“The great realignment II.”

Populism and its enemies.

This is the second of our two-part series on the ongoing American political realignment. In Part I we explored the historic backdrop of these momentous shifts. Here we consider alternatives to the neoliberal/fusionist consensus that has defined our political economy since the end of the Cold War, making a forecast as to the form a new emerging political consensus might take a few years hence.

Specifically, we query the emerging consensus that the Democratic Party will be at the forefront of this realignment in the wake of the 2020 election results and make the case that the Republican Party might well be better positioned to capitalize on the impending realignment.

Part I can be read here.

“Populism” is a term that, since the modern era began, has generally been trotted out to mean a political attitude that reflects widespread anger and resentment against powerful elites. Among press stenographers for the powerful, “populism” has been reflexively marshaled to warn against the passions and wants of the mob. Who uses this term and projects it onto the endless array of evolving political constituencies tells us a lot about our political moment.

During the financial crises of the post–Reconstruction era, “populism” was a term embraced by reformers and democratically minded movements that argued for universal social programs and public-interest regulation at the federal and state levels. By contrast, in the early part of this century, we saw populism crudely used to describe the nationalist counter-politics that emerged in response to the European integration process, from Italy to Hungary to Poland. More recently in the U.S. a cohort of leading conservatives has increasingly adopted the term as part of a wider sales pitch to seize on the steady disintegration of the working-class bloc that underwrote Democratic Party power and politics from FDR to the end of the Clinton years.

At the commencement of the Trump era, blue-collar/Red State Trump voters were often labeled populists. Likewise, Trump’s message and political aesthetics. But in practice, Trump rarely followed through on his rhetoric: His landmark legislation was a tax law that massively enriched the very swamp he had promised to drain. And the much-vaunted “get tough” on China trade policy achieved very little in terms of inducing additional re-domiciling of American manufacturing, or indeed, reducing Washington’s chronic trade deficit with Beijing.

Consequently, ascribing a principled populist credo to Trump—a.k.a. “Trumpism without Trump”—is a slogan too far. It sounds catchy, but it’s problematic for several reasons, not the least because the president’s incompetence and inconsistent policy positions on a host of issues make mockery of the idea that “Trumpism” in any way has constituted a coherent governing philosophy. While rhetorically attacking globalization, free trade, and international financiers, in actual policy terms Trump did little to genuinely advance the interests of workers, let alone cement them as a featured part of a broad new governing coalition of the Republican Party. The present-day reality is that the real political force of gravity is a matter of proximity to economic precarity, which reflects the abandonment and betrayal of the Democratic Party’s working– and middle-class voters.

Certainly, the circumstances are ripe for a major voting-bloc shift: Over the past 30 years or so, the Democratic Party has largely become a prisoner of the finance and tech industries and showed limited signs of shifting its focus during the presidential primaries in 2020. (To the extent reforms were embraced, they were seen chiefly through the prisms of gender and race, rather than class.) Biden won the 2020 election, but the shifting results could be ascribed more to changes in a few wealthy zip codes, as opposed to the appropriation of a key constituency that turned the race in favor of one party over another.

Consider the analysis of Darel E. Paul, a professor of political science at Williams College, who found that in the three largest states (Georgia, Michigan, Pennsylvania) that Biden was able to flip from Red to Blue this year, his margin of victory was owed to less to historic Democratic Party supporters, and more to do with the voters in the wealthiest suburban districts of Atlanta, Detroit, and Philadelphia. Down ballot, things were not quite as rosy for the Democrats. Republicans were able to capture fourteen seats previously held by Democratic incumbents, including those in the some of the poorest districts in the country, including Minnesota’s 7th, New Mexico’s 2nd, and California’s 21st.

Given this, it clearly doesn’t follow that the Democratic Party intrinsically remains the natural repository for a principled populist movement from the Left. And while it is true that Biden won 7 million more votes than Trump, it is also true that he won after the unmitigated disaster of Trump’s response to the Covic–19 crisis—which. as of this writing, has infected more than 17 million and taken more than 311,000 American lives. And Biden’s victory did not come with much of a coat-tail effect. Consequently, Democrats might do well to consider whether it was 2016 or 2020 that was the real aberration.

