THE REVELATIONS OF WIKILEAKS: No. 7— Crimes Revealed at Guantánamo Bay

“Gitmo Files” lifted the Pentagon’s lid on the prison, describing a corrupt system of military detention resting on torture, coerced testimony and “intelligence” manipulated to justify abuses at the base, writes Patrick Lawrence.

Today we continue our series The Revelations of WikiLeaks less than three months before the extradition hearing for imprisoned WikiLeaks publisher Julian Assange resumes in Britain. This is the seventh in a series of articles that is looking back on the major works of the publication that has altered the world since its founding in 2006. The series is an effort to counter mainstream media coverage, which these days largely ignores WikiLeaks’ work, and instead focuses on Assange’s personality. It is WikiLeaks’ uncovering of governments’ crimes and corruption that set the U.S. after Assange, ultimately leading to his arrest on April 11 last year and his indictment under the U.S. Espionage Act.

The Anatomy of a Colossal Crime

Perpetrated by the U.S. Government

WikiLeaks released a cache of classified documents on April 25, 2011, it called “Gitmo Files.” They consist of reports the Joint Task Force at Guantánamo Bay sent to the Southern Command in Miami, under which JTF–Gitmo had imprisoned and interrogated suspected terrorists since January 2002, four months after the Sept. 11 attacks in New York and Washington.

These memoranda, known as Detainee Assessment Briefs, or DABs, were written from 2002 to 2008. They contain JTF–Gitmo’s detailed judgments as to whether a prisoner should remain in prison or be released either to his home government or to a third country. Of the 779 prisoners detained at Guantánamo at its post–Sept. 11 peak, “Gitmo Files” is comprised of DABs on 765 of them. None had previously been made public. As was WikiLeaks’ practice, it gave numerous news organizations access to “Gitmo Files” at the time of publication.

Prior to the WikiLeaks release, very little was known about the prison operation at the U.S. naval base on the southeastern coast of Cuba. In 2006, in response to a Freedom of Information suit filed by The Associated Press four years earlier, the Pentagon made public transcripts of military court hearings held at Guantánamo Bay. While these revealed the identities of some detainees for the first time, they contained little detail of how those imprisoned were treated, interrogated, and then judged.

“Gitmo Files” thus lifted the lid on a Defense Department operation that had been shrouded in secrecy for the previous nine years. They describe a profoundly corrupt system of military detention and interrogation that rested on torture, coerced testimony, and “intelligence” manipulated to justify the military’s practices at the Guantánamo base.

“Most of these documents reveal accounts of incompetence familiar to those who have studied Guantánamo closely,” wrote Andy Worthington, a WikiLeaks associate who managed the publisher’s analysis of the documents, “with innocent men detained by mistake (or because the U.S. was offering substantial bounties to its allies for al–Qaeda or Taliban suspects), and numerous insignificant Taliban conscripts from Afghanistan and Pakistan.” Worthington called the 765 documents WikiLeaks published “the anatomy of a colossal crime perpetrated by the U.S. government.”

Obama’s First Term

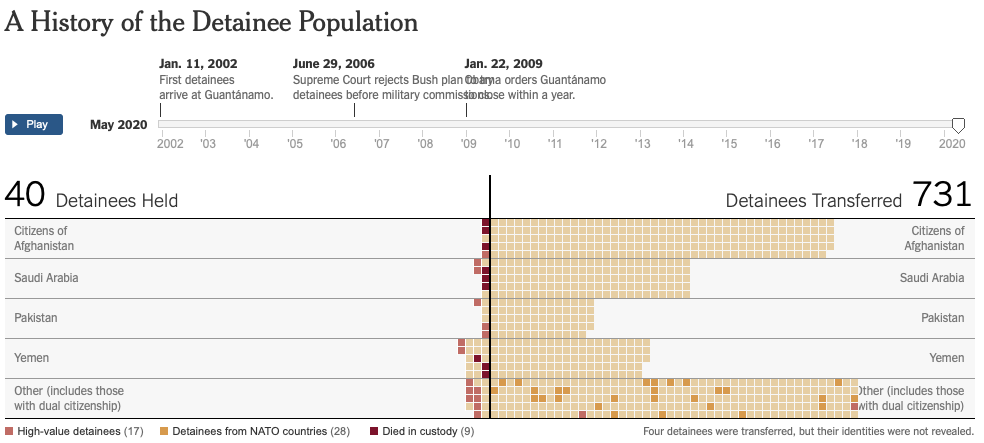

Barack Obama had begun his first term as president slightly more than two years before WikiLeaks published “Gitmo Files.” During his political campaign he had promised to close the facility within a year of assuming office; at that time 241 prisoners were still in detention. An interagency Guantánamo Review Task Force Obama appointed to review these cases concluded that only 36 could be prosecuted.

