“The scope of our failure”: The real story of our decades-long foreign policy disaster that set the Middle East on fire

The brilliant Andrew Bacevich tells Salon why our massive march to folly in Middle East has to be seen as one war

I first interviewed Andrew Bacevich, the soldier turned scholar, after he spoke at the Hope Club, an old-line gents’ establishment in Providence, Rhode Island. That evening he outlined a dozen or so “theses,” as he called them in honor of the 95 Luther is said to have nailed to the door of the Wittenberg Castle Church in 1517. He was in essence reading a rough outline of the manuscript then on his desk. It was a powerful presentation, and we met again in a Boston restaurant to talk shortly thereafter. This was roughly a year ago.

The book Bacevich was drafting, “America’s War for the Greater Middle East: A Military History,” is now out. And as impressive as his synopsis of its themes was last year, the “dissident colonel,” as I like to call him, did not do this account anything close to justice. It is the first book to explain the Middle Eastern wars we have lived with for 36 years now as one unbroken conflict with many theaters. And it is scholarship of the best kind—carefully researched and referenced, but written with unscholarly grace—to put the point bluntly—and perfectly accessible to the intelligent general reader. You put it down thinking, “I understand a great deal more than I did when I started reading this.”

I drove to Boston last month to interview Bacevich again. When I arrived he was delivering a lecture to a gathering of faculty and students at the University of Massachusetts, Boston. He is emeritus now at Boston University but plainly still firing on all eight. This will not be his last book, he hinted, but it may be his last on the topics he has addressed in his others to date. These include “American Empire” (2002) “The New American Militarism (2005), “The Limits of Power (2008) and “Washington Rules” (2010).

It was interesting to hear Bacevich talk through the new book again, this time post-publication. He was, if anything, more forceful in his judgments of America’s Middle East failures. But this did not deter detractors and critics, I ought to add. During the Q & A afterward, he contended with one LaRouche adherent and one member of the Revolutionary Communist Party USA, whose questions were not quite questions so much as vehemently delivered challenges. I was struck by the courtesy and aplomb with which Bacevich responded—qualities I had seen in him when we met in Providence.

Afterward, we crossed a corner of the campus to the JFK Presidential Library, which sits on a rise overlooking Boston harbor. The spring wind out the building’s sea-facing wall of glass was brisk; gulls and geese wheeled just above the white caps as we spoke. As Bacevich was generous with his time and never other than interesting, I have broken the interview into two parts.

This is the first. The transcript was expertly produced by Salon’s Michael Conway Garofalo, who has my gratitude.

You’ve written a remarkable book. It’s original in treating the Middle East and surrounding regions as unitary in American strategic thinking since 1980. Yet you’ve done nothing more than examine readily available facts and records with the proper degree of intellectual detachment. To my knowledge, no one has treated the past 36 years as a single phenomenon. Am I wrong?

No, I think you’re correct. One of the aims of the book is to persuade Americans, persuade readers, that to consider U.S. military involvement in this part of the world as “one damn thing after another” is to miss the true significance of what we have been attempting to do and to misapprehend the scope of our failure. It’s a problem in our politics to focus on the most recent episode, the ongoing episode, and to ignore everything that came before.

There’s no past in Washington. There’s no past in the media. So the book’s an encouragement to self-understanding, in effect. But introducing historical perspective in these matters is like crashing a black mass with a crucifix, and I imagine your scholarly colleagues—those not ruined by ideology—approve. But what about your old army buddies and policy people on the inside?

All my old army buddies are long retired. And I have very, very few contacts in the active-duty force, in terms of personal connections. That said, I am encouraged by the number of emails I get from younger officers, people I’ve never met, who have now read this book or previous books or articles and express general support. My point here is that—and maybe this is wishful thinking on my part—I do sense there is something of an awakening in the officer corps, an awareness of how badly wrong we’ve gone. That awakening could lead to some critical thinking in military circles. Now, whether that would translate into political circles I don’t know. I find deeply troubling the absence of any serious critical thinking about our war, or wars if you wish, in the foreign policy establishment.