By the same token, the Republican Party is genuinely more ideologically unsettled today than at any time since Reagan’s election, commentator Eric Levitz has noted. Yet while conceding that figures such as Senator Josh Hawley have recently made common cause on a host of issues with leading progressives such as Alexandria Ocasio–Cortez, Levitz nonetheless argues that this group’s embrace of economic heterodoxy will invariably be constrained by powerful corporate interests within the GOP.

Donor-class pressures are often cited as reasons to doubt the GOP’s capacity to evolve in this direction. But this ignores the fact that equally strong donor-class considerations exist in the Democratic Party. As Michael Lind has observed, both Republican and Democratic Administrations have catered chiefly to the interests “not of domestic manufacturers and parts suppliers but of Wall Street (seeking to liberalize foreign financial systems), Silicon Valley and Hollywood and pharma (seeking more intellectual-property protection through trade treaties), and U.S. agribusiness, which by its nature cannot be outsourced and which can flourish even in a deindustrialized, weak U.S.”

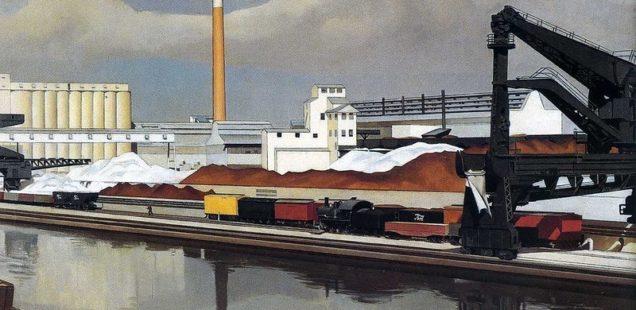

In that regard, the structural vulnerabilities exposed via the Covid–19 pandemic should inspire American policymakers to fix these shortcomings, notably by supporting necessary industrial renewal in the United States, as well as assuring that the country’s national-security interests are well safeguarded. That doesn’t reflexively mean funding another multi-billion-dollar weapons system for the Pentagon. Rather it is a question of economic security: minimizing reliance on foreign nations for procurement capacity for key materials and more broadly addressing the issue of gaps in global supply chains and America’s corresponding dependence on them, precisely to avoid future military conflict in response to these vulnerabilities.

The economic nationalism of the populist right seems curiously retrograde in a world of ever-expanding global interconnectedness, where it has become an axiomatic belief that a more open and interconnected world will be a better world. But the downsides of such interconnectedness have been conveniently ignored by globalization’s leading advocates, especially among Democrats who purport to represent America’s common men and women but who instead have become complicit in tolerating the evisceration of the country’s manufacturing core via incessant outsourcing to China and other parts of the world. Many dismiss advocates of a revived American industrial renaissance as impractical nostalgists who are unrealistically embracing an unsustainable autarky, all the while ignoring the lost economic competitiveness and skilled-job losses that have occurred because of existing policies.

Melding a national reindustrialization policy to national-security considerations is precisely the kind of policy marriage that makes it easier to keep a party’s oligarchs in line. It addresses a key point of contention among those who contend that the Republicans remain constrained by their party’s historic corporate interests, such as the libertarian Koch family and others whose funding priorities have historically been hostile to unionization, minimum wages, increased voting rights, and which favor the privatization of popular entitlement programs such as Social Security. That is all true, but it is worth recalling that several Republicans are geopolitical hawks first and market libertarians a distant second. Many increasingly see that it is nonsensical to make war on American wage-earners while claiming to protect the same wage-earners from Chinese competition, especially as Beijing becomes the locus of an emerging Cold War 2.0. Geopolitical competition, and even war, has historically encouraged national mobilization, consistent with broader public patriotism.

