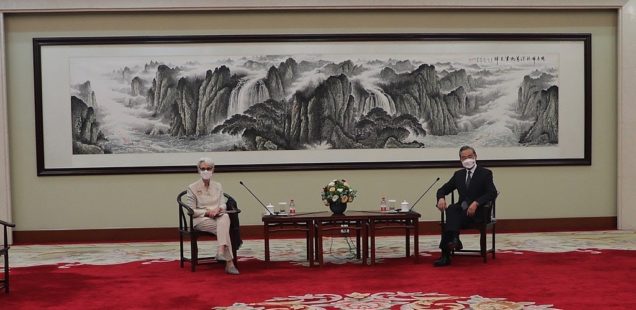

You did not read much about Wendy Sherman’s disastrous official visit last week to Tianjin, where the deputy secretary of state held talks with Xie Feng, her counterpart as vice-foreign minister, and met—key distinction here—Wang Yi, China’s foreign minister and Sherman’s senior in rank. I saw a Reuters item, here; The New York Times dipped in as cursorily as it could and then went back to Eighth Avenue and more congenial topics—the latest alleged horror from that rampaging putschist, the Idi Amin of American politics, Donald Trump, for instance. The Times piece is here.

No, you didn’t read much about Sherman’s undertakings in China because her visit was… disastrous. American diplomats, as readers of the Times know well, do not suffer disasters when they go forth to represent our republic. When diplomatic disasters occur they do not qualify as news fit to print.

Sherman has done well enough as a second-rate technocrat in the past three Democratic administrations—Clinton’s, Obama’s, and now Biden’s—and second rate does it among our foreign policy cliques these days. She advised Clinton on North Korea at a key moment in the mid–1990s and got some briefly promising diplomacy done with Kim Jong-il—a notch on her holster. She helped lead talks on the accord governing Iran’s nuclear programs, 2013–15, another mark in her favor.

But she has an unfortunate knack for blowing it badly when attempting grand pronouncements purporting to wisdom, these things said. When commenting on Japan’s fraught, highly complex relationships with South Korea and China some years ago, Sherman remarked, “The Koreans and Chinese have quarreled with Tokyo over so-called comfort women from World War II. There are disagreements about the content of history books and even the names given to various bodies of water…. Of course, nationalist feelings can still be exploited, and it’s not hard for a political leader anywhere to earn cheap applause by vilifying a former enemy.”

Subtle, nuanced, historically informed. “Clank” is the sound this made in Seoul and Beijing.

The comment I recall most readily is one Sherman made when testifying in the Senate as to the about-to-begin negotiations with Iran, in 2013. Of those who were shortly to sit across the mahogany table, this: “We know that deception is part of the DNA.”

Just right, American diplomacy at it most enlightened—a national-character argument about those with whom one wishes to achieve something worthy. After reading that I considered it halfway to a miracle FM Mohammad Javad Zarif got anything done with her—or tried, indeed. The forbearance of others is a blessing we Americans ought to appreciate more than we do.

I am not much interested in Sherman, in truth. The aspect of this bureaucrat I find salient at this moment is that she evidently has no experience in Asia or among Asians, has never lived there, never studied its history, has no understanding of its cultures, political traditions, or what the world looks like from any Asian perspective (of which there are many). And there she is, Antony Blinken’s No. 2, off to meet senior Chinese officials and advance the single most significant relationship Washington has and will have in this century.

Wendy Sherman may be a t.i.p., to borrow D.H. Lawrence’s clever mot, a temporarily important person, but her dramatic bomb-out in Tianjin is not a temporarily important development in trans–Pacific relations. It marks a very significant step toward a point of no return in Sino–American ties. We ought not miss this significance. It is why The Times did not much want to write about it. (And I must say the rug under which the once-and-no-more newspaper of record sweeps awkward matters is getting awfully lumpy.)

Sherman’s visit to Tianjin marked the third occasion on which Biden regime officials encountered the Chinese leadership. There was the Blinken debacle in Anchorage last spring, a stunningly inept display on our secretary of state’s part. All our top diplomat could think of to do was shake his finger at the Chinese about Xinjiang, Hong Kong, human rights, press freedoms, Taiwan, and other matters we have exaggerated, misrepresented, and weaponized—all of which (including Taiwan) are internal affairs, whether we Americans like the thought or not. There was, de rigueur when Blinken is holding forth, “the rules-based international order,” mustn’t forget this.

