“This will stop only when the American people get fed up”: American exceptionalism, the New York Times, and our foreign policy after Barack Obama

Our smartest modern military historian explains to Salon what’s wrong about our adventures in the Middle East

Part one of my interview with Andrew Bacevich, the soldier-turned-scholar who has just published “America’s War for the Greater Middle East: A Military History,” was posted last week. It focused on aspects of what Bacevich, originally, considers one long war now in its 37th year. We looked at the chronology since Jimmy Carter fatefully set the adventure in motion in his 1980 “doctrine” speech, at the American strategy and how it has developed—and at all that is wrong with it.

Somewhere around the halfway mark in our lengthy exchange, which Salon is publishing with only the very lightest edit, the conversation turned. We dilated the lens, let’s say, and found our way into all manner of subjects. He was interesting in his take on the Cold War 1950s as a prelude to the war that is the topic of his book, and on his pilgrim’s progress from West Point cadet to commissioned officer to his retirement and his scholarly work since. He collects old editions of Life Magazine, it turns out. His capacity for critical thought, the honed tool with which he earns his crust, did not develop until after he retired as a colonel, it also turns out. No need to ask about causality on this point: Bacevich is clear as to the dearth of thought in this man’s army.

Bacevich ends his book on a pessimistic note, and our conversation seemed headed in the same direction. But as he finished explaining his perspective and we prepared to part, he forced me back on a point occasionally made in this space: Find the optimism buried within the pessimism. It is usually in there somewhere. The sourest critic is an optimist, otherwise he or she would not bother. In his way Bacevich seemed to agree: The future seems fixed and grim, but it is up to us in the end.

Part 2 of this exchange, like the first half, was scrupulously transcribed by Salon’s Michael Conway Garofalo, to whom I again offer thanks.

Early in the book you cite Hermann Eilts, a former U.S. ambassador in Cairo and Riyadh. He asserted that rather than gearing up for war, the U.S. would be better served if it sought “an equitable solution to the Palestinian problem.” I thought this very interesting, given how assiduously American officials insist that Palestine has nothing whatever to do with the crisis that envelops the entire region all the way to Afghanistan. Do you agree with him?

I do. I knew him slightly. He was one of the founders of the international relations program at Boston University.

Eilts’s implication is that Palestine lies at the very core of the Middle East crisis. As long as it festers, there will be no peace.

I don’t know that. What I do believe is that Eilts is not the only person who has said that. Indeed, this is an argument that is made frequently by Arab leaders and other leaders in the Islamic world. What I believe is that we have an interest in testing that proposition. The counterargument is, “Oh, when the Arab leaders are talking about how much they care about the Palestinians that is simply posturing on their part. They find it politically useful because it plays well with their domestic constituents as a way of distracting attention from the fact that Egypt is a poorly governed, miserable place.” And so on.

I don’t know where the truth lies. I do believe we have an interest in testing the proposition. In other words, yes, let’s respond to the grievances of the Palestinians—they are real grievances—and then let’s see how that affects the attitude of other countries in the reason toward the United States. If there is no real response, then I’ll concede the argument and I’d guess that the Palestinian issue was simply contrived. But it could be that the argument is sincere and genuine, and it could be that the creation of a Palestinian state actually would provide a real breakthrough in terms of trying to bring about an end to the conflict.

Further, I also recognize that from the point of view of the Israeli government, there is not that profound an interest. From the point of the Israeli government, the status quo is not that bad. I think it’s very short-sighted, but democratically elected governments tend to be short-sighted. The way you get reelected is by responding to the needs, the complaints, the concerns of the people here today, not what their concerns might be 10 years from now. It makes democratic political sense for the Netanyahu government to sustain the status quo. They sustain themselves in power. But frankly, just because it’s in the interests of the Netanyahu government doesn’t mean that it should be in the interest of the United States to play along with him—which is, in effect, what we do: minor complaints when they expand settlements, but basically the relationship is unaffected. The military support continues to flow. The diplomatic protection in the United Nations continues.

If we were to test the thesis, I bet we’d find it absolutely transformative.

I don’t know. But I think it is imperative to examine the outcome.

How do you interpret our Syria policy? I’ve reluctantly come to the conclusion that we have been behaving with a fair amount of cynicism. While pretending to hold the humanitarian crisis as our first concern, we tacitly tolerated ISIS until recently. Even now, we continue to view Syria through a Cold War template.

The Russians called our bluff. If you recall, the American bombing campaign started [in 2014] as front-page news and then virtually disappeared. I think the Russians called our bluff last September 30 [when Russian planes began bombing runs]. In my view, the object all along has been to eliminate a Russian ally, the last in the Middle East. Only since Moscow moved last September have we become serious about countering the Islamic State.