But Obama succumbed to “the politics of fear in Congress,” as Worthington puts it. There were still 171 prisoners when “Gitmo Files” was published; 40 now remain — some cleared and awaiting release, some charged and awaiting military trial, some convicted, and others, 26 of the total, under indefinite detention.

The Documents

The memoranda collected in “Gitmo Files” shine a revealing light into the U.S. military’s system of arrest, detention, and interrogation of terror suspects after the Sept. 11 tragedies. The files include the DABs covering the first 201 prisoners released from Guantánamo, between 2002 and 2004. Nothing had previously been known about these detainees. The military briefs on these cases recount the histories of innocent Afghans, Pakistanis, and others — a baker, a mechanic, former students, kitchen workers — who should never have been detained in the first place.

These early-release detainees were among the easiest to identify as posing low or no security risks. Their stories reflect the indiscriminate method of arrests U.S. forces used immediately after the Sept. 11 attacks. “Gitmo Files” terms these detainees “The Unknown Prisoners of Guantánamo” because no record of their presence at Gitmo had been made public prior to the April 2011 release.

They were effectively “disappeared” — unacknowledged detainees — apparently because their patent innocence was an embarrassment for the Pentagon and, especially, those operating the Guantánamo prison.

Azizullah Asekzai was one of these early-release detainees. He was a family farmer in his early twenties when the Taliban conscripted him to fight its cause in Afghanistan. After one day of training on an AK–47, Asekzai attempted to escape to Kabul, but a local militia ambushed the vehicle he was traveling in and Asekzai was captured. He was subsequently turned over to U.S. forces; he was transferred to Guantánamo in June 2002.

Asekzai’s DAB explains his transfer thus:

The detainee was arrested and transported to Bamian, where he was imprisoned for almost five months before being transferred to U.S. forces. Detainee was subsequently transported to Guantánamo Bay Naval Base because of his knowledge of a Taliban draftee holding area in Konduz and of Mullah Mir Hamza, a Taliban official, in Gereshk District of Helmand Province. Joint Task Force Guantánamo considers the information obtained from him and about him as neither valuable nor tactically exploitable. [Italics added.]

Asekzai’s DAB is dated March 2003, and he was released the following July. While his time at Guantánamo was relatively brief, his story is important because of the light it sheds on how those writing DABs manipulated the facts in case after case to mask what amounted to a dragnet method of arrests in Afghanistan. In Asekzai’s case, as in many others, this meant making up the military’s motives to obscure the groundless basis for his detention and transfer to Guantánamo.

Here is an explanatory comment Wikileaks included with its “Unknown Prisoners” files:

The “Reasons for Transfer” included in the documents, which have been repeatedly cited by media outlets as an explanation of why the prisoners were transferred to Guantánamo, are, in fact, lies that were grafted onto the prisoners’ files after their arrival at Guantánamo. This is because, contrary to the impression given in the files, no significant screening process took place before the prisoners’ transfer[s]…. Every prisoner who ended up in U.S. custody had to be sent to Guantánamo, even though the majority were not even seized by U.S. forces, but were seized by their Afghan and Pakistani allies at a time when substantial bounty payments for “al–Qaeda and Taliban suspects” were widespread.

These bounty payments were not limited to small-time Afghan or Pakistani bounty hunters. In his 2006 memoir, “In the Line of Fire,” Pervez Musharrif, Pakistan’s former president, acknowledges that in handing over 369 terror suspects to the U.S., the Pakistani government “earned bounty payments totaling millions of dollars.”

“Gitmo Files” also includes a section on the 22 children also detained at Guantánamo after it opened. Three were still in detention at the time of the WikiLeaks release. In addition, the documents detail the cases of the 399 prisoners released from 2004 to the day “Gitmo Files” was published. They also give the background of the seven men who had died at Guantánamo by April 2011.

Each DAB is signed by the Guantánamo commander at the time of the report. While they included JTF–Gitmo’s assessment and recommendation for each prisoner, the disposition of each case was determined at a higher level. In addition to the judgments of JTF–Gitmo, the DABs also reflect the work of the Criminal Investigation Task Force, the post–Sept. 11 Pentagon agency created to conduct interrogations, and the “behavior science teams,” or BSCTs.

These were the now-infamous psychologists who participated in the “exploitation” of prisoners during interrogations — in many cases condoning the use of waterboarding and other forms of torture.

