Who will Biden bomb first?

The President-elect’s ‘global leadership’ is a return to the failed policies of Obama and Clinton

This article first appeared on Unherd on December 4, 2020.

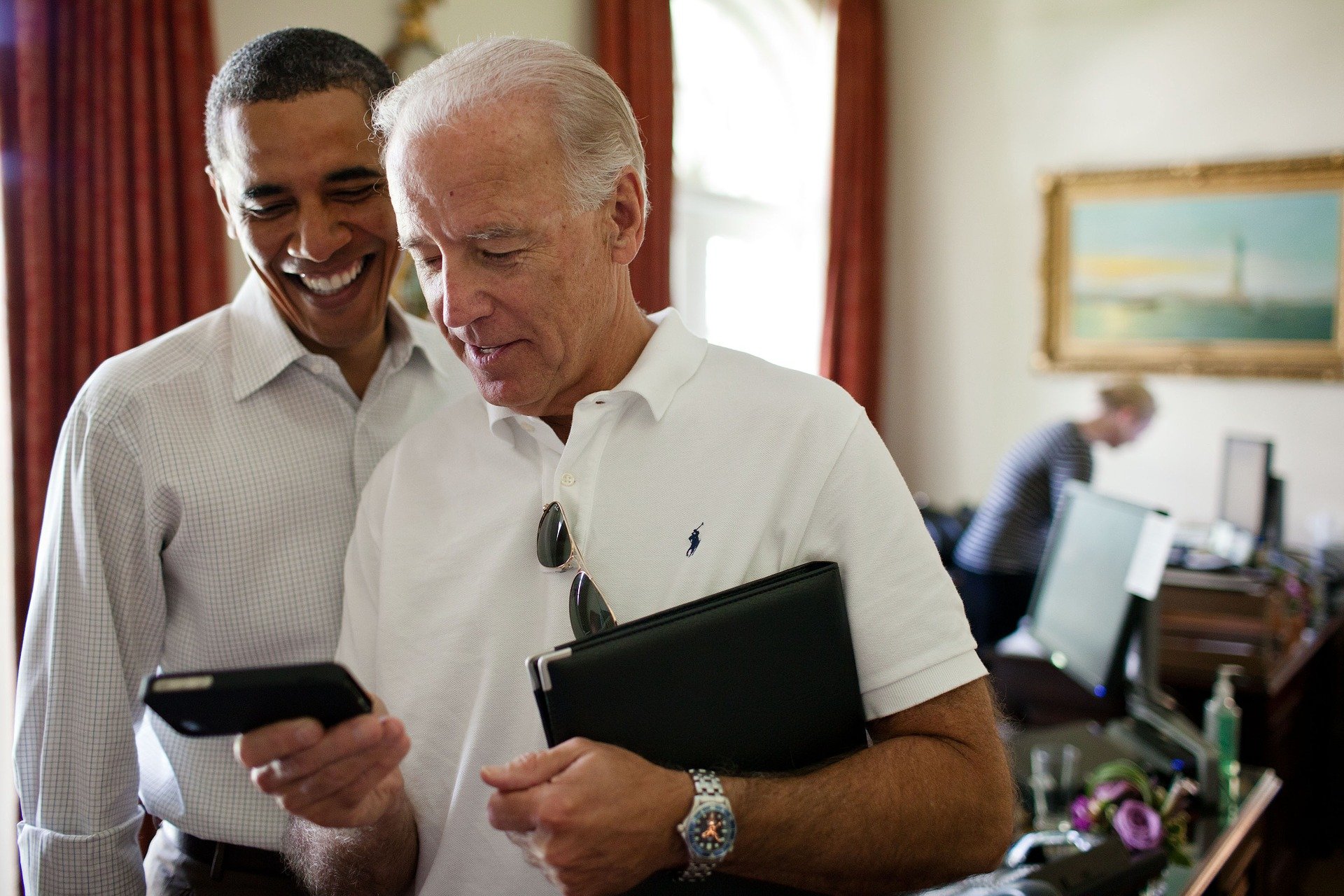

“America is back.” So President-elect Biden declared after announcing his cabinet nominations last week, and after the Trump presidency many around the world will at least be relieved that normality has returned. But global joy might be short-lived, because with the new White House appointments, there is no longer any mistaking what we are in for these next four years. Joe Biden is a restorationist, evidently intent on giving America and the rest of the world as faithful a copy of the Obama administration as he can conjure. It might be truer to say that American exceptionalism is back.