I hadn’t thought about it in those terms. You may attributing clearer calculation on the part of the Obama administration than they deserve credit for. My sense would be that when the Syrian civil war began, without thinking through what he was doing, the president made his remarks about “Assad must go” with no appreciation for the implications of that kind of a statement. He didn’t appreciate how difficult dislodging Assad was going to be. So the president’s rhetoric was way out in front of his willingness to act. My sense is that in the utter confusion of the Syrian civil war, where the anti–Assad forces came in various stripes and colors, combined with the emergence of ISIS as a force determined to overturn the regional political order, there was a period of confusion about what the United States should do. My sense is that today the administration has established a pretty clear priority, and the priority is to focus on the destruction of ISIS and worry about Syria somewhere down the road.

That said, mustering the military wherewithal to deal with ISIS has turned out to be a far more difficult proposition than the Obama administration anticipated, I think. The president’s determination to limit U.S. military exposure—no boots on the ground to avoid large-scale U.S. combat, even though there are boots on the ground—has then given the campaign a particular shape. We’re using considerable amounts of air power against an enemy that is not particularly vulnerable to air power, and combining this with an effort to train local forces. This has produced very mixed results. Particularly with regard to the regular Iraqi army, it has resulted in a campaign that’s not been particularly distinguished or successful.

We’re just sort of muddling along. So here you and I are speaking and the president has announced another 250 trainers, this little, minute escalation, as if it’s going to produce different results. You have to wonder how such small muscle movements are going to have big results.

I want to stay with the matter of America’s declared good intentions as it explains its conduct abroad. Accounts of our idealistic purposes—and our intentions are always cast in the service of our ideals—carry weight with many, many millions of Americans. From my point of view, to be honest, I can’t remember a time in my life when I took this kind of talk very seriously. The record simply doesn’t support it. Now I have a chance to ask a professional soldier about this and I can’t pass up the chance.

Well, I think that the moral arguments for U.S. policy, particularly moral arguments for the use of force, are added after the decision to go to war, to use force, has been made. The explanations for why we use our military power are rarely, if ever, informed by any serious moral consideration.

So they’re a coat of paint applied afterward.

A coat of paint is a very good explanation. There are those who might cite the Libya intervention of 2011 as an exception. To the extent that the triumvirate of [Secretary of State] Clinton, Rice [Susan, national security adviser] and [U.N. ambassador] Samantha Power were driving the train, I don’t doubt that they were genuinely concerned about the possibility of large numbers of Libyan opposition forces and individuals being killed by Gaddafi. But I’d also suggest that the Libyan intervention was supposed to validate this whole conception of “R2P,” the responsibility to protect. It didn’t, but had it done so, then, in effect, the validation of R2P would have created new opportunities for the U.S. to intervene wherever it wished to, citing R2P as a basis for action. So even there, where the proponents of policy may have had some amount of genuine humanitarian concern, I think there were secondary factors that looked beyond moral considerations.

In your book you divide the last 36 years into four phases. The fourth is now characterized under President Obama as an abandonment of “invade and occupy.” And the components of strategy you list are special operations, drone warfare, proxies and, I would add, bombing campaigns. To me it’s weakness across the board. There are problems in each one of these dimensions. Do you think this phase will endure for a long time? Where are we in it—the beginning, middle or end? And what in the world could be next?

I suspect it’s going to endure for a while, absent some sort of catastrophe that shifts public thinking about the use of force. It will endure for a while because the George W. Bush approach, “invade and occupy,” simply does not command public support. So those who are proponents of using military power find that the option of large numbers of boots on the ground is not politically viable, and therefore they more into this arena of trying to experiment with alternative methods. The emphasis on special operations forces or drones or, as you just suggested, air power more broadly, provides ways to use power without the risks and costs of large-scale involvement of ground forces.

I don’t see that changing all that much. When you listen to some of the hawkish remarks coming from the presidential candidates—take Ted Cruz and what he would do—I don’t believe he has said, “Elect me president and I will invade Iraq.” Rather, he has said, “Elect me president and we’ll bomb the hell out of them and see if the sand can glow.”

Trump, too, in his posturing, has been rather explicit that we’re not going to be involved in long, drawn out campaigns. But he’s certainly not suggesting that he’s going to be resistant with regard to using American military power. He’s also going to hammer them. In his foreign policy speech [delivered in Washington April 27], he put ISIS on notice that their imminent destruction awaits his ascent to the presidency. But again, I don’t think it’s through an invasion type of scenario. My guess is that the Iraq syndrome—if that’s what we want to call it; I think we can call it that—is likely to have a considerable life.

I’m going to disagree with you on a point you made in the book concerning Obama and his “red line” in Syria and his allegations that Assad crossed it with a chemical weapons attack in August of 2013. I found that incident suspect from the first. U.N. inspectors arrived the previous day at Assad’s invitation to inspect the chemical weapons situation, and then he mounts a chemical weapons attack right in Damascus? It reeked from the outset. I find the evidence since then, coming primarily from Seymour Hersh’s investigations, fairly persuasive: That attack was a provocation by a rebel militia supplied by Turkey precisely to draw the U.S. across its red line. You don’t seem to buy that and I wonder why.

I just haven’t seen the evidence. I’m not questioning the logic and the possibility, by no means am I doing that. In that case, I’m accepting at face value what the official story was.