JTF–Gitmo’s standard practice was to present each DAB in nine sections. These begin with a detainee’s identity and personal background and run to his health, the detainee’s account of events, an evaluation of this account, and the JTF–Gitmo assessment and recommendation of each case. Worthington has scrutinized each of these sections in the DABs to unearth information that might otherwise remain obscured. On the section covering the health of detainees, for instance, he writes, “Many are judged to be in good health, but there are some shocking examples of prisoners with severe mental and/or physical problems.”

‘Capture Information’

In the sections labeled “capture information,” the DABs report how and where each prisoner was apprehended, the date of his transfer to Guantánamo, and the above-noted “reasons for transfer.” Worthington terms these last accounts “spurious,” offering this explanation: “The reason that this is unconvincing is because… the U.S. high command, based in Camp Doha, Kuwait, stipulated that every prisoner who ended up in U.S. custody had to be transferred to Guantánamo — and that there were no exceptions.”

This is why those writing DABs found it necessary to doctor the reasons for transfer, “as an attempt to justify the largely random rounding-up of prisoners,” as Worthington puts it.

The last section of a DAB is called “EC status” and explains whether or not a detainee is still considered an “enemy combatant.” These judgments are based on military tribunals held at Guantánamo in 2004–05. Worthington writes, “Out of 558 cases, just 38 prisoners were assessed as being ‘no longer enemy combatants,’ and in some cases, when the result went in the prisoners’ favor, the military convened new panels until it got the desired result.”

Worthington’s work on “Gitmo Files” is key to an adequate understanding of the 765 DABs covered in the WikiLeaks release. Read on their own, the military’s briefs appear to be routine bureaucratic accounts of the processing of each prisoner. But as Worthington explains, these documents are essentially whitewashes that often obscure more than they reveal. As noted, explanations of the intelligence used to justify the prisoners’ detention were often concocted and inserted into a prisoner’s record after he was arrested and sent to Guantánamo.

Ghost Prisoners

Another significant flaw Worthington identifies is the JTF–Gitmo’s repeated use of the same witnesses to testify against numerous prisoners — in the case of one witness, 60 of them. Worthington identifies many of these repeat witnesses as “high-value detainees,” or “ghost prisoners,” in Guantánamo parlance, and details their histories in confinement.

As he explains,

“The documents draw on the testimony of witnesses—in most cases, the prisoners’ fellow prisoners—whose words are unreliable, either because they were subjected to torture or other forms of coercion (sometimes not in Guantánamo, but in secret prisons run by the CIA), or because they provided false statements to secure better treatment in Guantánamo.”

Equally important, in many of the DABs — perhaps most of them — it is difficult to detect the prisoners’ true histories, which in the majority of cases reveal their innocence and the injustice of their imprisonment. This is why Worthington’s work on “Gitmo Files” was an essential part of WikiLeaks’ method. He spent long months analyzing the documents; in some cases, Worthington found and interviewed released detainees to get their accurate accounts of events on the record. He then wrote a lengthy series of articles explaining his findings.

These voluminous writings are featured prominently on the “Gitmo Files” website. They are effectively a gateway into the inventory of the DABs that comprise “Gitmo Files.” Worthington’s “Unknown Prisoners” report comprises a 10–part series of articles. Worthington’s work, including his book, “The Guantánamo Files,” is noted in his introductory essays for each of the categories he uses to classify Guantánamo detainees.

Another of these categories, titled “Abandoned in Guantánamo,” concerns the 89 Yemenis still in detention at Guantánamo when “Gitmo Files” was published—more than half of those remaining. President Obama’s Guantánamo Review Task Force, named in 2009, recommended that 36 Yemenis be released immediately and 30 others be held in “conditional detention” until Yemen’s security situation improved.

As Worthington notes, most of the Yemenis remained in prison at the time he wrote. Of those Yemenis still in detention, 28 had already been cleared for release. Of them, six had been “approved for transfer,” as the task force put it, as early as 2004, three more in 2006, and 10 in 2007.

Gitmo Files” details the cases of 19 Yemenis still detained in 2011. Most of these were assessed as low-ranking Taliban or Al Qaeda infantry soldiers of no “intelligence value.” Saeed Hatim (known in his DAB as Said Muhammad Salih Hatim), was among these 19. Born in 1976, Hatim began studying law in Sanaa in 1998. After two years he dropped out to care for his ailing father. Here is a portion of Hatim’s own account as written into his DAB:

“Detainee was concerned by Russia’s war in Chechnya after he witnessed the ‘oppression’ [of the Muslims] on television. Detainee was ‘outraged’ about what the Russians were doing to the Chechens, and decided to travel to Chechnya to fight jihad alongside his Muslim ‘brothers.’ Detainee informed his family of his decision to travel to Chechnya and they refused to provide financial assistance. Detainee then spoke with several of his friends and members of his mosque, who agreed to help detainee raise money for the trip. Detainee left for Afghanistan in approximately March 2001.”

