“The precarity election.”

Democrats ignored the working class once again.

Given Joe Biden’s pitifully narrow margin of victory last week, the 2020 election hardly represented the vaunted “blue wave” predicted by many pollsters. Give or take a shift of 100,000 votes or so in a few key Rust Belt and Sun Belt states, the most striking takeaway from the 2020 result is how much it mirrored the profound splits of the 2016 election. And despite the Democrats’ incessant charges of racism, more than a quarter of Donald Trump’s votes came from nonwhite Americans—the highest percentage for a GOP presidential candidate since 1960.

This may seem strange until one realizes that economic precarity—the elephant in the room neither party addresses with any seriousness—transcends issues of ethnicity, gender, and race for most Americans other than the identity politics set. This has to rank among the truths 2020 has just driven home, and one can hardly be surprised: The economic uncertainty and vulnerability that blight the lives of millions of Americans (and others, for that matter) remain hallmarks of contemporary capitalism. Automation, globalization, and cuts in social programs have led to widespread economic instability among ordinary citizens—men and women, young and old, black and white, skilled and unskilled, middle class and poor alike.

The obvious challenge is to build a more stable, secure, and sustainable society, which means explicitly addressing the issue of gross economic inequality as we find across the United States. But inequality is only part of the problem. That is a symptom of the broader issue of economic insecurity—which leaves an increasing majority of our population living in persistent anxiety over the costs of health, housing, education, and a corresponding collapse in self-confidence and aspiration.

It will be interesting to watch the Biden administration in this connection, but the outlook is far from encouraging. Biden looks like nothing more than a change-at-the-margin pol—as he and his people have taken to telling voters, indeed, now that victory is theirs.

Some Democrats still champion themselves the party of the working class, though this, truly, is “without evidence” at this point. Most don’t even bother with the pretense. Until the party more credibly addresses the causes of our economic malaise as opposed to its symptoms, blue waves are unlikely to be more than occasional blue ripples.

https://twitter.com/davidsirota/status/1324005093918666754

As the Democratic Party abandons the working class, so now does the working class seem to abandon the Democrats. The latter encourage a focus on social justice, race, and gender-related questions—worthy enough concerns but pointless when treated in isolation from the issue of income and wealth and the economic stability these considerations determine. In truth, identity politics is nothing more than a distraction when separated from the question of power—which is precisely the leadership’s point, one strongly suspects. In turn, this focus alienates a working class whose shift toward social conservatism has long been evident—these, “the deplorables,” as Hillary Clinton put it in a rare moment of honesty four years ago.

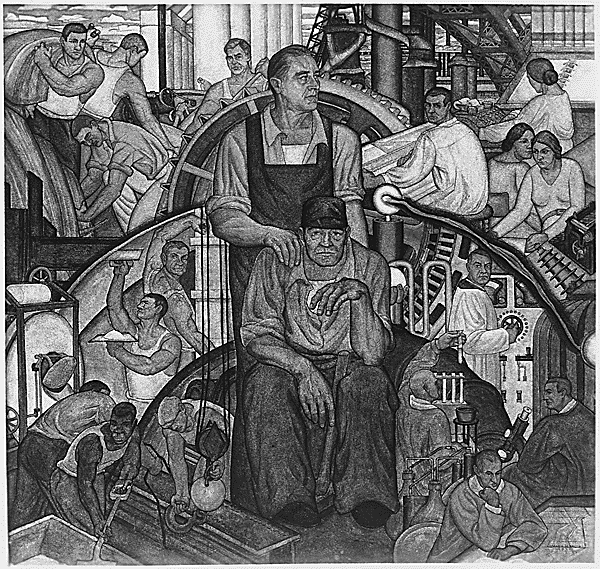

Those New Deal days when Democrats stood for strongly blue-collar policies are long gone now and, by all evidence, will never return. The mainstream of the party, not to mention the identitarians, are supremely indifferent to the grievances of wage-earners today, notably but not only their anxieties and deprivations in the matters of health care, housing, education, the quality of public services, and job security. As is well known, in many instances Democratic Party policies—not least those Joe Biden has sponsored—have exacerbated these problems, a straight-out consequence of their quasi-religious adherence to neoliberal ideologies.

Case in point is California’s just-passed Proposition 22, a neo-feudal piece of legislation from the bluest of blue states that, in sanctioning the exploitations of the “gig economy,” leaves a large chunk of the state’s workers in a state of insecurity by undermining traditional employee protections and benefits that exist in California’s existing labor law.

The Golden State has long been viewed as a leading indicator of future social, economic, and political trends. This goes back to 1978, when the infamous Proposition 13 (a property tax-cutting provision) prefigured Reagan’s supply-side fiscal policy two years later. If it is still true that “as California goes, so goes the country,” then today’s economic precariat ought to be very concerned about the ratification of Proposition 22, a regressive union-busting measure that allows Uber and Lyft to continue classifying their drivers as contractors, not employees, thereby exempting them from a California labor law that seeks to outlaw the practice.

Is Prop 22 to Biden what Prop 13 was to Reagan? There’s more than a passing argument for the thought.

