“Jobs and prices.”

Maybe there is a labor shortage.

In 1964, Potter Stewart, then mid-career as a Supreme Court Justice, famously described how he recognized obscenity. “I know it when I see it,” he said.

This somewhat vague, subjective, reply hits at the heart of the current economic debate in the U.S. and beyond—the inflation debate, this is to say. Everybody, economist or layman, seems to have his or her definition, and everyone thinks he, in some superior fashion, will “know it when I see it.” Alas, if only it were so easy. Policymakers, not to mention economists, have got it wrong many times before.

In general, inflation as popularly understood appears when there is chronic excess demand relative to the real capacity of the economy to produce—in familiar terms, too much money is chasing too few goods. In policy terms, it means we see a constant tension on the part of policymakers to get the balance between demand and supply correct to avoid excessive price pressures.

What’s the state of play today? In a word, alarming. Consumer prices haven’t risen this fast in years: Over the past 12 months, inflation in the U.S. has risen by 5 percent, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. This is its quickest pace since August 2008. The core consumer price index—which strips out volatile food and energy prices—is rising at its fastest annual rate since 1992.

If one is to judge from muted reaction of the bond market, these inflationary pressures are likely to prove transitory, a product of the temporary supply and demand distortions in the labor market brought about by Covid–19. Indeed, state and federal unemployment claims data—which count unemployed people who have already filed a claim and who are continuing to receive weekly benefits—appeared to confirm that we had enormous slack in the labor market.

More recently, however, other competing sources of labor data—notably, the Bureau of Labor Statistics payroll and household surveys—have indicated more and more signs of labor scarcity, which would better explain the recent sharp price increases. Far from proving transitory, these labor shortages are multiplying, and the economy is increasingly rife with stories of businesses, particularly in the leisure and service industries, that are having difficulty attracting people back to work despite offers of significantly higher wages.

The pat explanation (especially from those on the right) is that the (relatively) high social-welfare supports legislated during the Covid–19 pandemic have created disincentives: People, it is argued, see no reason to rejoin the labor force so long as they can remain on the so-called “Biden dole.”Add this to a potential labor supply shock: We have had more than 33 million reported cases of Covid–19. A significant minority of those infected have had “long haul” symptoms. In some cases, these symptoms have been highly debilitating and are therefore leading those who deferred retirement to take this moment to exit the workforce.

Hence, it might be a mistake—and a big one—to assume there is still a large potential supply of labor that will enter the job market as and when benefits run out, and who will therefore curb incipient inflationary pressures.