It’s astonishing. I’m never other than astonished by the shallowness of the thinking in the policy cliques.

Yes, astonishing. I mean there’s lots of debate, but it’s not a debate that takes the broad view, takes stock of how we got here.

You can move your needle one or two degrees either side of zero, in my read.Deviate further and you’re cut out of the loop.

Exactly right. So the debate ends up being: “Well, will bombing suffice to destroy ISIS?” or “Will we need boots on the ground?” I mean that’s about the extent of it.

I have to tell you a story. This happened right here, across the river in Cambridge. The daughter of a friend was at the Kennedy School [of Government, at Harvard] studying international relations, no mean accomplishment getting in. But she quit after a year. How come? All they ever want to talk about, she explained, is the military option. If you put any kind of paper forward that doesn’t begin with the military option, no one takes it seriously.

Isn’t that revealing?

Yeah. And that’s the Kennedy School.

Anyway, keeping in the historical vein, you draw a perfectly straight line from Truman’s “doctrine” speech, his “scare the hell out of the American people” address [delivered to Congress March 12, 1947] to Carter’s “doctrine” speech, which started the War for the Greater Middle East on January 23, 1980, and then Bush II’s “doctrine” of pre-emptive war, and then Obama’s assertions that the war in the Middle East was, as you put it, “redundant,” only to make enlarging our wars his chief contribution.

Are we required to conclude that a lot of very smart people are somehow incapable of learning anything at all from experience?

I actually think that Obama has learned from experience. In that now-famous Jeffrey Goldberg article [on Obama’s foreign-policy thinking, published in the Atlantic in March] it’s Goldberg allowing the president to speak, and I think the president is showing himself to be someone who over the past seven-plus years has actually acquired a very sophisticated understanding of statecraft and of the world as it is. When he became president he knew next to nothing about foreign policy. We routinely elect people to the presidency who know next to nothing about statecraft, but I think he’s learned a lot, and I found that to be very impressive.

That said, you would say, “Well if he’s learned so much then why don’t we see greater change than we see?” I think his presidency is a reminder to some degree as to the constraints under which presidents operate. There’s this fiction in our public discussion of politics that seems to imply that whoever is president is the dictator or the messiah, and that’s simply not true. They are constrained by the fact that there’re two other branches of the federal government. They’re constrained by the permanent national security apparatus. They’re constrained by history. They’re constrained by the fact that they inherit situations that they’re not able to wave their hand and make go away. They’re constrained by the actions and interests of other nations, some which profess to be allies, some of which are obviously not allies.

So I think we’re condemned to being disappointed by our presidents. Even if they come into office as people of good will, we’re condemned to be disappointed because we don’t appreciate the limits of their authority, and the limits of their freedom of action.

You mention that Truman had to “capitulate,” and then, similarly, Carter had to capitulate. When you say this, to what or to whom did they capitulate?

The Truman capitulation occurs in response to the beginning of the Korean War. I believe that until that point, Truman was still clinging to…

FDR’s vision of peaceful partnership [with the Soviet Union]?

…or of the United Nations becoming an entity that would prevent further conflicts after World War II. He also was resistant to the notion of creating a permanent, large U.S military establishment, to some degree because of his naivety, I think, about atomic weapons. Once the Korean War began, the capitulation was in agreeing to the conclusions contained in the famous document called NSC-68, which had been commissioned but had not been acted upon until after the North Koreans invaded the South. And the capitulation was to commit the United States to becoming a permanent military power. The permanent military power.

For which there was a considerable constituency?