Although both Joe Biden and Kamala Harris explicitly opposed Prop 22, it certainly didn’t help the Democrats’ messaging that Kamala Harris’s brother-in-law and advisor, Tony West, led the campaign in favor of Prop 22; her niece, Meena Harris, works on Uber’s diversity and inclusion team. Now that California’s labor laws have been gutted, workers at gig economy firms will continue to be classified as contractors, without access to employee rights such as minimum wage, unemployment benefits, and health insurance. No doubt, other states (and oligarchs) will take note.

This kind of mixed messaging could create an opening for the GOP, as Missouri Senator Josh Hawley just recently has recognized: “Republicans in Washington are going to have a very hard time processing this. But the future is clear: We must be a working class party, not a Wall Street party.”

Fighting words from this aspiring populist, but at the same time, if the Republicans are to become a more broadly based multiracial party of blue-collar conservatism, as Hawley (and Marco Rubio) desire, they will have to understand that what constitutes blue collar—work, life, existence, identity—is quite different from the 20th century blue collar of the old Democratic coalition and is going to be even more different in 10 or 20 years.

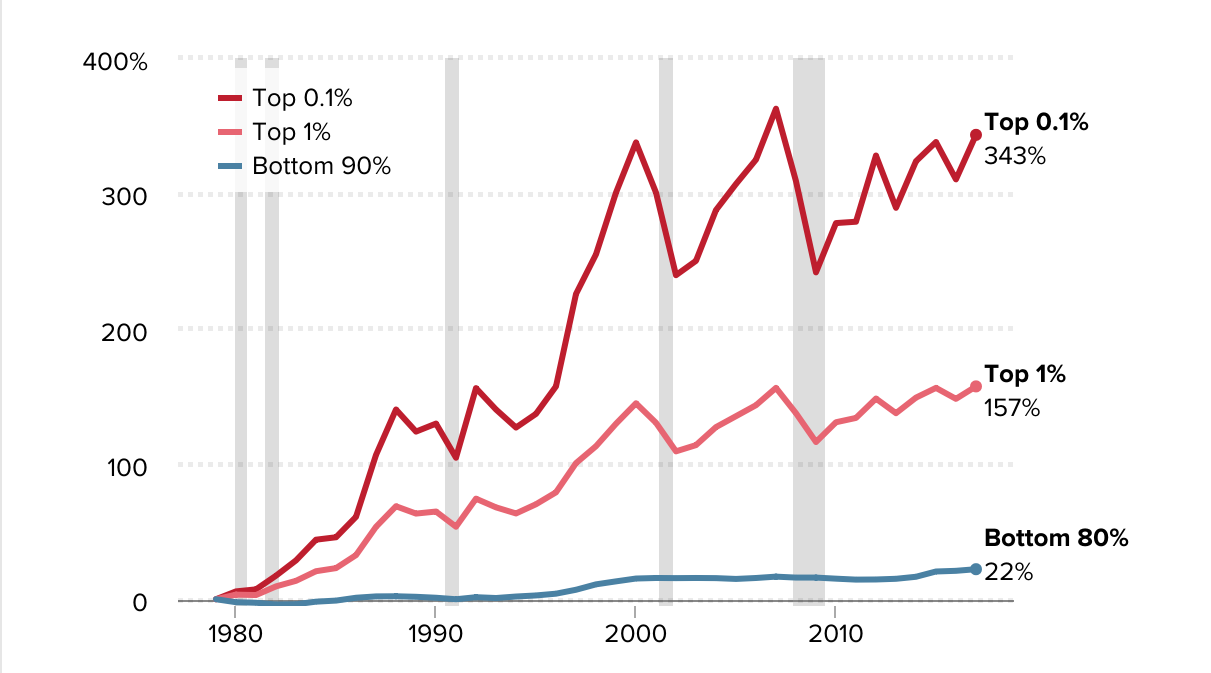

The march of inequality.

There are some recent indications that the GOP is beginning to grasp this. But the party still needs to consider reversing many policies that have long been part of its orthodoxy, notably supply-side tax policies heavily biased to society’s top earners and the ongoing support of “right to work” laws. Along with a tolerance of outsourcing production to low-cost labor jurisdictions, these policies have eroded labor’s position and accentuated economic inequality and insecurity.

The reality for both parties is that the working class as we knew it is disappearing—eviscerated through a combination of automation, globalization, attacks on private-sector unions, and cuts in public services. And until our political class comes to a broader recognition that work is nothing like what it was, and increasingly won’t be, it will be hard for either party to offer credible solutions. As things stand, our corrupt two-party duopoly makes a credible third party virtually inconceivable.

The last two elections manifest a country that is profoundly divided, with the economic precariat being the most profound and collateral damage. The GOP talks about security in militaristic terms or via guns and religion but seldom addresses economic insecurity. The Democrats claim an interest in redistributing income to alleviate the worst aspects of economic insecurity, but they resist the structural changes that gave rise to the problems in the first place. Until the precariat’s longstanding economic concerns—jobs, health, safety, pollution, government that serves the public, and above all, relative stability and employment security over long periods of time—are addressed, the U.S. will remain a profoundly divided and divisive country at war with itself.

Albena Azmanova: Associate Professor of Politics at the Brussels School of International Studies , University of Kent, author of Capitalism on Edge: How Fighting Precarity Can Achieve Radical Change Without Crisis or Utopia (2020).