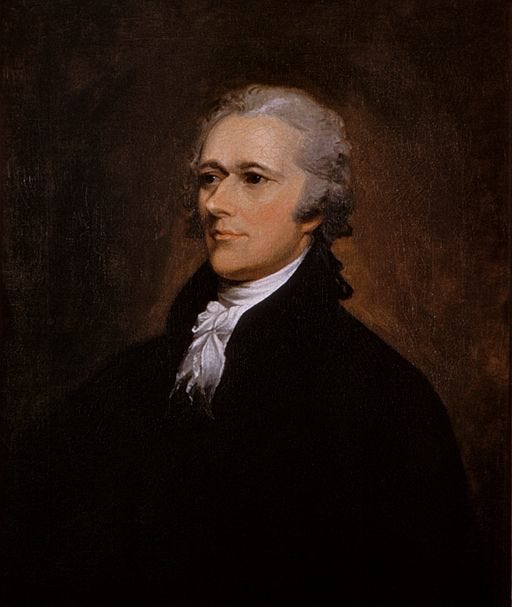

As counterintuitive as it may seem, a lack of geopolitical rivalry makes it hard to sustain a populism characterized by anti-elitism, because in such circumstances the rich can become antisocial monsters with no fear of punishment for putting profit considerations ahead of national security. By contrast, national developmentalism coheres with national-security objectives, as Alexander Hamilton, the first U.S. secretary of the Treasury, argued in his Report on Manufactures, wherein he advocated a comprehensive strategy to make the U.S. “independent of foreign nations for military and other essential supplies.” Rather than sacrificing American workers’ livelihoods to the altar of globalization, national developmentalism could and should be combined with some sort of German-style co-determination or sectoral bargaining with workers, leveling up regions that have missed out on most of the fruits of globalization over the past half century. A GOP donor class averse to workers’ rights might not flinch once it sees the long-term potential and stability that stems from these arrangements.

As recounted above, there seems to be a recognition among members of the Republican Party that the old way of doing business no longer serves the needs of their working– and middle-class constituents, particularly in light of the economic crisis brought about by the Covid–19 pandemic. The Republican Study Committee’s American Worker Task Force’s a new report, “Reclaiming the American Dream: Proposals to Empower the Workers of Today and Tomorrow”, has some promising ideas, notably in education where the authors place a renewed emphasis on Career and Technical Education to enhance domestic skilled labor, concomitant with lessening the emphasis on the one-size-fits-all university degree orientation of education policy today. This comes in conjunction with advancing alternative education routes and German-style apprenticeship programs to best match workers to the skill sets required to maximize employment opportunities in the 21st century economy. The paper also introduces the intriguing idea of “allowing workers to design non-traditional careers that fit their needs”. In this context, it is especially gratifying to see the GOP attack the “independent contractor” loophole that many companies in the gig economy have used to undercut traditional employee benefits.

But to truly “refocus labor policy to unleash the American worker” as the paper advocates, the Republican Party needs to consider a reversal of many policies that have long been part of its orthodoxy, notably supply side tax policies heavily biased to society’s top earners, the ongoing support of “right to work” laws on the labor front, along with a tolerance of American manufacturers’ proclivity to outsource production to low-cost labor jurisdictions, all of which have eroded labor’s position.

The Democratic Party Alternative?

How seriously can the Democratic Party, under a feckless neoliberal such as Joe Biden, be willing to return to a time-tested and successful Hamiltonian industrial strategy of using whatever means are necessary—tariffs, subsidies, local-content procurement, tax breaks, even overseas-development loans to countries that purchase U.S. manufactured exports—to ensure that strategic industries necessary to sustain U.S. national security interests (which transcend military considerations, but extend to vulnerabilities highlighted during the pandemic) are introduced to America or remain here?

To cite one obvious conflict, China has represented a longstanding gravy train to both high tech and Wall Street. Disrupting the “Chimerica” nexus would severely and profoundly damage these groups’ material interests. As for companies that are chartered in Ireland, hide their taxes via subsidiaries in Panama, and have 90 percent of their labor abroad, they should be banned from government contracts and treated as foreign entities, which in practical terms they are. If that means excluding Apple, so be it. That’s certainly going to create screams in Cupertino, but that should hardly be a concern of those wishing to promote a broad-based prosperity that included the millions who have until now been left behind. Given that we’ve spent trillions over the past two decades supporting capital markets and bailing out banks, an additional few trillion dollars to support technological superiority hardly seems an extravagant ask.

* * *

And so, if national conservatism of this sort represents one alternative, the social democracy of Bernie Sanders might have represented another, but for reasons that should be obvious, this alternative is nothing if not moribund within the Democratic Party in the wake of Biden’s convincing win among a crowded 2020 primary field. Indeed, the damage the Sanders loss to Biden in the Democratic primary did to progressive ideas, particularly those revolving around political economy, would be hard to overestimate.

