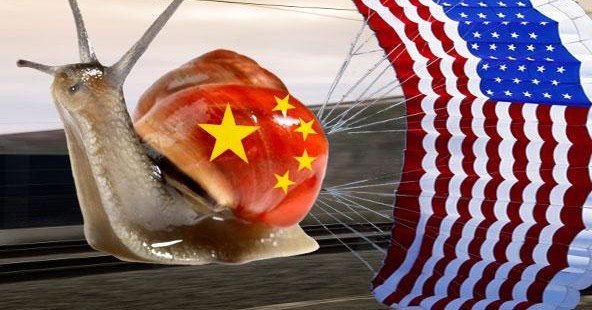

How Long Will China’s Slowdown Hurt U.S. Markets?

China’s economy, after prolonged signs of weakness, now appears to be stabilizing. Good news? That is not clear, because it is stabilizing at a lower rate of growth. The great, big boom years—14.2 percent growth at their rosiest, in 2007—may be over. This is important news for all of us and not necessarily what we want to hear.

After last week’s mauling on Wall Street, driven by the lower revenues and profits reported by a long list of market leaders, this question comes with a sharp edge.

For decades, the East Asian economies were addicted to healthy U.S. growth because they lived by an export-oriented economic strategy. There was not much of a domestic market in, say, Korea or Thailand; if America did not buy what Asians produced, nobody would—and the Asian economies would go into recession.

Now the slower growth in China this year is directly related to the performance of U.S. companies that are reporting third-quarter drops in sales and earnings. Consider the list (or part of it): Google, Apple, Microsoft, Intel, IBM, McDonald’s, Caterpillar, General Electric, Coca-Cola. They have all just reported their third-quarter results and have come in below market expectations. And they all have significant exposure in China.

For much of this year, many analysts placed high hopes on China’s ability to halt and then reverse a worrisome slowdown in its economy. That optimism was misplaced, and we need to avoid making the same mistake in reverse. China’s slowdown is not the only development weighing on U.S. corporate performances. Europe is a factor, of course; so is weak demand at home. In reporting a 22 percent drop in profit, Microsoft noted a shift among consumers away from PCs toward smartphones, computer tablets, and other mobile devices.

But the China factor must not be missed or dismissed. Gregory Hayes, chief financial officer at United Technologies, reckons that 53 percent of global economic growth will derive from China in the year to come. This is why China’s numbers now are being studied as if they were tea leaves or tortoise shells in an I Ching reading. A slower China means a slower America, just as a slower America produced a slower East Asia in decades gone by.

According to statistics released last week, China’s slowdown appears to have leveled off during the third quarter. Inflation is down and exports are up. Industrial production also turned upward, finishing the period with a growth rate of 9.2 percent. Retail sales grew 14.2 percent, a modest but welcome gain over the previous quarter’s 13.2 percent. Capital investment also bounced back. For the quarter, the economy grew at an annualized rate of 7.4 percent.

What does this raft of numbers mean? It is a little contradictory. It means that China has now finished its seventh straight quarter of slower growth. Third-quarter 2012 will go into the books as China’s weakest three months since the first quarter of 2009, when the world was absorbing the shock of the U.S. financial crisis. It means 2012 will be shown the poorest performance since 1990. Growth in 2011 came in at 9.3 percent.

But it also means that China will probably meet its official growth target this year of 7.5 percent. And it means that domestic consumption—that retail sales figure—is at last overtaking investment as an economic driver. Here is where it gets interesting. Beijing’s leaders appear to be quite happy with their 7.5 percent.

This is something new. It suggests a corner has been turned in the maturation of the Chinese economy and that its performance from here on out will drift ever so gradually toward the kind of growth expected of advanced economies. The “miracle” years ended in Southeast Asia, they ended in Japan, and they will end in China.

Some of China’s earlier spike in GDP resulted from a big push on infrastructure before the 2008 Olympics. From hotel accommodations to broadband access to international news crew needs, the country was in warp speed to complete projects that would showcase China to the world and make the event a success.

Still, until recently, the rest of the world could count on China producing a minimum growth rate of 8 percent annually. Below that level, the risk of social unrest began to appear. In this respect, we have all been invested in the interests of Communist apparatchiks in Beijing who have been eager to protect their power and position by keeping the great broad masses happy.

This has now changed. For one thing, with the economy advancing at less that 8 percent all year, there has been no social unrest—or no appreciable increase in it— because employment levels have not been significantly affected by the slowdown. For another, a lot of the high growth in previous years came from speculation in a hot-as-hell property market, and therefore did Beijing little good so far as developing the economy as it wanted and addressing the still-looming problem of income inequality.

Bottom line: China will continue to grow its GDP at a rate the rest of the world can only stand back and envy. But it is likely to settle into a more mature, more sustainable range in the 6 percent to 8 percent range. (In its World Economic Outlook, the International Monetary Fund has just forecast a growth rate of 8.2 percent for China next year.)

China’s slowdown this year has clearly clobbered dozens of U.S. corporations doing business with the mainland. They are all quite prepared to say so. But it is a waste of time assuming current conditions are temporary. Better to look across the Pacific and understand that China is turning a page.