All was well before Donald Trump came along and all shall be well again now he is gone. This is the product Biden has on offer, but it is shoddy goods on two counts: all was not well before Trump took the White House, and all will not be well if, as Biden’s appointments indicate rather clearly, our forty-sixth president insists on pretending our forty-fourth had it all right.

Diversity is de rigueur as Biden shapes his administration. He promises “the most diverse cabinet in history,” and his nominees so far are indeed dense with women and people of colour, just as former Obama Secretary of State Hillary Clinton played the diversity card during her 2016 campaign, naming women, black people, Asian-Americans, Hispanics and others to high office.

But now as then, it is diversity of identity that is supposed to count, not diversity of thought, of which one finds none among Biden’s newly-named people. This is a sales job, just as Barack Obama was a salesman — window dressing for an un-pretty foreign policy regime.

And there shall be no diversity among nations, either, as Joe Biden fashions his post-Trump idea of America’s proper place in the world. On this side of the pond, there are headlines about Team Biden’s abiding intention to use foreign policy to reconnect with the global community. “Biden Picks Team Set on Fortifying World Alliances,” The New York Times announced atop page one last week while Democracy Now!, a Democratic Party-aligned radio programme, puts it this way: “Biden’s National Security Appointments Focus on Multilateralism, International Cooperation.”

We Americans love these multisyllabic words. And we love making them mean other than what one finds in our Merriam–Webster dictionary.

The lately prevailing theme — multipolarity, alliances, partnerships, shared responsibilities — is also to be traced back to the earliest days of the Obama administration. The most important of Biden’s newly-announced cabinet and advisory appointments — respectively Antony Blinken to State, Jake Sullivan as national security adviser — sound it routinely: We cannot solve the world’s problems alone, they say with solemn conviction.

It is an excellent thought, as it was first time round. But we had better look carefully at who these people are — both Obama administration holdovers — and listen carefully to what they say. The alliances-and-partnerships bit did not turn out well when Obama tried it, and there is nothing to suggest that, four years on, it will work this time round.

The first thing to note about the administration Biden is introducing to the world is never mentioned in the American press, and certainly not among the foreign policy cliques. Biden’s people are to a man and woman American exceptionalists — true believers in the country’s providentially-conferred destiny to light humanity’s way. There is nothing new or remarkable in this: our chosen-people consciousness goes back to Winthrop’s “City on a Hill” sermon, delivered before the celebrated Puritan set out from Southampton for these parts in 1630.

But as long as this credenda goes unquestioned, nobody is going to change the direction of American foreign policy in a way that responds imaginatively to the realities of the 21st century. Chief among these is parity among nations, notably those of the West and non–West.

To put this question in a useful context, one of Donald Trump’s supposed original sins, committed during his presidential campaign in 2016, was his full-frontal disavowal of our exceptionalist ideology. “I don’t like the term, I’ll be honest with you,” he told a Texas audience. “I don’t think it’s a very nice term: ‘We’re exceptional, you’re not.’” Three years later, when the fight to defeat Trump’s re-election bid was fully joined, the man now named Biden’s national security adviser published a spirited argument “for rescuing the idea of American exceptionalism” in The Atlantic. Jake Sullivan’s was “a case for a new American exceptionalism… as the basis for American leadership in the twenty-first century”.

All that flows from the White House, the State Department, the Pentagon and the national security apparatus over the next four years will reflect this belief. But how does one reconcile all the talk of partnerships and common cause with “global leadership,” another of the Biden people’s running themes? When the next president declares that “America is back,” you have to read into the statement to grasp the true meaning: “It’s a team that reflects the fact that America is back. Ready to lead the world, not retreat from it. Once again, sit at the head of the table.”

America has long required enemies to maintain its spot at the “head of the table”, the Cold War being the case nearest to hand. So far as one can make out, China and Russia, America’s twin Beelzebubs, are to serve as the Biden administration’s primary organising principles. To be noted in this connection: Strategic rivalries with the Chinese and Russians were the primary topic at a NATO foreign ministers meeting in Brussels this week, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo’s last before Blinken replaces him.