Unfortunately, and perhaps unfairly, the Sanders insurgency will be remembered not for his articulation of how social democracy might benefit everyday Americans but more for the $220 million that his campaign operatives squandered with little to show for it; for Sanders’ supine inability or unwillingness to respond forcefully to Elizabeth Warren’s smear tactics; for his abandonment of his core economic message at the expense of his embrace of identity politics. Withal, the implosion of the Sanders campaign in 2020 doomed the chances of an actual social-democratic alternative within the party. Meanwhile, the reconstitution of the old status quo ante continues apace, as we can see in Biden’s cabinet choices, increasingly making 2021 look like the political equivalent of a rock concert comeback tour for the Obama Administration. Meantime, the Sanders wing of the party has been shunted off to the side, or worse, co-opted by the establishment.

For evidence of this look no further than Biden’s cabinet appointments. Not a card-carrying progressive among them. Or consider the impotence with which the progressives in Congress are currently displaying over their refusal to bring Medicare for All for a vote on the House floor for the (illusory) fear that doing so will somehow bring Kevin McCarthy to the speaker’s chair. But the inability of the Squad and Sanders to transform rhetoric into policy predates Biden’s victory. How many voted against the CARES Act, which facilitated the largest upward transfer of wealth in the country’s history?

As such, we believe the Democrats are in the process of losing one of the core constituencies of the FDR coalition: the blue collars. This isn’t to say that there haven’t been blue-collar defections from the Democratic Party in previous eras. But during the Nixon and Reagan years the defections were driven chiefly by blue-collar disgust with the social and/or foreign policy of the liberal elites. Today it is the neoliberal economic policies the Democrats are pursuing that are driving rust belt voters to the GOP.

One promising alternative to the neoliberalism of Biden–Harris would be a Galbraithian “Tripartism” that calls for the return of a 1950s-style settlement between the managerial elites and the working class. But the problem with hoping for such a settlement, as Notre Dame’s Patrick Deneen has pointed out, is that this assumes we have an elite that is interested in making a settlement. Better, perhaps, as Deneen recommends, that we seek a root-and-branch replacement of the current elite—one that reflects rest of the country, by which we mean socially conservative but economically liberal. An American version of what was once known as Blue Toryism in the U.K.

An emerging narrative increasingly sees Trump as a profound aberration, a transient expression of discontent. In fact, his presidency reflected an expression of broadly shared and lasting anxiety triggered by perceptions of (experienced or anticipated) physical insecurity, political disorder, cultural estrangement, and employment insecurity resulting from employment flexibilization, job outsourcing, or competition with immigrants for jobs. If the Biden administration, indeed the Democratic Party as a whole, fails to recognize that, it will continue to tend toward perpetual minority-party status in the country. Biden and the party need to embrace the revitalization and repurposing of the American public sector away from militarization to address the economy’s most pressing needs: rebuilding cities to make them safe, livable, and sustainable; guaranteeing jobs and incomes to the millions who provide services, education, and creating a viable public health infrastructure so as to avoid another invidious situation in which citizens are literally confronted with the choice of economic depression to offset the lack of public healthcare capacity to deal with future pandemics.

Historically in the U.S., there have been two kinds of developmental states: those based on government-industry collaboration, excluding workers, and those based on tripartite state-business-organized-labor “concertation”.

Or corporatism (in the social science sense).

The U.S. has had both. The Lincoln Republican developmental state was a government-industry alliance based on infant industry tariffs and subsidies to infrastructure (railroads). It was successful in rapid industrialization. But the National Guard suppressed strikes, the federal courts treated unions as conspiracies, and employers shipped in poor Europeans to drive down wages. Thanks to technology and increasing productivity, you did get some trickle down prosperity. But you also had palaces in Newport while workers in factories had to work six or seven days a week while being spied on by Pinkertons.

By contrast, the New Deal kept the Lincoln-to-Hoover developmental state, but incorporated organized labor (and farm organizations). So the lesson appears to be that without some sort of collective bargaining or corporatism or codetermination, the U.S. won’t get adequate pretax distribution of the gains from growth to workers, particularly if firms can offshore production and/or import immigrants in labor arbitrage schemes.

And without adequate pre-tax distribution in the form of high wages, the American political system will remain mired in a miasma of dysfunction and increasing corruption.