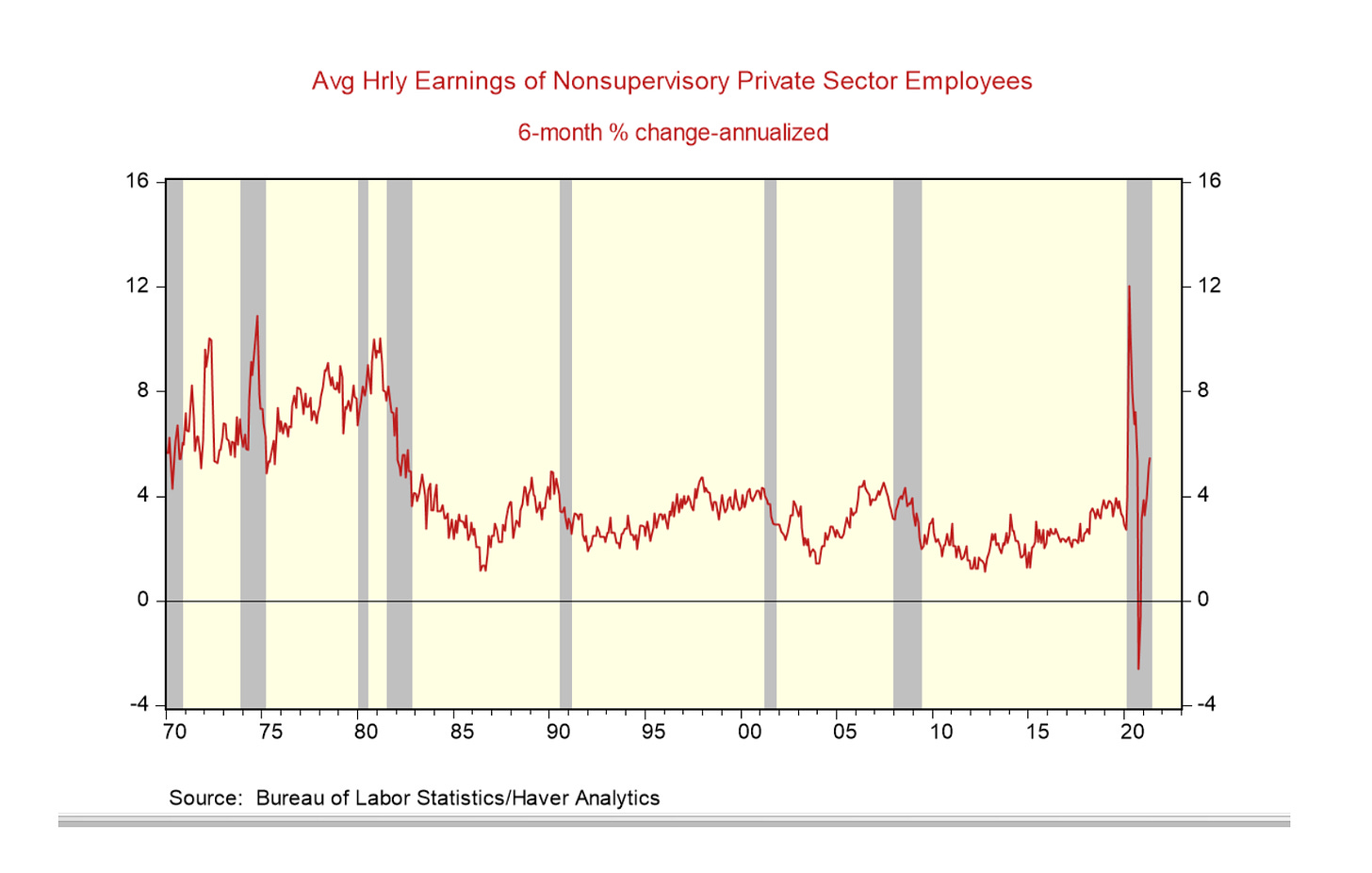

We should undoubtedly celebrate the recent gains in average hourly earnings, especially in the low-wage hospitality-and-leisure sector where, after decades characterized by paltry and stagnant wage growth, the annualized rate of wage growth over the past three months has been running at 17 percent. But if these wage gains are ultimately eroded by rising inflationary pressures à la the 1970s, that might mean more erosion of working– and middle-class living standards.

How will that play out in the 2022 elections?

The labor market appears to hold the key here, so let’s first take a broader look at its overall condition, where there is both good and bad news:

One major bit of good news is that the official unemployment rate, according to the Household survey measure, stands at 5.8 percent as of this week. Yes, there are huge statistical anomalies, but it is worth recalling that one year ago, huge swathes of the country were in shutdown mode and the unemployment rate stood at a Depression-level of 13.3 percent. Even more significantly, the previous two rounds of survival checks, which totaled $2,000 per person, “significantly improved Americans’ ability to buy food and pay household bills and reduced anxiety and depression, with the largest benefits going to the poorest households and those with children,” according to an analysis of Census Bureau data. These data serve as further evidence that direct cash payments are an effective tool in reducing poverty.

And wages are rising at a rate not seen in years, low-wage workers the chief beneficiaries. The details were spelled out by the economist Jason Furman, who headed the Council of Economic Advisers under Barack Obama. Furman pointed out last week that adjusted wages for production workers and those in non-supervisory jobs grew at an annual rate of 9.1 percent in April and May, which is “faster than in any pre-pandemic two-month period since the early 1980s.” Further, Ian Shepherdson, the chief economist at Pantheon Macroeconomics, tweeted last week that, in the low-wage hospitality-and-leisure sector, the annualized rate of wage growth over the past three months has been 17 percent.

Paradoxically, the good news on wages might have some problematic implications going forward insofar as the recovery might well be generating long-dormant inflationary pressures to a degree not seen in decades. Market analyst Frank Veneroso has long highlighted statistical anomalies in the employment numbers. Why? Per Veneroso:

The increase in continuing claims since pre–Covid–19 shows a loss of employment almost two times the payroll and household job series losses.

Although that might be appear to be a statistical quirk that matters only to academic economists, the real-world issue is that the Biden Administration has been constructing a very robust fiscal policy response on the basis of the much higher continuing claims number as a measure of the unemployed in justifying fiscal stimulus programs in the pipeline (notably the infrastructure plan and the Green New Deal).

If the continuing claims data were wrong, that should start to manifest itself in the wage data. And that appears to be happening: Overall wage growth, based on last week’s May jobs report, show average hourly earnings rising at a 6.1 percent annual rate, and in the prior month they rose at an 8.7 percent annual rate, which would suggest a rapidly tightening labor market.