Blinken and Sullivan are now preparing to enlist the Europeans, India and numerous East Asian nations as the U.S. conjures a new and dangerous Cold War with China. This is, of course, a straight-out continuation of the ultra-hawkish Pompeo’s cause. But Pompeo hasn’t got very far and neither will Team Biden. None of the Asians, not even the ever-loyal Japanese and certainly not congenitally non-aligned India, wants anything to do with an animated anti–Chinese coalition. Even Taiwan does not want confrontation; it wants protection. None of these countries desire to turn the region into another decades-long flashpoint.

It is now confirmed that Biden will extend the new START accord with Russia, due to expire early next year. This is wise, and one hopes Biden will go further on nuclear-arms reductions. But to the president-elect’s people this is an arms-control question, not a matter of U.S–Russian relations. These will not improve because Biden’s national security team are packed with Russophobes (including Joe himself). Antony Blinken, whose father was a noted advocate of détente, is vigorously of the view that ties with Russia can be repaired only if Moscow accepts unequal relations in which Washington sets the terms. Bill Clinton tried the same thing to no avail. Ditto Barack Obama.

Will the Europeans re-enlist in this front in the new Cold War? One seriously doubts it. If Trump’s four years made anything clear in trans–Atlantic relations, it is that the continent no longer wishes to be force-marched into another of Washington’s anti–Russian crusades. Emmanuel Macron has been consistently outspoken on this point over the past couple of years. It is true the French president nurses a de Gaulle complex, but he is simply more forthright than others in expressing what is on a lot of European minds.

It was commonly assumed until last week that, along with the Paris climate pact and the WHO, Biden would also bring America back into the many-sided accord governing Iran’s nuclear programs. The assassination last Friday of Dr. Mohsen Fakhrizadeh complicates things, but it was highly questionable whether Biden and Blinken would have made the move even if Iran’s top nuclear researcher hadn’t been murdered (almost certainly by Mossad). Biden, like almost all other American pols, is simply too close to Israel, which has made its objections to the nuclear agreement abundantly, belligerently clear.

So we’ve now got Sullivan saying “yes, we’ll get back in with other signatories — providing Tehran meets ‘these follow-on agreements’” — which are understood to be an awful lot like Pompeo’s preconditions, please note. This is an intended-to-fail position — and an easy way out for Biden. Net outcome: hostile stalemate in the Persian Gulf, continuing alienation from the European signatories to the accord, more trans–Atlantic drift.

If only America’s leaders understood that, with the emergence of new powers such as China and India and a new generation of post–Cold War leaders in Europe, ours is an age that requires us to accept — no, embrace — a diversity of perspectives. But our policy cliques, lost in nostalgia, travelling on presumption, and with no decisions to make for the past 75 years, simply cannot read the hands on the clock.

Biden’s “global leadership” will be the same as all previous versions — a polite term for American hegemony. Sullivan, Blinken and Biden’s other national security nominees may put themselves forward as vigorous proponents of partnerships, but look closely: they expect America’s allies to fall in line behind America’s we-know-best dictates. Apostles of exceptionalism can think no other way.

However, the tousle- haired turnip who “leads” the UK will fall smartly in line even before the line has been drawn.

America is not actually “back” as it has never left. The wildly ignorant gibberish of the short Trump experience was but a slight glitch in the long timeline of criminal war, genocide and general murder of anyone or anything that got in the way of our exceptional attempt to plunder the entire planet. The concept of “America” as a democracy with liberty and justice for all is a shopworn farcical bit of carnival barking. We i. e., the United States of America, are in reality the perfect example of a Continuing Criminal Enterprise, U.S.Criminal Code Section 848. We’ve been running opium and heroin out of Afghanistan for about twenty years now under the pathetically transparent guise of “fighting terrorism” while it is us who are the actual terrorists. If you cannot see this obvious and blatant fact, no need for you to do anything other than cheer Joe Biden on. We got nations to plunder, dope to run and bombs to drop and we ain’t got time to fiddle around with diplomacy and stuff like that!