“Social media’s reckoning.”

Power in the wrong hands.

Tech companies, such as Twitter, Apple, and Facebook have been de-platforming President Donald Trump and his supporters at a rapid pace since the January 6th attack on the Capitol Building, much to the approval of the Democrats and much to the chagrin of the GOP (even though more than a few Republicans are beginning to change their minds about impeaching the President). No matter the nature of his departure from the White House, Trump’s “cancellation” raises several questions pertaining to censorship and the way in which we have regulated social media.

The bottom line is that there remain multiple routes to achieving some form of regulatory oversight. But the status quo is unacceptable, and regulation certainly should not be subcontracted to already hugely powerful tech behemoths that dominate social media. It is beyond ironic that members of the punditocracy and Congress, who have long decried Donald Trump’s authoritarian tendencies, would in turn laud Silicon Valley’s illiberal exercise of power in a manner evocative of a right-wing strongman.

True, the social media platforms are private companies. And while the First Amendment affords protection against government limits on Americans’ freedom of expression, it does not prevent a private employer from setting its own rules. It was intended simply to stop the government from punishing people for their opinions. But the First Amendment does not mean that Google, Amazon, or Twitter—or, indeed, The New York Times—has an obligation to publish those opinions.

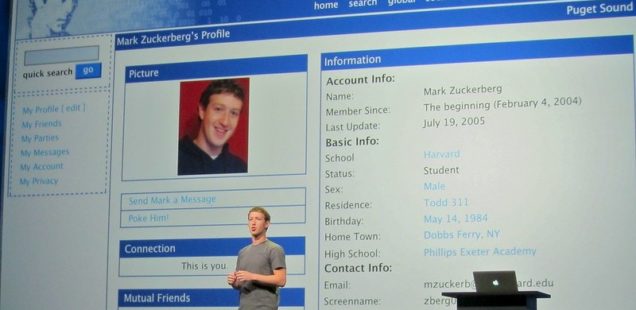

In that narrow sense, Jack Dorsey, Jeff Bezos, and Mark Zuckerberg, of Twitter, Amazon, and Facebook respectively, are well within their rights to de-platform a sitting president of the United States, shocking as the very thought may be. On the other hand, the social media platforms disseminate their content via the internet, which is a public good, and in this sense they should be subject to oversight and regulation, much as our conventional media companies are.

“Res Publica” means “public thing.” A republic presupposes both a public sector and public space, meaning, in turn, that we must preserve public “media” space and public media “oversight.” In Tom Paine’s time, “media” meant pamphlets, such as Common Sense. That was the 18th century. The 21st century equivalent includes spectrum and broadband.

Public spectrum and broadband must be publicly maintained and run. The First Amendment constrains how it is run; it does not provide an absolute right to freedom of expression. Specifically, it prohibits content-discrimination within the bounds of fundamental-rights-respecting deliberative democracy. Calls to ignore electoral results may well fall within the bounds of free speech, but incitement to political violence is not deliberative and may cross the line. So in that sense, the people now decrying “censorship” are in some ways barking up the wrong tree.

That does not mean that the social media companies get a free pass for the decision to shut down Donald Trump’s accounts. For one thing, Twitter, Facebook, and other social media platforms were more than happy to monetize Trump’s content for the past four years and made huge profits in the process. It is therefore more than a little galling today to see them discovering all their collective spine in the dying days of his presidency. For another, it is equally troublesome to see ostensibly progressive champions of free speech effectively begging our high-tech overlords to take on the job of judge, jury, and executioner, when this is clearly a job that Congress must arrogate to itself.

There may be no place in the digital public square for a neo–Nazi group. But that doesn’t resolve the problem once and for all. Having successfully induced Silicon Valley oligarchs to banish these retrograde groups to the fringes and expel various other right-wing extremist groups from their platforms, Democrats now find themselves in the enviable position of having Big Tech shape the range of acceptable free speech in a manner largely consonant with the party’s objectives and opinions but leaving no fingerprints at the scene of the crime.

Jack Dorsey or Jeff Bezos can conveniently de-platform and silence the Democratic Party’s adversaries. Social media therefore risks becoming the 21st century digital equivalent of Pravda, as it promulgated the Soviet Communist Party doctrine, to the exclusion of alternative opinion. Consequently, the Democrats now have huge political incentives to leave the Silicon Valley oligarchs alone.

That’s wrong. For one thing, it leaves too much power in Silicon Valley’s hands, with likely deleterious consequences ahead, much as the excessive free hand given to Wall Street’s financial engineers ultimately gave us the 2008 global finance crisis. Subcontract this kind of power to Big Tech and imagine what mischief might follow. Why arrest your political opponents when you can get corporations such as Google to cut off their phones, their bank accounts, and their electricity and water? You can claim that the state itself is not authoritarian and in a narrow sense this is true. But you can still see the potential scope for mischief when you empower Silicon Valley too much and allow them to determine what constitutes hate speech and what doesn’t, what incites violence and what doesn’t, what speech should be allowed and what shouldn’t, etc.

Twitter’s just-updated “Civic Integrity Policy” (highlighted the other day by Christian Christensen, a professor of journalism at Stockholm University) rather nobly (or frighteningly) promises to label or remove information “on how to participate in an election or other civic process.” Sounds anodyne enough: We don’t want misleading information out there that somehow diminishes voters’ participation in an election.

But the newly promulgated policy doesn’t stop there: Twitter goes on to suggest that such bans would extend to “misleading information intended to undermine public confidence in an election or other civic process.”

