“China manufactures things and social cohesion.”

And America manufactures financial instruments and decay.

What has been described in the American press as a Chinese crackdown on private enterprise is more in the nature of an existential choice for Beijing. The government has decided to live by producing stuff instead of by betting on financial speculation.

China wants to be a nation full of engineers, not financial engineers—of computer chips rather than chocolate chips, of innovation over financial experimentation. Additionally, Beijing wants an education system that actually educates, rather than creating a cottage industry of woke credentialism but little in the way of genuinely independent thought, or skills appropriate to prosper in the 21st century.

This is the context in which we should view Beijing’s recent crackdown on a number of prominent, publicly quoted companies on China’s stock exchange, which include some very significant global names across a broad swath of industries. Among these are some huge corporations well known to Western investors, such as Jack Ma’s Alibaba and its financial service subsidiary, Ant, e-commerce delivery companies (such as Didi, the Uber of China, or Meituan, a food-delivery service company), as well as private-education companies TAL Education Group and Gaotu Group. Beijing has come down on all of them lately.

Yes, Beijing’s actions created a predictable stock market plunge, the sort of thing that exorcises America’s policy makers, who act as if economic calamity awaits if the Fed doesn’t react to cushion a 20 percent fall in the S&P 500. The resultant rescue packages say much more about the priorities of our political class relative to those of Beijing, notably how the former reflect the exceedingly destructive financialization of the American economy. This is a pathology that describes the increase in size and power of a country’s financial sector relative to its overall economy, along with an upsurge in the economic and political power of those who derive their income from financial investments (that is, the rentier class). That’s the United States writ large today, a fate that China is seeking to avoid.

And yet, much of the Western commentary on Beijing’s actions has been unremittingly negative. Typical is Stephen Roach, former chief economist at Morgan Stanley, now a senior lecturer at the Yale School of Management. In a recent column decrying Beijing’s actions, Roach puts his argument this way: “China’s regulation of its spirited tech sector could be a tipping point for the economy.” He goes on to lament the heavy-handed use of regulation “to strangle the business models and financing capacity of the economy’s most dynamic sector”—which, Roach contends, will “weaken confidence and the entrepreneurial spirit.”

To borrow and bend the old adage, you can take the boy out of Morgan Stanley, but you can’t take Morgan Stanley out of the boy.

Roach still retains a Wall Street-centric bias in a country where the stock market remains the ultimate arbiter of the American experience. How many times do we find ourselves in an elevator, in an airport terminal, or at home looking at a screen with stock numbers whizzing by, and people yammering about how America is somewhere on the spectrum between wonderful or about to disintegrate because of a 5 percent swing in Apple’s share price? How did we get to a national economic conversation that is dominated by chatter on the stock gyrations of GameStop, when this is simply an economic irrelevance for most of the 330 million people who live in this country and are struggling to sustain a modicum of economic security?

It is true that if one were to assess America’s “entrepreneurial spirit” via stock market metrics, as Roach apparently does, it would suggest that the U.S. has been stunningly successful: As economist David Goldman has noted,

In 2010, the five biggest tech companies accounted for just 11 percent of the market capitalization of the S&P 500; by September 2020, their share of the index had doubled to 22 percent. Just ten companies in the S&P 500 hold two-fifths of all the cash balances of index members, and all but one is a tech giant…. The top three cash holders in the S&P—Microsoft, Apple, and Google—hold a fifth of all the cash held by index companies.

On the other hand, Goldman goes on to observe that these companies’ profits have increasingly been the product of oligopolistic rents, rather than product innovation:

Apple is so cash-rich that it has bought back $327 billion of its stock since 2012.That explains why its stock price has risen by 82 percent in the past six years even though its operating income has barely changed.

Far from putting cash into productive R&D investment, Apple’s increasing financialization provides a case study of precisely the kind of situation Beijing is seeking to avoid: companies deploying cash flow toward stock buybacks rather than investing in domestic manufacturing facilities to enhance America’s productive investment and employment.