Ka–boom. Blinken lit the fuse, and it exploded across the table, where the Chinese listened and—good on them—sat up and then gave as good as they got. Subsequent to the Anchorage disaster, John Kerry made a brief trip to the mainland as Biden’s environment envoy, out of which nothing much seems to have come.

And now Ms. Sherman’s turn.

One knew what was coming by way of the kvetching the Biden regime indulged in as the visit was planned. Sherman wanted talks with FM Wang Yi, as noted her senior in rank, while knowing full well that this kind of protocol counts greatly in matters of state. A fuss was made. No, we invite you for talks with Vice-Minister Xie, your counterpart, the Chinese replied. In the end and as if mollifying a child, the Chinese settled on talks with Xie, after which she would “meet” Wang, in all likelihood very briefly and very certainly as a courtesy.

One would have thought the Biden people could have opened up with a little more grace. But no. Let the semiology of American superiority prevail. In the event it is hard to believe what took place, by all accounts, when Sherman met Xie.

When I was a schoolboy you read the Baltimore Catechism no matter whether you lived in Tucson, Dubuque, or Bangor. So it seems at Blinken’s State Department, no matter what floor you are on. Sherman, I kid you not, read Xie the riot act on—let me consult the paragraph above—Xinjiang, Hong Kong, human rights, press freedoms, Taiwan, “the rules-based international order,” and other matters we have exaggerated, misrepresented, and weaponized. She also mentioned the South China Sea question, which is more China’s business than America’s, and the no-evidence accusation the previous week that the Bureau of State Security in Beijing recently colluded with domestic hackers to invade Microsoft-made computer systems.

What in hell are these people thinking of? Blinken brings the Chinese into an Anchorage conference room—at the Hotel Captain Cook, if you please—and tells them, Gentlemen, 4 and 3 make 7. When that fails abjectly, Sherman goes to Tianjin and tells them, Look, 5 and 2 make 7. And we expect to get somewhere with China. Jeez.

The crux of the American position is fairly upsummed this way (and the Biden regime is trying on the same with the Russian Federation): We want to knee you in the groin on questions of this that, and the other, those things that are useful for our propaganda ops as we wage a new cold war against you, but we want to cooperate on climate change and other sorts of virtue-signaling matters. Sherman put it this way after the Tianjin flop, as uncritically reproduced in The Times:

The relationship between the United States and the P.R.C. is a complex one, and our policy is very complex as a result.

What blarney. What utter, bloody blarney.

The truth is the Biden regime has no China policy—or much of a foreign policy altogether, as considered previously in these pages. Berating the Chinese as just enumerated is not a China policy: It is an admission the Biden regime cannot figure out anything that would even resemble a China policy. Security in the western Pacific, the mess the previous administration made of the trade regime, investment and financial-market protocols, a genuine sorting out of the cyber-hacking problem, cooperation toward an authentic settlement on the Korean Peninsula: Nothing and nothing and nothing and nothing and nothing from the Biden “folks.”

I have greatly liked what the Chinese have taken to saying in response to the most muddled American administration to come along since… since the Clinton, Obama, and Trump administrations. In Anchorage the Chinese side resorted to some artful immanent critique: Don’t lecture us on human rights, don’t tell us about your fraudulent “rules-based international order.” Xie and subsequently Wang went further in Tianjin and afterward.

Xie to Sherman:

The United state is the inventor and patent and intellectual property holder of coercive diplomacy….

The competitive, collaborative, and adversarial rhetoric is a thinly veiled attempt to contain and suppress China….

The U.S. side’s “rules-based international order” is designed to benefit itself at others’ expense, hold other countries back, and introduce the law of the jungle.…

The China–U.S. relationship is in a stalemate fundamentally because some Americans portray China as an imagined enemy….

Xie followed these remarks with a list of demands China deems necessary if relations are to be repaired. These include lifting the many sanctions Washington has profligately imposed on Chinese companies, executives, and officials, dropping its campaign against Huawei, the industry-leading telecommunications company, and reversing its classification of Chinese correspondents in the U.S. as foreign agents.

And Wang, two days after “meeting” Sherman:

The United States always wants to exert pressure on other countries by virtue of its own strength, thinking that it is superior to others. I would like to tell the U.S. side that there has never been a country in this world that is superior to others, nor should there be, and China will not accept any country claiming to be superior to others. If the United State has not learned to get along with other countries on an equal footing by now, then it is our responsibility, together with the international community, to give the U.S. a good tutorial in this regard….

Wow. Wow.