In the context of what happened on January 6th, that may sound reasonable. But let’s take a step back in time: Would this policy have included commentators who chose to question the outcome of the 2016 presidential election on the grounds that Russia engineered Trump’s victory? It’s easy enough to ban QAnon. Would Twitter’s new conduct policy extend to Max Boot or Jonathan Chait, two noted Russiagate proponents? Highly unlikely, given the extent to which virtually the entire American media and the Democratic Party itself lost their way amid an orgy of Russophobia.You can see the problem.

To the extent that Democrats have focused on the issue of regulating Big Tech, it has usually taken the form of “break’em up.” During Elizabeth Warren’s presidential campaign, for example, the Massachusetts senator made the case that tech companies acted as monopolies and needed to be cut down in size to promote more competitive markets, via traditional antitrust instruments such as the Sherman Act. The implicit premise was that increased competition via vigorous antitrust activity and more regulatory activism would spur additional innovation, as it levels the playing field between large and small businesses.

However, this is irrelevant to the issue of content regulation. Indeed, simply recreating “competitive” conditions by breaking up Twitter may lead to further dissemination of radical hate speech, as more media outlets respond to the increased competition in “the marketplace of ideas” by expanding the range of “acceptable” opinion. This is exactly what happened in the aftermath of the Federal Communications Commission’s decision to eliminate the so-called “fairness doctrine” in 1987. The repeal is said to have laid the foundations for the emergence of a multitude of hyper-partisan talk radio shows and, later, Fox News (although it is worth recalling that the fairness doctrine, as interpreted by the Supreme Court, required that speech be answered with more speech, and did not single out any one point of view as objectionable or off-limits).

There is also the issue of network effects, as Bloomberg columnist Noah Smith, has argued:

In the absence of any top-down efforts to break up Twitter, there will only be one Twitter—the value of a platform increases based on the number of other people on that platform. That force relentlessly pushes platforms to consolidate.

Smith’s point highlights another tension. It’s all fine and well to suggest that a “marketplace of ideas” will allow freedom of expression to flourish. But the network effects he highlights means that those ideas are curated (and ultimately limited) by a monopolistic platform, which undermines that marketplace. And who is to guarantee that our Big Tech overlords, who control this monopoly, will act in a totally disinterested manner? Was Parler, the alternative Twitter, removed from Google and Apple’s respective app shops (in effect, removing it from the internet as a result) because it disseminated hate speech, or because it was becoming a formidable competitor? However difficult it may be to achieve, there is no alternative to democratic oversight and effective regulation in the public interest, which is the job of Congress.

What should that regulation look like? Would the repeal of Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act do the trick?

Before he self-destructed politically, Senator Josh Hawley introduced the Ending Support for Internet Censorship Act, the aim being to narrow the scope of legal immunity conferred on large social media companies by Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act. Under Hawley’s proposals, Google, Twitter, Facebook, et al. would not be allowed arbitrarily to limit the range of political ideology available for the public’s consideration. The proposed legislation would also require the FTC to examine the algorithms as a condition of continuing to give these companies immunity under Section 230. Any change in the search engine algorithm would require pre-clearance from the FTC.

But Hawley’s rationale for introducing this legislation was to ensure the neutrality of the digital platforms so that all political viewpoints are adequately represented. Paradoxically, efforts to retain a platform’s political neutrality could well create disincentives against moderation and in fact encourage platforms to err on the side of extremism (which could well recreate the alarming conditions that we saw on January 6th).

Of course, even if Hawley’s reasoning for the bill’s introduction was mistaken, one could still argue that the social media platforms should be held liable on product-liability grounds because the dissemination of information led to the destructive behavior we saw at the Capitol Building last week. So long as Section 230 immunities exist, legally sanctioning the platforms is problematic, which effectively allows them to continue to make money as engines of radicalization and hate speech if they choose to do so.

There is a secondary problem related to Section 230: Its provisions have already been integrated into various international trade agreements, including the new USMCA agreement among the U.S., Mexico, and Canada and the bilateral trade agreement between the U.S. and Japan. This is also becoming a template for future trade agreements. Consequently, as David Daven, editor of The American Prospect, contended: “If the U.S. tries to alter Section 230, Facebook or Google could sue, maintaining that the proposed change, whatever it might be, was illegitimate and violated the USMCA.”

To be sure, this is a legal fight worth having, if only because it underscores the antidemocratic shackles now embedded in most “trade” agreements. And it may well a surmountable problem. However, there is little doubt that Section 230 provisions already incorporated into existing trade agreements are being established as a template for future trade deals. This represents an additional form of political-risk insurance on the part of the social media giants. It could well forestall regulatory attacks of the kinds increasingly being discussed in the halls of Congress.

There are other possible forms of regulation: Philip M. Napoli, a public policy professor at Duke, has conceded that “the FCC’s ability to regulate on behalf of the public interest is in many ways confined to the narrow context of broadcasting.”

Consequently, there would likely have to be some reimagination of the FCC’s concept of public interest to justify expanding its regulatory remit into the realm of social media. Napoli concludes that, given social media companies are significant aggregators of private user data,

If we understand aggregate user data as a public resource, then just as broadcast licensees must abide by public interest obligations in exchange for the privilege of monetizing the broadcast spectrum, so too should large digital platforms abide by public interest obligations in exchange for the privilege of monetizing our data.

Congress might laud the fact that Donald Trump has been “cancelled” and at writing appears headed toward a second impeachment. But that does not give its members the right to abrogate their constitutional responsibilities by sub-contracting the role of free-speech policeman to Big Tech. This dangerously empowers Silicon Valley further without necessarily addressing the problems thrown up by the events of last week. It’s perfectly acceptable to criticize Donald Trump’s affinity for right-wing authoritarians, but somehow when Mark Zuckerberg or Jack Dorsey behave this way in the service of an ostensibly “liberal” agenda, anything goes.