How China Is Building the Post-Western World

Beijing’s Belt and Road project may be the largest single infrastructure program in human history.

ot infrequently, I bang on in this space and elsewhere about “parity between West and non-West.” I consider achieving this the single most pressing necessity of our century if we are to make an orderly world out of the deranged, dysfunctional botch those responsible for it still get away with calling “the postwar order,” “the liberal order,” “the global order”—all of which are polite ways of saying “the Western-designed, Western-imposed order.”

Parity: What does this mean? It sounds like a flaky abstraction worth years of paychecks for the think-tank set. Why should one want to see it realized, given that so much of the non-West is ungiven to our “free-market democracy” after all we have taught them of its virtues and all we show them by example of its rewards? What would the world come to were it somehow to do without the “order,” “stability,” and “market-based” everything the West is here to protect and extend across the planet?

These are among the best questions one can ask now. And, kindness of Xi Jinping, it is a good week to consider them. On Monday China’s president concluded a two-day summit in Beijing, the first of this kind, dedicated to constructing—on the ground as well as in the history books—something like a new world order. The Chinese are not talking in such grand terms. They prefer the modest “Globalization 2.0,” or—this from China Daily a few days ago—“a new trajectory for mankind.” Ni Lexiong, an emeritus professor at Shanghai University of Political Science and Law, put it this way in an interview with The Los Angeles Times: “The West and East are switching their roles.”

I do not buy into “the Asian century,” “the Pacific century,” “the Chinese century,” or zero-sum notions such as the honorable professor’s. There is always a pride factor in the consciousness of the Chinese, for whom the Opium Wars were yesterday. These expressions suggest the magnitude of events, but mislead as to the nature of the ambition. Before you know it you are trading in a civilized variant of the “yellow peril” Hearst conjured at the turn of the last century—and, to be honest, a lot of our hacks are already at it. “A post-Western world” I can live with. I subtitled a book thus a decade ago; China figured prominently in the argument, and I wrote it on a famed island that had earlier passed back from Britain’s hands into China’s.

It is a world one could sense back then but not quite see. Now it is hard upon us. It is what Vladimir Putin, who seems to have an excellent grasp of history, is talking about—the first, second, and third reasons we are supposed to detest and fear him. It is what formations such as the BRICs—Brazil, Russia, India, and China—are all about. It is what Hassan Rouhani, Iran’s reformist president, is trying to get across (as was Mohammad Khatami, the admirable reformist before him). Xi’s banner is as large as Tiananmen Square.

The West’s policy cliques, Washington’s in the lead, have four responses to this unfolding world-historical phenomenon. They ignore it, dismiss it as unlikely to work, or mark it down to cynical self-interest or a plot to accumulate power. Barack Obama and Jack Lew, his treasury secretary, gave a perfect example of the first tactic when, in 2015, they refused to join the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, Beijing’s alternative to the World Bank and its Asian affiliate in Manila. A more stupidly arrogant call one cannot imagine. Now our ever-obedient press serves us the impracticality argument and the Trojan horse argument—double scoops this week, with sprinkles on top.

When opportunities arise, there is the fourth response: Subvert any effort to supersede the liberal Western disorder by all available means, as if by taking hold of the clock’s hands one can stop time. Gandhi said it best (although the attribution is in dispute): First they ignore you, then they laugh at you, then they attack you, and then you win.

We are now in the third stage of the progression. There is no more ridicule, but the Chinese project as now fully unveiled is fundamentally wrong. It must be: It is not how we would do it. As the fourth and final stage lies in the middle distance, let us consider it in the context of this week’s confab in Beijing.

Beijing has been into big-think for a long time. In the late 1990s, when there was talk of an Asian Monetary Fund and “regional financial architecture,” China took considerable measures to stabilize other Asian currencies devastated by speculative onslaughts. It simultaneously developed formal relations with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, at bottom a creature of the Cold War. In 2001, a big step: It founded the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, bringing together the four Central Asian republics plus Russia to develop mutual interests across the board—political, economic, diplomatic, strategic, and so on. India and Pakistan—sign of the times—joined as full members two years ago.

Look at a map and forget about the South China Sea for a moment: China has been pushing westward and southwestward in pursuit of ports and land routes, stable economies, and global markets. And by “westward,” it soon became clear, Beijing meant “Westward.”

Xi became general secretary of the Communist Party in 2012 and president of the People’s Republic a year later. Since then, it has been one big move after another: He announced the AIIB, the World Bank’s aforementioned alternative, as soon as he became president. As Obama and Jack Lew folded their arms, the world piled in. The bank is now capitalized at $250 billion, can lend two and a half times that, and has 77 members—seven inducted the day before this week’s big-tent forum. (I would have loved to be in the room when Lew got word that even the British joined, which was quickly after the bank was launched.)

This week’s summit was called the Belt and Road Forum. This initiative sits atop all just outlined. When Xi announced it—again, as soon as he assumed the presidency—it was called the Silk Road Project. It is almost certainly the largest single infrastructure program in human history, intended to build linkages connecting China and the Middle East, Europe, and Africa. Side streets, let’s call them, lead into Southeast Asia and elsewhere. It is about highways, rails, power plants, bridges and tunnels, communications grids. The projects now number nearly 1,700, and the money is breathtaking: Financing—public and private investments, joint ventures, loans, development aid—will come to trillions of dollars.