We can find multiple examples of the two countries’ diverging economic and social priorities. In the U.S., we ban the use of Chinese 5G equipment in American telecom networks, but few ponder why there are no longer any U.S. telecom equipment companies, an industry that was once as American as apple pie. In the 1970s the two largest telecom equipment manufacturers were American: Western Electric and ITT. They were dominant players in this business, but their names are now historic footnotes. This trip down memory lane tells us much about the sad state of the country’s industrial decline.

Other examples abound: Consider the cases of Boeing and GE, companies that were once poster boys for the success of American capitalism. Now they are but shells of themselves during their past years of glory. With its 737 MAX 8 plane, and the 787 Dreamliner, Boeing has become synonymous with airplane crashes and shoddy engineering, whilst GE, once a byword for thriving manufacturing and innovation, suffered the indignity in 2019 of being yet another target of Harry Markopolos, the accounting expert who first raised red flags about Bernie Madoff’s Ponzi scheme. Managements at both companies now focus on financial engineering rather than manufacturing capacity, much of which has been sold off or outsourced to China. By contrast, reverse stock splits and the Double Dutch Irish tax haven scam—these are 100 percent made in America!

With this story of increasing manufacturing irrelevance as our backdrop, is it really fair to suggest that China is headed on the road to economic perdition because its government decries the “spiritual opium” of computer games? A harsh charge to be sure, especially when one considers China’s own tragic history pertaining to opium addiction. Yet it seems there is some moral force to the government’s argument, which has therefore pressured China’s largest gaming company, Tencent, to announce new restrictions to limit gaming time for children under 12 to just one hour a day and two hours a day during holidays. It also said children would no longer be allowed to make purchases “in-game.”

Here in the United States, we lost our way decades ago, when we decided that the only social responsibility of a corporation was to increase its profits, community considerations, customer care, and employees be damned. Our corporations increasingly became laboratories for economist Milton Friedman’s “stockholder theory”: The idea that shareholders, being the owners and the main risk-bearing participants, ought therefore to receive the biggest rewards deriving from a company’s value-creating activities.