I don’t. My larger question is about the information pool. When we’re talking about all sorts of things having to do with the War for the Greater Middle East, most intensely now Syria’s situation, it is very, very hard to write with confidence about very much. Speaking as a hack of nearly 40 years, the information pool is very polluted.

You mean you don’t know who to believe.

Yes. I don’t necessarily believe anything I read in the New York Times. I’m 66 years old. I wouldn’t have said that 20-odd years ago. I worked for them. How seriously bad do you think the information coming over is, as it relates to the War for the Greater Middle East?

You made a point at the beginning of this conversation about the absence of historical context in daily reporting, and I think that’s a really important point. The story we get when we watch the nightly news or read the New York Times is a story shorn of historical context. It seems to me that we can cite that as a failing in the way the reporting of events occurs.

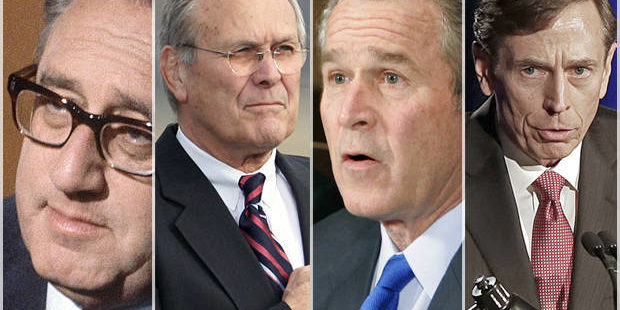

But to the larger point, it seems to me that the record is mixed. The consensus of opinion, I think, is that the press’s response to the George W. Bush administration’s effort to build a case for invading Iraq in 2002 was abysmal—that things were taken at face value, that Judith Miller was functioning as a propagandist for the administration. It was appalling, and helped to suppress any serious political debate over whether or not that war made sense. That said, as it became apparent that the promises of an easy victory were not going to be fulfilled, that U.S. forces were indeed embroiled in one hell of a mess, I think I would say that reporting was pretty good at identifying the factors and forces that were operative in this civil war/insurgency/jihad. I think the press did a pretty good job. You don’t?

No, I don’t. I think they leave out very large dimensions of the story. With intent, I should add.

To oversimplify, in the run-up to the war there was a lot of cheerleading, and once we were in the war it seemed to me that the cheerleading stopped pretty quickly.

If you mean sort of Ernie Pyle-level stuff, OK. But that’s not my concern. I call it in my columns, “the power of leaving out.” We have forests worth of stuff on the Islamic State, I can’t put a number on it, but very few efforts to explore questions of causality, responsibility, agency, action and reaction. We don’t get any of that.

I would agree with that. I was talking more in terms of: When it was obvious that we were stuck in a mess, the press said, “This is a mess.” It did not accept the line coming out of the White House that the light at the end of the tunnel was clearly visible, or that some particular event in Iraq marked a turning point—an election or a constitution; there were so many turning points that you started to get dizzy.

The press, I think, was appropriately skeptical of those claims of progress, and therefore did educate the American people that the Iraq war was a mess. The evidence of that is not immediate, but by 2006 the Democrats win both houses—basically a reflection of anti-war sentiment, at that moment at least, in the Democratic Party. Rumsfeld gets fired. It took a while, but I think the press gets some amount of credit for educating the American people.

Your book includes chapters on the Balkan “diversion,” as you call it. I think it would be useful for you to describe how these events in the 1990s are stitched into a book about the War for the Greater Middle East.

A friend of mine who read the manuscript said I was going to get hammered on this by everybody. My real response is: If a reader finds it implausible to include Bosnia and Kosovo in the Greater Middle East, skip those chapters. But I think it is plausible.

Are the Balkans part of the Greater Middle East? In the book I say, well, Mexico is both in North America and is part of Latin America. And I think the Balkans are emphatically part of Europe, but they’re also part of the Greater Middle East. Historically, that’s been the frontline, in a way, between the West and the Islamic world. There’s a large residual Muslim population in both Bosnia and Kosovo—in Kosovo it’s a majority—and this religious identity was a major cause of the violence in both Bosnia and Kosovo. And to at least some degree, but not entirely, I believe the rationale for U.S. intervention was the expectation that intervening on behalf of beleaguered Muslims would somehow contribute to a more favorable standing on the part of the United States in the eyes of Muslims elsewhere. That last part didn’t happen, but that was the expectation.

This question is hypothetical, but it came to me several times as I read the book. I said to myself, “Andrew, take it all away.” Start again in 1979 or 1980. Brzezinski never said all those things to encourage Carter. He never talked about military preponderance. What could have happened instead of what has? What was or is the alternative to the War for the Greater Middle East? And what would have been needed for this to happen?

Well, to me, that’s why the so-called “malaise speech” [Carter’s address urging a national self-examination, July 15, 1979] is so interesting. Because Carter outlined an alternative path. Carter invited Americans to rethink, in the most fundamental way, what it means to be a free human being.

For you it begins with our consciousness of ourselves. I couldn’t agree more.