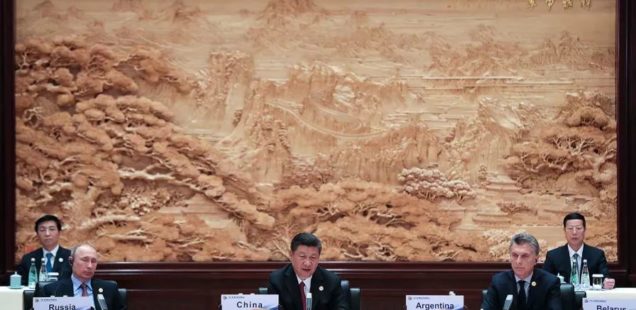

The world is listening: By rough counts nearly 30 heads of state attended. António Guterres, the UN’s secretary general, was there; so were the heads of the World Bank and the IMF. Trump nearly made Obama’s mistake: Until last week he planned to send Eric Branstad, a political hack who ran Trump’s campaign in Iowa and now has a desk at Commerce. In the end he switched to Matthew Pottinger, a former news correspondent (sometimes we make good) and now Trump’s resident Asia hand on the National Security Council.

A modest improvement, but hardly an indication that the Trump administration has any idea what time it is. Just before the forum began, Washington announced a trade deal with Beijing, but it is symbolic in the way of the Carrier jobs in Indiana. My sources in financial circles tell me Team Trump is now negotiating membership in the AIIB—the sticking point being how much the United States will contribute to the bank’s capital. Memo to President Xi: Charge Treasury a late fee.

You do not have to tell me what you have read about Belt and Road the past few days: I am reading the same stuff. The Financial Times is the only Western newspaper I know of that had the honesty to say of the initiative, “There is the potential for it to do some real good.” For the rest, it can be reduced to one or another kind of selfish skullduggery or recklessness or both.

On the ideological side: Belt and Road “is a smokescreen for the expansion of China’s power.” Beijing is “exporting its model of state-led development.” It is “dispensing with the rules of Western institutions.” The initiative is “influence via infrastructure.” On the self-serving side: “Belt and Road is inherently in China’s economic interests.” China is “developing markets for its exports.” It is “building business for its construction sector because the economy at home is slowing.” On the impractical side: “A lot of these projects don’t make good business sense.” China is saddling poorer nations with burdensome debt. Some loans will fail. There is corruption in the markets into which China is sending its funds. China’s building a railway in Kenya “that will make it easier to get Chinese goods into the country.” (There’s half a thought for you.) Another railway, in Laos, is going to lose money for more than a decade.

On and on. There are a few things going on here.

One, with exceptions, those managing American institutions—the policy people, the clerks in the press—either have no clue as to the larger import of what we now witness or simply cannot face it. Power is shifting, inexorably. This is so not merely as a natural function of the longue durée of development. It is because the West, still stuck in what amounts to a colonial consciousness, has no comeback. Anyone who has lived in a developing country that is also a former colony understands this. When was the last time the United States built Laotians a railway on any terms, never mind China’s (low-interest loans, extended terms)? Think about what a century of fraternal ties to the United States has given the Philippines: You have to start with poverty, prostitution, dope, crime, desperation—all rampant. Don’t wonder why President Duterte now likes to spend his time in Beijing (as do the Malaysians, the Thais, the Vietnamese). We—I use the term strictly as shorthand—cannot figure a nation that thinks a world with less want is a surer route to order than dominance with no serious regard for want.

Two, so long as we lose ourselves in the problems China’s initiative may develop, there is no need to acknowledge its core motivations. Is there self-interest in Beijing’s grand plans? Are there risks? Might some projects falter? Will Chinese companies make money? Yes to all. So? China also sees advantage in the prosperity of others, and this thought overarches the others by many magnitudes. This has to be squared with all the reductionist accounts of the Chinese as merely selfish.

Three, all the criticism of Xi’s Belt and Road plans now emanating from the West is best understood as a mirror. The imposition of an ideology, “the Chinese model,” a be-like-us imperative? The projection of power upon other peoples? Loans and development projects structured to the dominant nation’s advantage? “Conditionality” in the manner of the Western multilaterals? The cultivation of corruption to gain influence? The threat of intervention? Turn it all around and you have a picture of Western policy, America the most accomplished practitioner, since 1945. While the Cold War brought complications for the Chinese (as for everyone else), there is simply no comparing its record in these matters with America’s or America’s core Atlantic allies. Recall the Five Principles Zhou Enlai advanced (along with Nehru) at the Bandung Conference back in 1955, noninterference the animating thought in four of them. Xi practically recited them this week in Beijing.

“China has seized the strategic advantage,” a good source in Beijing (a plugged-in Westerner) wrote as I was drawing my conclusions. This is a very pointed reality. Emphatically, the Chinese understand themselves as a non-Western people. Depending on whom one is talking to, they are perfectly clear that their intent is to claim, for themselves and others, the fullness of human existence heretofore available only to the Westerner. This is a thumbnail definition of “parity,” maybe.

A lot of people, too far inside Western ideology and its attendant assumptions, may be uncomfortable with the thought that nations such as China are bringing centuries of Atlantic hegemony to a close. The task is to grasp that there are alternative perspectives, appealing to one’s sensibilities or otherwise—other ideas of democracy, other ideas of the place of the state, the place of the individual, the worth of public goods, the limits of the market, and so on. “Development as freedom,” Amartya Sen argued in a book of that title at the turn of this century. Westerners are unaccustomed to thinking in such terms. Most of the world still must.

Why are you so clearly in favor of a country whose government doesn’t allow printed expressions of disagreement with public policy being in charge of world policy?

This is a country that will openly arrest people for wearing t-shirts which express support for opposition to the government. You prefer that?

I agree that there is a strangle hold of corporate interests over politics in the US right now. We are no angels here, but to naively believe that Jinping’s primary goal is helping make all people more economically secure is laughably naive. He didn’t get to the top of the China power structure through sainthood…even native Chinese admit this. Why do you have a higher opinion of the man than his own people?