Hatim’s DAB says he admitted that Al Qaeda recruited him after his time in Chechnya. He purportedly fought U.S. forces in a major battle in the Afghan mountains at the end of 2001. JTF–Gitmo assessed Hatim as a “medium risk,” but it classified him as a “low threat from a detention perspective” and of low intelligence value.

Hatim was first recommended for release in January 2007. He was similarly recommended a year later; a habeas corpus petition his attorney subsequently filed was granted in 2009. That judgment was vacated shortly before “Gitmo Files” was released in 2011.

Here is the relevant portion of Worthington’s report and analysis of the Hatim case:

“In Saeed Hatim’s case… Judge Ricardo Urbina ruled out self-incriminating statements made by Hatim himself, accepting that he made them while being mistreated and threatened with torture in Kandahar after his capture, and also that he repeated them at Guantánamo ‘because he feared that he would be punished if he changed his story.’ “

Judge Urbina also ruled out the government’s major claim against Hatim — that he had taken part in a showdown between Al Qaeda and U.S. forces in Afghanistan’s Tora Bora mountains in December 2001 — because the only source for that claim was one of the notoriously unreliable witnesses identified in the WikiLeaks documents, who, in Judge Urbina’s words, “has exhibited an ongoing pattern of severe psychological problems while detained at Gitmo.”

Quoting an interrogator, the judge also noted that hospital records at Guantánamo said the witness against Hatim “had ‘vague auditory hallucinations’ and that his symptoms were consistent with a ‘depressive disorder, psychosis, post-traumatic stress, and a severe personality disorder.’” The interrogator concluded by “refus[ing] to credit what is arguably the government’s most serious allegation in this case based solely on one statement, made years after the events in question, by an individual whose grasp on reality appears to have been tenuous at best.”

US Officials React

Official reactions to the release of “Gitmo Files” were by and large predictable. The Obama administration’s statement, released by Geoff Morrell, the Pentagon press secretary, and Daniel Fried, Obama’s special envoy on detainee issues, asserted, “It is unfortunate that several news organizations have made the decision to publish numerous documents obtained illegally by WikiLeaks concerning the Guantánamo detention facility.”

Referring to Obama and George W. Bush, his predecessor, Morrell and Fried also said, “Both administrations have made the protection of American citizens the top priority and we are concerned that the disclosure of these documents could be damaging to those efforts.”

Significantly, there is no record of the president’s response to the release.

The Pentagon came under special criticism with the Gitmo release’s revelation of the detention of 22 children at Guantánamo. As Worthington explains, in May 2008 the Pentagon had reported to the U.N. Committee on the Rights of the Child that it had held only eight juveniles (those under 18 when their alleged transgressions took place) since Guantánamo began receiving detainees in 2002.

Worthington took the occasion to elaborate on the “Gitmo Files” disclosure. In his commentary he wrote: “My new research coincides with a new report by the UC Davis Center for the Study of Human Rights in the Americas, ‘Guantánamo’s Children: The WikiLeaked Testimonies,’ drawing on the release, by WikiLeaks, of classified military documents shedding new light on the prisoners, identifying 15 juveniles, and suggesting that six others, born in 1984 or 1985, and arriving at Guantánamo in 2002 or 2003, may have been under 18, depending on when exactly they were born (which is unknown, as it is in the cases of numerous Guantánamo prisoners).”

In total, Worthington asserted, the number of children imprisoned at Guantánamo may have been as many as 28.

Like the president, the Pentagon remained silent on this question after Gitmo Files was published. There is no record of a Defense Department response to the WikiLeaks disclosures concerning children and Worthington’s analysis of them.

In April 2019 — eight years after “Gitmo Files” was published — military courts continued to grapple with the record of events, specifically the use of torture, during the post–Sept. 11 “war on terror.”

In a report datelined April 5, 2019 The New York Times explained,

“Seventeen-and-a-half years after the Sept. 11, 2001, terror attacks, and a decade after President Barack Obama ordered the C.I.A. to dismantle any remnants of its global prison network, the military commission system is still wrestling with how to handle evidence of what the United States did to the Qaeda suspects it held at C.I.A. black sites. While the topic of torture can now be discussed in open court, there is still a dispute about how evidence of it can be gathered and used in the proceedings at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba.”