I have argued for many years now that parity between the West and non–West is a 21st century imperative, no matter whether any of us approves or fears this eventuality. Until Anchorage, in my read, the Chinese (and the Russians, who are watching, make no mistake) had asked in a hundred different ways for the Americans to accept this. As of Tianjin, a new reality confronts us: The non–West is no longer waiting around for the Americans to understand our new era; it now determines to define this on its own terms, Washington’s cooperation or resistance being as they will turn out to be.

Tianjin has another lesson for us that is equally not to be missed. It is now perfectly plain that the Biden regime, as all those preceding it and in all likelihood as all those to come, simply cannot accept that it is time to address other nations as equals. It steadfastly will not do so. One could see this coming from the preposterous kerfuffle Washington made over who Sherman would meet. Sheer insecurity, in my read. The something-to-prove behavior of the bully on the block who knows within that the only thing he has left to prove is his long-accumulated weakness.

Two new truths. These are big, very big, the sort of thing that qualifies as history.

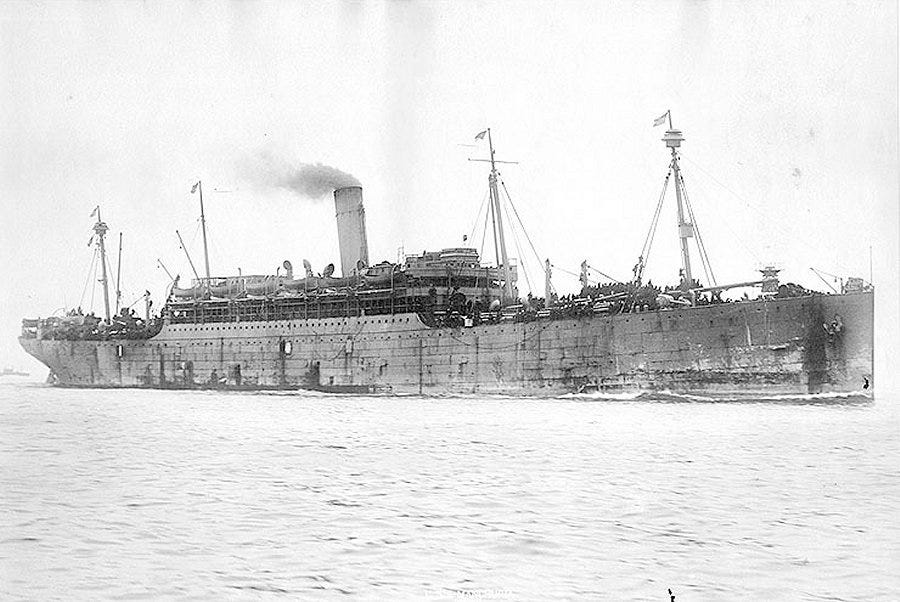

In my view, it was across the Pacific that the lapse of America’s brief imperial period was fated first to fail. Onward from TR’s 1905 “imperial cruise” aboard the SS Manchuria, the Pacific has been an American lake in our consciousness. Colonize those inferior Koreans and keep them down, Roosevelt told the Japanese: We’re fine with the plan. We shall rid the Philippines of those impudent Aguinaldistas, with their preposterous demand for self-determination, even if it means the head of every last one of them must be displayed on a pole.

The Pacific, in short, was the venue of our declaration of empire in its purest, most confident form. The Europeans, after all, and even the Russians, had civilizations one could take seriously. And they were white. Asia and Asians were a cakewalk by comparison, our superiority evident even at a glance.

I do not wish to overstate matters, but U.S. policy has ever since displayed this thread of thinking in its weave. The last time we had serious Sinologists at State was at mid-century, when Owen Lattimore, John Service, et al. consulted for or otherwise served the department. Most or all were purged, of course, during the “Who lost China?” frenzy, and they have never been replaced. They had lived in Asia and spoke its languages, knew its literature and traditions and myths—understood it, altogether, from the inside out.

This sort of understanding is long since by the boards. This is the preference of empires: They have no need or desire to see others or listen to them. It is enough to advance the mechanisms of imperial control and maintenance. There have been legions of more or less ignorant Antony Blinkens and Wendy Shermans, graduates of the School of Demotic Diplomacy, to get this done.

The imperial preference and the imperial undoing. And now ours is at last on the way to its own undoing. Let us put this on the table as the theme of our time.

Footnotes. James Bradley’s excellent The Imperial Cruise: A Secret History of Empire and War came out from Little, Brown in 2009. It is to be found here. Moon of Alabama rendered a usefully close analysis of the Sherman talks in Tianjin. It is here . The South China Morning Post also published good work on this topic, here.