“And now?”

Post–Afghanistan truths and lies.

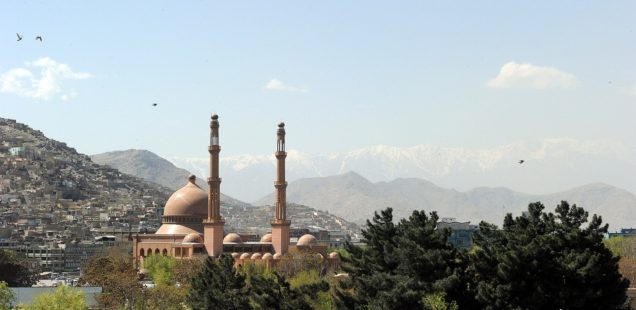

Americans are alive with questions now that Kabul has fallen, though “fallen” does not seem quite our word any more than it was in late April 46 years ago: Saigon did not fall; it rose. Vietnam became Vietnamese. Now Afghanistan will become Afghan. Whether we American like the look of an Afghan Afghanistan is of absolutely no pertinence whatsoever, though we will pretend endlessly otherwise.

Is this a debacle, a failure, or another “mission accomplished”? Should we have hung in and hung on longer? Or was the Afghan campaign a bust nine or 10 years into its 20–year duration? Were the generals lying all along, all the generals? Who’ll take the fall now, if anyone? Is this President Biden’s fault, or were four presidents, Bush II through Biden, complicit? Did President Trump, in finally drawing a line under this multi-trillion dollar disaster, box Biden in, as the latter claimed the other day? What will Afghanistan under Taliban rule be like?

Some of these are good questions. It takes a lot of nerve to pose others. We will nonetheless live with a lot of hand-wringing of this sort for a short while. Then the silence that pervades our imperial adventures will settle once again, and the most monstrous escapade in modern history will resume—unremarked upon, invisible despite its immensity to most people other than its victims.

Could America have ended its two-decade occupation of another nation differently? This is a good question in the facing-backward category. Will it do anything differently now? Will our policy cliques draw any lessons from the extraordinarily swift collapse of the Afghan campaign? These are the questions, the facing-forward questions, most worth asking now.

Secretary of State Blinken on This Week, ABC’s Sunday morning news review:

Remember, this is manifestly not Saigon. We went to Afghanistan 20 years ago with one mission and that mission was to deal with the folks who attacked us on 9/11. And we have succeeded in that mission.

Blinken is manifestly among the least intelligent occupants of the seventh floor at State in our lifetimes, a hotly contested distinction. But this remark is nonetheless pregnant with significance, a portent much worth reading into.

Here is Greg Jaffe, who had a somewhat thoughtful piece in The Washington Post (and The Seattle Times) Saturday, as the Taliban breached the gates of Kabul:

The near-collapse of the Afghan army in the space of just a few stunning weeks is prompting the military and Washington’s policymakers to reflect on their failures over the course of nearly two decades.

Jaffe managed to get the term “imperial hubris” on to The Wash Post’s opinion page, a modest feat in itself. But we say “somewhat thoughtful” advisedly. One, anyone who thinks America’s failures overseas extend back but two decades is lacking in historical perspective. They go back to the Spanish–American War or the Wilson presidency, depending on how you count.

Two, and this is the important point here, Washington’s policymakers are not reflecting on their failures as Jaffe implies. They have no intention of doing so. Blinken’s remark is the telling one: Washington will be all about denial as the Afghanistan postmortems proceed. President Biden indicated the same in his out-the-side-door remarks from the White House on Monday:

We went to Afghanistan almost 20 years ago with clear goals: Get those who attacked us on Sept. 11, 2001, and make sure al–Qaeda could not use Afghanistan as a base from which to attack us again. We did that. We severely degraded al–Qaeda in Afghanistan. We never gave up the hunt for Osama bin Laden and we got him.

That was a decade ago. Our mission in Afghanistan was never supposed to have been nation-building. It was never supposed to be creating a unified, centralized democracy. Our only vital national interest in Afghanistan remains today what it has always been: preventing a terrorist attack on American homeland.

Our policy, Blinken and Nod have just told us, is to deny wholesale our previous, often articulated policy now that it has failed. Where was the aircraft carrier Bush II used as his backdrop when he declared victory in Iraq just as the American calamity there was getting under way?

Listen carefully to all the gnashing of teeth to come: It will be all about the “how” of the Afghan adventure, not the “why” of it. Method will be the sole preoccupation. The purpose of our foreign policies, as we doggedly cling to a hegemonic period now passing, will never come in for questioning. Method, not intent, in other words.

Even in the matter of method, however, the U.S. comes up so woefully short as hardly to be believed. Afghanistan’s Potemkin president, Ashraf Ghani, was among the more preposterous creations of the Obama administration, a man who personified our American presumption that we can go around the world making all others in our image without reference to histories, cultures, or political traditions. When he fled Kabul on Sunday afternoon it was without telling his cabinet and reportedly with four cars and a helicopter full of cash—which he was not, in the end, allowed to take with him.

Per usual, our Monday morning quarterbacks in the press now focus on “Biden’s stain.” Rather than considering the broader fiasco of America’s foreign policy failures over many decades, it is the optics of the defeat that concern our Very Serious People. But none offer a constructive alternative to the fruitless 20–year status quo that got us into this quagmire, nor do most consider the broader dishonor that this turn brings on “the Blob,” the foreign policy establishment that never considers genuine alternatives to America’s perpetual wars of choice.

Was there one in this case? Of course. Trump proposed an agreement with the Taliban as a preface to the American withdrawal, but Trump and his crew were nowhere near capable of negotiating a comprehensive accord. Even now there must be finesseful, skilled diplomats on Foggy Bottom’s lower floors—surely there must be, somewhere—but we run up against the true problem here. Americans cannot negotiate diplomatic agreements with others because we have it in our heads that we are a superior power, and superiors do not talk to inferiors as if they are equals. The impediment, in other words, is imperial presumption.