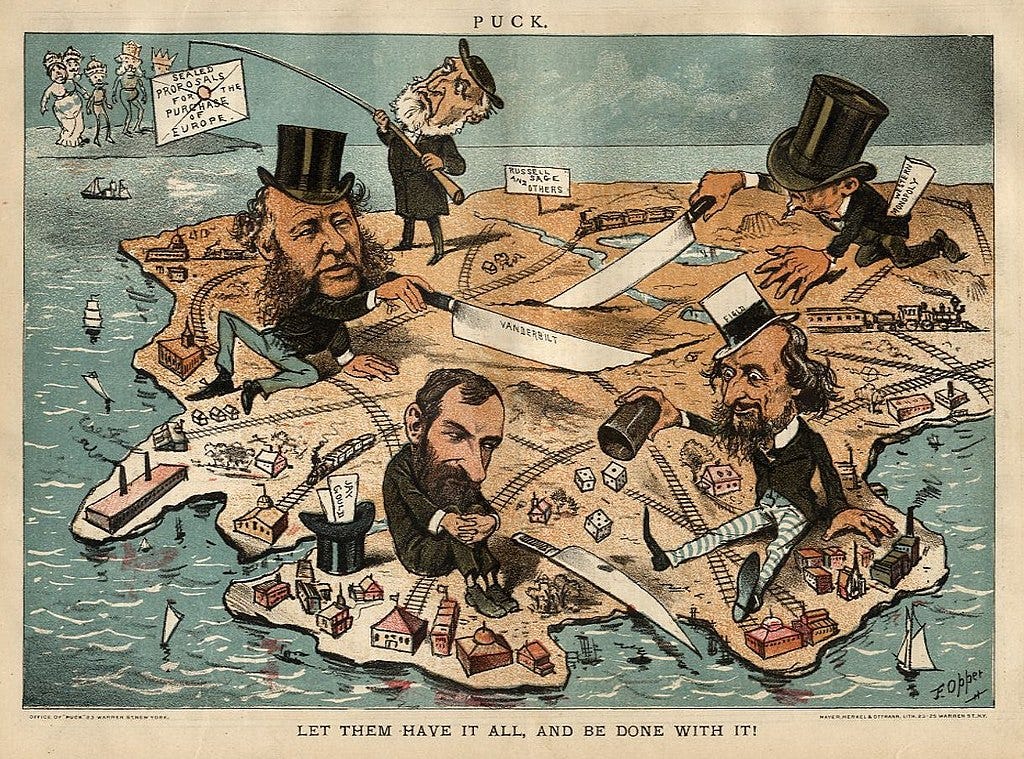

Wall Street investment banks have actively promoted and promulgated Friedman’s ideas for over half a century. Business schools provided further intellectual justification for this philosophy of shareholder capitalism in their MBA curricula. Activist shareholders, such as Carl Icahn, or private-equity buyout specialists such as Blackstone founder Steve Schwarzman (who once likened Barack Obama’s modest proposals to tax his activities to Hitler’s invasion of Poland), have targeted numerous companies in which they have performed asset-stripping exercises and drained cash flow, all in the supposed name of ensuring the primacy of enhancing stock value (as opposed to investing and improving underlying operations of the corporation itself).

Their actions often occurred via hostile takeovers, the increasing outsourcing of manufacturing activities, the promotion of massive stock buybacks or repurchases, correspondingly higher dividend payouts and, most important, the introduction of stock-based pay for top executives to align their interests to those of shareholders such as Blackstone. They were further legitimized by successive political administrations that increasingly embraced a market fundamentalist ethos whereby corporate efficiency and profitability were said to be unjustly and unwisely impinged by archaic regulation and unionization—handicaps that supposedly precluded American companies’ ability to compete globally. Try to explain that to German or Japanese manufacturers (most of whom have largely resisted this Friedmanesque siren song).

Tying corporate decision-making and its performance to stock prices to incentivize efficient resource allocation and productive transformations may have sounded superficially attractive. But the champions of this theory, including Friedman himself, never bothered to show how these outcomes could be achieved in the real world. In fact, as the examples above have illustrated, the actual historical experience has been abysmal.

American financialization represents a classic case of the tail wagging the dog. It reflects an ethos that prioritizes finance above all else in an economy increasingly characterized by leverage and the layering of debt on top of debt. It means a greater share of GDP going to the financial system, going to interest rather than profit, and largely diverting resources from a goods-producing economy to one that generates persistent asset bubbles and growing financial instability. And this has been a trend for decades.

In the 1990s, Wall Street began to repackage complex financing mechanisms into opaque, hard-to-understand instruments that were exported across the globe and culminated in the emerging-markets crisis in 1997–98. Not content with that warning shot, during the 2000s Wall Street sold derivatives based on low-quality home mortgages as well as corporate debt, and the collapse of this market brought on the Global Financial Crisis of 2008.

Beijing has been paying attention as it increasingly bets on real innovation, and targets various companies as strategic parts of a broader industrial ecosystem to promote national development. True, the government has fought to protect and promote its own companies within this sector. But what many in the West have decried as protectionist governments incompetently picking winners and losers is in fact the kind of national development policy that we used to embrace for much of our own history.

And in fact, it is possible to create world-class winners using this strategy. The Koreans have done it with companies such as Samsung, much as China has done the same with conglomerates such as Huawei—which we compulsively demonize because we can no longer compete with it. Sure, we can blame Beijing for not playing by our rules or engaging in IP theft (although we’ve certainly done the same thing historically). But we basically handed over the blueprints when we decided to move our factories from, say Cupertino, California to Shenzhen. The result? American “free market” solutions have resulted in a hollowing out of companies that were once world-class innovators, and a corresponding degradation of economic knowhow and social capital as highly skilled jobs have been outsourced.

