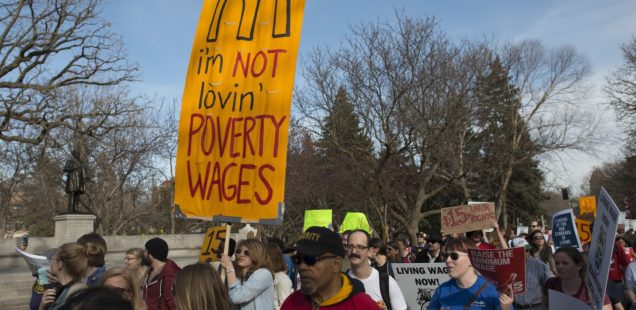

“Minimum wage mythologies.”

Fifty years of analytic scams.

The Congressional Budget Office’s latest assessment on the impacts of President Biden’s proposed increase in the minimum wage to $15/hour, issued at the beginning of February, is both predictable and disappointing. While acknowledging that 27 million people would get a raise (which would help alleviate a poverty rate that now stands at 11.8%), it also makes the questionable claim that there would be 1.4 million jobs lost over 10 years. Hence the CBO “scores” the proposal negatively, as a net cost to the government of $54 billion over 10 years.

Biden is seeking to fast-track the minimum wage proposal as part of his $1.9 trillion Covid–19 relief package via a budget reconciliation process (part of which is a congressionally mandated assessment done by the CBO). Let us watch and listen closely in coming days and weeks.

There are multiple problems in the CBO’s analysis. Read it closely and it is evident that it is politically driven in the interests of corporations, judging from the random distribution of possible changes in employment that the CBO appears to focus on, accentuating the most negative in terms of adverse budget deficit outcomes.

First, it is questionable whether any economic forecast has genuine validity over a 10–year time frame (even as it conveniently exaggerates the cost of the proposal). A more problematic aspect is that the CBO’s assessment parrots outdated analyses that have been undermined by a growing body of empirical evidence to the contrary.

As early as 2004, an OECD study suggested that “the evidence of the role played by employment protection legislation on aggregate employment and unemployment remains mixed” and that the evidence supporting the traditional view that high real wages cause unemployment “is somewhat fragile.” More recent studies have indicated that a significant rise in the minimum would result in a drop in overall poverty rates.

Bloomberg columnist Noah Smith cites “ a 2019 paper by Arindrajit Dube [that] finds that doubling the minimum wage would result in somewhere between a 2.2% and a 4.5% drop in poverty…A 2018 paper by Kevin Rinz and John Voorheis, of the Census Bureau, finds that minimum wage rises substantially increase income at the bottom of the distribution over a 5–year period.” There are other analyses in a similar vein, all of which point to the fact that President Biden’s proposed minimum wage increase to $15/hour is, in fact, a highly effective anti-poverty policy.

Second, the vitality of our economy is dependent on the spending power of the population—that is, unless we want to resemble China of the 1990s, with its export- oriented production based on cheap labor and suppressed local consumption. To get the economy back on track, spending power must be in the hands of those who actually spend in the real economy. This is a question of demand, plainly and simply, even if mainstream economists typically flinch from this reality. This is why decades of wage stagnation in behalf of corporate profits is has been shortsighted almost beyond one’s belief.

Third, the problem with our economy today is that the growing gap between the real wages and productivity violates the traditional relationship between real wages and consumption. If the productivity of each worker is rising strongly, yet that worker’s capacity to purchase (the real wage) is lagging badly behind, how does an economic recovery reliant on growth in spending sustain itself? All of this is in addition to the usual disclaimers that a purely free market does not exist for labor given the massive prevailing imbalances between workers and employers because of decades of attacks on the working class and their corresponding social welfare benefits.

Survival of the unfittest.

Fourth, arguing that low wages are a condition for high employment effectively treats employment as a substitute for the welfare state. But maintaining low wages not only generates misery for the employees; it also sustains zombie businesses that should not exist according to the most elementary laws of economics. No worker should be paid below what is considered the lowest tolerable standard of living just because a low wage-low productivity operator wants to continue to adhere to exploitive labor practices.

Such practices should not become a template for the economy as a whole. If small businesses, or any businesses for that matter, consider they do not have the “capacity to pay” that wage, then a humane society will say that these businesses are not suitable to operate in said society’s economy.

Rather than sustaining feudal labor practices, firms should have to restructure investment to raise their productivity levels sufficiently to have the capacity to pay socially consonant wages or disappear. That would give us an economy that pushes productivity growth up and increases standards of living. The few working people who cannot thrive in such an economic environment should be able to rely on robust public services and a social safety net, not on a dysfunctional “free” market, where the position of the working class has been under sustained attack for almost half a century.

In 1844, the 26-year-old Karl Marx remarked that an enforced increase of wages “would be nothing but better payment for the slave, and would not win for the workers their human status and dignity.” While we may have advanced beyond the brutally exploitative conditions observed by Marx, the truth is that the proposed minimum wage increase represents the barest minimum we can and should do to enhance the existing social contract.

No matter how much we fiddle with wages and employment, if essential needs such as housing, health care, and education are left to the mercy of a merciless market, our society will remain precarious and its members miserable and angry. Which could well mean more January 6th events in our future.

Albena Azmanova: associate professor, University of Kent; author of Capitalism on Edge: How Fighting Precarity Can Achieve Radical Change Without Crisis Or Utopia (Columbia University Press, 2020).