Who was he capitulating to? He was capitulating to the then-emergent national security apparatus, consisting of senior military officers, the “four stars” [the joint chiefs of staff and other top generals], who had been adamant that the budgets that he was approving in ’46, ’47, ’48 were totally inadequate; but also capitulation to these new national security bureaucrats, who, for reasons not identical to those of the military, were also committed to maintaining, on a permanent basis, a large national security apparatus. The embodiment of those people at that particular moment was this guy Paul Nitze [a key figure in shaping Cold War policy during many administrations], who was the principal author of NSC-68—not the only example of that kind of a person but a very important example who was influential at the particular moment.

Carter’s capitulation was, in a sense, a capitulation to the American people. He had, in his “malaise” speech in the summer of ’79, called upon the people to change, to embrace a different definition of freedom, believing that if we embraced a different definition of freedom we would return to the path of virtue and would also be able to avoid getting drawn more deeply into the complex politics of the Persian Gulf. I think in January of 1980 he concedes that the American people are not going to change, not going to rethink our culture, not going to rethink what we believe is a satisfying way of life, and so the capitulation is to them.

And what is the capitulation about? The capitulation there is to add the Persian Gulf to the limited roster of places that we view as worth fighting for. And that we subsequently then do fight for, in ways large and small, albeit never yielding any particular success.

How do you parse and apportion the various drivers that make American policy what it is? I identify these as follows: Psychological—the insecurities Americans have nursed since the 18th century—and maybe the 17th ; ideological—our exceptionalism and universalism; material—the drive for markets and economic dominance—and strategic, which at this point amounts to a desire for global hegemony or something close to it. Do you have any others to add, and what is your read as to which are the most prominent?

I think you’re making a very important point, and that is that there is no single explanation. This is the problem, I think, of those who argue that it’s all about capitalism. Or people say it’s all the military-industrial complex. Or it’s all the state of Israel. It is all those factors that you cite, and I think I would add one more, and that would be domestic politics. The cycle of elections and the competition for political power, then, shapes the posturing that the campaigns elicit.

But your question was, how do they all stack up in terms of priorities? Well, this is where I subscribe to the argument that Niebuhr makes in “The Irony of American History.” [Reinhold Niebuhr, theologian and public-affairs commentator; the book was published in 1952.] As I understand the argument, at the root there is this conviction that we are uniquely called to be the agents of history. That history has a direction and a purpose and its destination is defined by who we are, and that we have some responsibility to bring history to this intended outcome. I think, by no means dismissing the influence of these other factors, that the dogged persistence of our behavior, even in the face of obvious failure, is rooted in our conviction that we are the instrument of Providence. And that goes all the way back to the founding of Anglo-America to John Winthrop’s “City Upon a Hill.”

Does your answer to that question change when you examine it in the context of Bush II’s presidency?

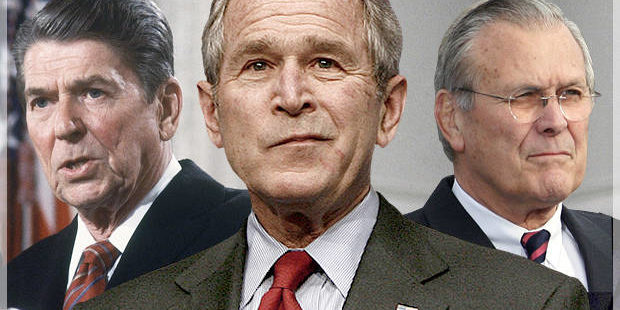

There is a slightly different answer. Maybe it’s sort of a variation on the theme, but my sense is that Bush and his inner circle were deeply influenced by their reading of the outcome of the Cold War, in three respects I think.

First is that the outcome of the Cold War marked a historical turning point of transcendent significance. Second, that the outcome of the Cold War affirmed the superiority of the American model—that liberal, democratic capitalism was indeed the only way. And third, that the end of the Cold War, combined with its immediate sequel, which was the Persian Gulf war of 1991, together demonstrated that the United States had achieved military supremacy and demonstrated the unprecedented utility of American military power, if policymakers simply had the guts to put that military power to work.