There is the Vietnam analogy to consider. The mainstream press has downplayed as best it can the ignominy of America’s final withdrawal from Vietnam, notably the famous image of Americans and their Vietnamese allies climbing onto helicopters from the roof of the embassy in Saigon as the country rose. The historical reference is perfectly apt, in our view. We see similarities but also differences between these two events.

Vietnam is a nation-state with an exceedingly strong identity running back millennia. There was no chance the American military could break the Vietnamese with this history in view. Afghanistan is a multi-ethnic society—42 percent Pashtun, 27 percent Tajik, and 10 percent each Hazara, Uzbek, Alamo, Turkmen, and Baluch—atop which the U.S. purported to place a democratic apparatus in its image. Same conclusion from a different perspective: The Vietnamese identified resolutely with their nationality and fought for it—and against the puppet regime in Saigon; the Afghans appear similarly to have identified little with the Kabul government and seen no point in fighting for successive American-anointed regimes that, like their equivalents in South Vietnam, were mired in corruption to which we turned a blind eye.

The Taliban, in this connection, are Pashtun but at bottom nationalists motivated, just as the Vietnamese were, by a desire to rid the nation of a foreign intruder. Another good question: What is the relationship between the Taliban and the Afghan population? We have read little to nothing of this. What we have read reflects the view of elites in Kabul, just as American coverage of the 1979 revolution in Iran reflected the view of the educated elites in North Tehran. In neither case did our newspapers, wires, and broadcasters consider that the mosque in such societies as these is the center of life in villages and towns, the institution through which communities have historically organized themselves.

We would do well now to turn our attention to ourselves with our past in our minds. The record is poor in this regard. The mendacity of the generals as to the progress of the war in Afghanistan is a straight readout of how the Pentagon and the policy cliques portrayed the Vietnam war. Much like Daniel Ellsberg’s Pentagon Papers, two years ago we were confronted with the Afghanistan Papers, again published by The Washington Post. In them we read in painful detail of the same pervasive and perpetual lying behind our optimistic assessments (and rationales for bogus “surge” strategies).

Those too young to recall the Vietnam war era may find such comparisons a touch abstract. But for those who lived through those years they are almost ineffably poignant. What happened to our engagement in the intervening decades, our giving-more-than-a-damn, our voices? There are a variety of answers worth considering at this moment.

One, President Nixon’s decision to abolish the draft was much applauded as a victory at the time. The senior of us by age did: His lottery number was 329, relieving him of the burden of planning expatriation in France, where he was then studying. In hindsight, dropping the draft in favor of a voluntary army inevitably comprised of the poor and working poor was a disaster—the beginning of a pattern of apathy toward our wars, interventions, coups and altogether our foreign policies that, at the other end of the line, was too painfully evident in the indifference abroad among Americans during the Afghanistan campaign.

Two, the policy cliques did learn one lesson from Vietnam: Imperial policies require either domestic consensus or domestic acquiescence, and Washington’s elites, with a crucial assist from the media clerks, proceed relentlessly to cultivate the latter after 1975. “Embedded journalism” was required in Afghanistan and Iraq, implying a Faustian bargain whereby the press exchanged access for controlled information flow. Gone were the displays of journalistic independence that helped could have helped rouse the public against these wars, as the best coverage of Vietnam did. It is something close to awful to imagine a Vietnam-era American standing in a supermarket line next to your average American today. They would speak different languages, mutually uncomprehending. From informed engagement to ignorant indifference is the line to be drawn between the two.

What has become of us? This is among the very best questions worth posing this week.

We have little to say about the policies of our government and by and large want little. In consequence, the cliques making and executing policy operate in a condition of ever-greater sequestration, indifferent to public opinion, quite beyond what remains of our democratic process. This is why Washington can speak to us without facts, without logic, with little regard for the Constitution or law (domestic or international). There are too few in the public sphere listening.

If we have been so sadly numbed since 1975, it is equally to be said we have allowed ourselves to be numbed, or numbed ourselves. The village green is littered and unkempt, but we vacated it of our own volition, did we not?

As already suggested, there is little to no chance the U.S. will change course in consequence of the Afghanistan failure. They cannot, because without admissions of failure it is impossible to learn from it. And one can hardly be bothered to listen as debates over how to win the next wars proceed. That will amount to change amid no change, a common enough phenomenon in American history.

But never mind the policy cliques for a moment. Will we change—we Americans, we whose silence made the Afghanistan campaign possible two decades ago and had everything to do with prolonging it? It is the best question of all, the one we most owe it to ourselves to ask and answer.

Patrick Lawrence adds: What is the relationship between the Taliban and the Afghan population? What will the Taliban do as it forms a government? We do not yet have answers to these questions. But we should take care to note that our press is in the habit of reporting other nations from the perspectives of their elites. Iran, as just noted, is one example of this. In our time and close by, there are Nicaragua and Venezuela.

Will the Taliban, once in power, turn out to be butchers, abusers of women, and all else we read of them in the press? The record on these points is poor, and it is early days. But it is more likely, in my view, they will form a government not so unlike Iran’s after the shah was exiled to Cuernavaca: Sharia law will prevail in matters such as the hejab, but those wishing to be educated will be educated, those wishing to work will work. There will be no beheadings (as are accepted practice in Saudi Arabia). Taliban leaders have gone on the record to this effect in recent days. They have just stated that they, Sunnis, will wage no sectarian persecution of Shi’ites. It is to their advantage in the international context to proceed thus, let us not forget, and hardly is this imperative lost on the Taliban’s leaders.