This week the Justice Department filed a new indictment against Assange, superseding that filed in May 2019 and broadening the charges lodged against him last year. This is the most recent official reaction to “Gitmo Files.” This latest indictment, presented in the Eastern Virginia District Court and dated June 24, alleges that Chelsea Manning produced “Gitmo Files” at Assange’s urging between November 2009 and May 2010. In keeping with WikiLeaks’ most fundamental principle, it has never disclosed the source of “Gitmo Files.” Neither has Manning stated that she was the source, although this has been widely considered as likely.

Proving that Assange actively solicited the documents Manning passed to WikiLeaks—“Collateral Murder,” “Afghan War Diary,” “Iraq War Logs,” and now, allegedly, “Gitmo Files”—is key to the U.S. case against Assange under the Espionage Act.

The June 24 court document indicates that the Justice Department has no hard evidence of this charge. Manning continues to assert, as she has since her arrest in May 2010, that she acted of her own volition in gathering and dispatching the documents WikiLeaks published. The indictment alleges only that Manning, in assembling what became “Gitmo Files,” used certain search phrases—“detainee+abuse,” for example—that the indictment identifies with WikiLeaks’ categorization of documents—an allegation far short of accepted standards of proof.

Press Reaction

On the “Gitmo Files” home page, WikiLeaks names 10 “partners” with which it worked in making the documents public. Worthington is listed as one, though his work puts him in a category of his own. The others include The Washington Post, The Telegraph, La Repubblica, Le Monde, and Der Spiegel. These news outlets were given copies of “Gitmo Files” in advance to allow them time to review and analyze the documents and plan their coverage prior to the April 25, 2011, release.

Conspicuously missing from this WikiLeaks list, and reflecting a prior dispute they had with Julian Assange, are The New York Times and The Guardian. Both newspapers obtained the documents from a source other than WikiLeaks, presumably one of the news outlets on the WikiLeaks list of partners. To its credit, The Times now maintains a web site, The Guantánamo Docket giving the name and legal status of each detainee still in custody at Guantánamo.

The noteworthy aspect of the media coverage of the “Gitmo Files” release was the marked difference in the way U.S. and non–American news outlets shaped their stories: U.S. media tended to emphasize the dangers and threats presented by those in captivity at Guantánamo; other media reported correctly that among the important revelations in “Gitmo Files” was the innocence of most of those seized and detained.

Noting this pattern, WikiLeaks urged readers and viewers to compare the lead paragraphs in the main BBC and CNN stories:

The BBC, under the headline, “WikiLeaks: Many at Guantánamo ‘not dangerous,’” reported, “Files obtained by the website WikiLeaks have revealed that the U.S. believed many of those held at Guantánamo Bay were innocent or only low-level operatives.”

CNN’s report appeared under the headline, “Military documents reveal details about Guantánamo detainees, al–Qaeda,” and began, “Nearly 800 classified U.S. military documents obtained by WikiLeaks reveal extraordinary details about the alleged terrorist activities of al–Qaeda operatives captured and housed at the U.S. Navy’s detention facility in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba.”

Among the others to note this disparity were Glenn Greenwald, then the foreign affairs columnist at Salon, and Laura Flanders at The Nation. Greenwald’s piece on the news coverage of “Gitmo Files” appeared under the headline, “Newly Leaked Documents Show the Ongoing Travesty of Guantánamo” but is no longer available in the Salon archives.

Flanders detected the same bias in the coverage published by The Washington Post, National Public Radio, and the Times. The latter two “use the cop-out term ‘harsh interrogation techniques,’” she noted, to avoid mention of the word torture.

“So the takeaway in the United States,” Flanders wrote, “will remain ‘dangerous terrorists!’ and Guantánamo will most likely remain open three years after the president vowed to close it, while overseas the rest of the world will continue to wonder why the country that claims to love freedom so much is continuing to imprison and torture innocent people.”

In one of the essays WikiLeaks published with “Gitmo Files,” Worthington analyzed the broader significance of the tilt in American coverage. He wrote:

“The release of the documents prompted international interest for a week, until it was arranged by President Obama (whether coincidentally or not) for U.S. Special Forces to fly into Pakistan to assassinate Osama bin Laden. At this point an unprincipled narrative emerged in the mainstream media in the U.S., in which, for sales and ratings if nothing else, unindicted criminals from the Bush administration — and their vociferous supporters in Congress, in newspaper columns, and on the airwaves — were allowed to suggest that the use of torture had led to locating bin Laden (it hadn’t, although some information had apparently come from “high-value detainees” held in secret CIA prisons, but not as a result of torture), and that the existence of Guantánamo had also proved invaluable in tracking down the al-Qaeda chief.”