This is the context in which we should understand Beijing’s recent crackdowns. What Stephen Roach and others characterize as Beijing’s politically motivated attacks on big-tech behemoths such as Jack Ma’s Alibaba could more accurately been seen as reining in Ma’s attempt to convert his company into a bank, all the while seeking to circumvent increased banking regulation. The action was hardly capricious. Ma was specifically warned by Chinese authorities not to do this.

Jack Ma would make a fine banker here in the U.S. He accused China’s banks of behaving like “pawnshops” by lending only to those who could put up collateral, the sort of old-fashioned banking that we used to do in America before we learned how to slice and dice credit instruments and turn them into toxic derivatives that Warren Buffett rightly called “financial weapons of mass destruction.” Imagine if we had exercised similar foresight and regulatory backbone, before our craven surrender to market deregulation enabled Wall Street titans to blow up the global economy in 2008.

Likewise, China’s State Administration for Market Regulation has been criticized for its fines on Alibaba Group, Tencent, and SF Holdings. But a closer look at these situations shows that these firms were singled out for what China’s chief regulator called “monopolistic corporate behavior,” and the fines were levied “to protect consumer interests.” That sounds like the sort of thing that we used to do in the U.S., before our tech behemoths —Apple, Google, Facebook, Microsoft— gobbled up smaller competitors and began stifling competition and actively suppressing competitive innovation. Ironically, concerns about market competition and innovation appear to be a new focus for the Biden administration, reflected in the appointment of figures such as Lina Khan, long known for her work in antitrust and competition law in the United States, as chairperson of the Federal Trade Commission. Why is China getting blasted for essentially doing the same thing?

Similarly, the crackdown on private-education companies—cram schools—should be seen as an attempt to curb the kind of credentials arms race we have in the U.S., a process that has exacerbated prevailing inequality and social alienation, even as our universities continue to furnish students with worthless diplomas (at great cost) while businesses lament our skills deficit. (As usual, our now-departed carnival- barker president was early to capitalize on this trend.) It’s also worth noting that private education costs in China are skyrocketing, and exacerbating rising inequality as well as the prevailing urban/rural divide (these companies generally operate in urban areas).

Attacks on private cramming factories such as TAL Education Group and Gaotu Group should be seen as a deterrent to unnecessary credentialism, not an attack on necessary education per se. It’s not as if Beijing authorities are saying math is Western and needs to be replaced with Han math or Confucian physics—which would be the real equivalent of what we are currently doing in many of our universities, where the extremes of woke ideology leave us with the sight of medical school professors apologizing for referring to a patient’s biological sex on the grounds that “acknowledging biological sex can be considered transphobic.”

We have a multitude of crises that we are seeking to address in the U.S. But there is a growing skepticism in the ability of American capitalism to deliver on its economic promise of prosperity. And there is increasing evidence that our elite educational institutions are doing nothing more than creating a self-perpetuating upper-class rich in terms of capital and diplomas, but providing little in the way of genuine scholarship or broadly-based social economic welfare.

That is precisely the kind of thing China is seeking to avoid. Unlike the Fed, they are not content to fan speculative excess. Stock market investors may be unhappy, but far from destroying consumer confidence, the measures Beijing now undertakes might have precisely the opposite effect. As fund manager Yuan Yuwei argued (cited in the blog Moon of Alabama), “Housing, medical, and education costs were the ‘three big mountains’ suffocating Chinese families and crowding out their consumption.” Yuan went on to describe these measures as “the most forceful reform I’ve seen over many years, and the most populist one. It benefits the masses at the cost of the richest and the elite groups.”

Beijing is prioritizing social cohesion above the narrow interests of financial rentiers. Today’s tech rout signals a profound assertion of national strategic interests in China, not a crushing of the nation’s growth model. Would that American policymakers had demonstrated similar backbone in decades past.

Thanks for a lucid explanation of how a more people-orientated country reigns in corporate hubris for the longer-term better good of all.