And here’s where the disparities in the various measures of employment might prove very significant as regards the inflation debate and the corresponding policy response that ought to be implemented.

Veneroso has a compelling explanation for the divergence between the 5.8 percent unemployment rate and continuing claims data (which has hitherto suggested a much higher level of unemployed). He contends the odds are high that continuing claims are inflated by “double dippers” collecting but at the same time working and getting paid under the table. If this is true, the payroll and household employment series may overstate job losses and understate employment because double dippers will tell the household survey they are not employed, and firms that are employing double dippers will tell the payroll survey that those they are paying under the table are not on their payrolls.

That sounds like the sort of underground economy phenomenon that has long characterized economies such as Italy’s but has apparently been less prevalent here in the U.S. Is there any evidence for the above hypothesis?

Yes. Let’s look at this from another perspective: money.

In this pandemic, the demand and hence the supply of circulating currency should fall for two reasons. First, currency can carry germs including the Covid–19 virus (or so we were told until recently), so people use credit cards more than before because they can be sure payment involves no Covid–19 contact. Second, the share of online purchases in total goods purchases has risen. Online purchases do not involve currency.

But data from the Federal Reserve shows a steady increase of cash in circulation, despite these pandemic constraints. The discrepancy between where currency outstanding is now and where it should be given the reduction in currency use during the pandemic suggests that new demand reflects increased use of currency to pay workers who are at the same time collecting unemployment claims.

Add to this the consideration that many potential entrants in the labor market may be afflicted with long haul symptoms that preclude their re-entry into the broader labor market. This should be particularly true of older people in more physically demanding occupations. The veteran construction worker cohort would be a very likely target, which is consistent with data from the St. Louis Fed illustrating that construction employment fell by 20,000 jobs in May, compared with April, and was still 225,000 lower than in February 2020 (as cited by market analyst Wolf Richter). This might help explain today’s excruciating scarcity of experienced construction workers (which means higher wage payouts but also rising housing costs, at a time when house prices are exploding again).

All of these factors would go some ways toward explaining the alleged “labor shortage” while also being consistent with the strong gains in wages that we are seeing right now in the U.S. labor market. Yes, it is true that many of the Covid–related support measures are being scaled back and all will be ended by September. But while this may resolve the statistical divergences among the various measures of the labor market (as “underground labor” goes “above ground” again and is therefore counted in the employment data), this is unlikely to create renewed slack in the labor market, given that many of these people have already been working unofficially.

The big policy question is: How long can the administration and the Federal Reserve ignore this burgeoning evidence of growing labor scarcity? And if this inflation story turns out to be less than transitory, what kind of a political response will it engender at a time when the working class and millennials, in particular, are finally starting to recover from a multiplicity of economic calamities over the past two decades?

Recall that we still live in a profoundly unequal society, where so many the past several decades’ economic gains have been increasingly funneled to a smaller number of people at the top. Those people at the top tier aren’t the ones who will be affected by rising inflation. Instead, it will be the increasingly hollowed out middle class, along with a growing tide of serf labor, still experiencing considerable economic uncertainty.

Unfortunately, this represents a significant proportion of the population, whose only recently attained hard-earned gains could be potentially eroded by the scourge of a 1970s style inflation. What will that mean for the country’s political configuration if ongoing inflationary pressures persist into the 2022 midterm elections with a country whose democratic institutions are still in critical condition?

Perhaps eventually the variants will point to what’s logical. Exactly where Dean Baker says we should cooperate with China, healthcare and energy conversion. Our neoliberal ways don’t allow our economy to adjust to plague; but if our economy BECAME HEALTHCARE, then care of “long haul symptoms” as well as protections for those having thus far missed the thing would be built-in.

I’ve looked around for a slogan. On fb there used to be IIRC two “New New Deal” pages. Don’t see them there at all now, but New York State Assembly member Yuh-Line Niou has a 2020 share with just that title. Not a bad share either. Thought of calling a party The Great Reversal Party, but “Solidarity” might be a good name too. Lots of Cuban motifs.

“Global capitalists have turned back the clock to the early days of the Industrial Revolution. The working class is increasingly bereft of rights, blocked from forming unions, paid starvation wages, subject to wage theft, under constant surveillance, fired for minor infractions, exposed to dangerous carcinogens, forced to work overtime, given punishing quotas and abandoned when they are sick and old. Workers have become, here and abroad, disposable cogs to corporate oligarchs, who wallow in obscene personal wealth that dwarfs the worst excesses of the Robber Barons.” Chris Hedges around the end of May