Pence’s Attacks on China Won’t Help Trump at G-20

Beijing wants to avoid an all-out trade war with Washington. That is what will count at the G-20 summit later this week, writes Patrick Lawrence, not the U.S. vice president’s hostility in Asia earlier this month.

Trying to Isolate China is a Failing U.S. Strategy

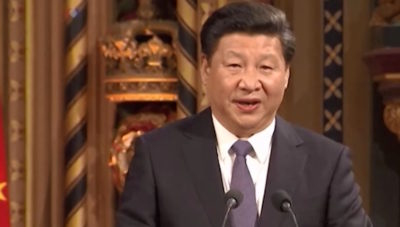

After Vice President Mike Pence’s poor reception in Asia a couple of weeks ago one shouldn’t expect a great outcome for President Donald Trump when he meets China’s President Xi Jinping at the Group of 20 summit in Buenos Aires on Friday.

Trump sent Pence to Asia earlier this month to deliver two bluntly hostile attacks on the Chinese and to insist that the rest of Asia choose: You’re with us or you’re with them.

U.S. officials have delivered many obtuse performances in Asia over the years, but Pence bested them when he spoke in Singapore at an annual summit of Southeast Asian nations and, two days later, at theAsia–Pacific Economic Cooperation session in Papua New Guinea.

In Singapore he cast China’s presence in the region as an “empire of aggression”—skipping the fact that China has no recent record of aggression. He then turned the 21–nation APEC session into a direct face-off with Xi, who was also present.

The U.S. vice president’s over-the-top performances were probably a case of calculated pugnacity; a softening-up exercise. But if they have any effect at all on Xi it will be to stiffen his position when he meets Trump later this week. Washington does not yet realize that challenging China’s place as an Asian power is a losing proposition.

The incipient trade war between the U.S. and China was one of Pence’s prominent themes. He threatened tomore than double the tariffs the Trump administration has already imposed on $250 billion worth of Chinese exports if China fails to fulfill Washington’s long list of market-opening measures. “The United States,” Pence said, “will not change course until China changes its ways.”

Attacks on ‘Belt and Road’

Pence’s most vituperative remarks at APEC concerned China’s immensely ambitious Belt and Road Initiative, intended to connect the Eurasian landmass from Shanghai to Lisbon via ports, power grids, rail lines and other infrastructure projects. Pence asserted the multi-trillion-dollar effort is nothing more than a debt trap structured to China’s advantage.

He then presented Asians with their neatly packaged us-or-them choice. “We don’t coerce or compromise your independence,” Pence said. “We do not offer a constricting belt or a one-way road,” he taunted. “When you partner with us, we partner with you, and we all prosper.”

It takes a lot of nerve, ignorance of history, or both, for an American official to make such assertions. U.S. banks and Western-controlled financial institutions such as the International Monetary Fund have made an art of saddling developing nations with debt—and dictating economic policies along with it—since the Bretton Woods system was negotiated in 1944. Remember the Third World debt crisis of the 1970s and 1980s? More than a few developing-nation officials listening to Pence likely recalled it all too well.

Xi seems to have anticipated the U.S. broadside. Before Pence spoke he said Belt and Road wasnot for geopolitical purposes. “It is not the so-called trap, as some people say. It is the sunshine avenue where China shares opportunities with the world to seek common development.”

The White House’s strategy here looks like the Dealmaker at work once again: Give the other side a thorough working over, then proceed to the mahogany table and negotiate an agreement to maximum advantage.

Those were the features of the Trump administration’s “maximum pressure” campaigns against North Korea and (as we speak) Iran. Trump’s “deal of the century” in the Mideast, still in development, is another example.

Two Key Flaws

Trump’s brand of diplomacy is flawed in two key ways.

No. 1: It’s foolish to apply what works in the Manhattan real estate market to global strategy. There is little-to-no chance that Trump’s style will deliver the intended results in Iran, North Korea or in the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. Trump may win further concessions on trade when he meets Xi in Argentina later this week, but this will have nothing to do with Pence’s disgracefully bellicose speeches at the two back-to-back gatherings of Asia–Pacific nations.

No. 2: Obsessed with its decades of primacy in the Pacific, the U.S. simply cannot accept China’s inevitable emergence as a regional and global power. This second problem is the larger and more worrisome, driving one mistake after another in Washington’s trans–Pacific strategies. So long as members of U.S. policy cliques see everything Beijing does as a threat, they will fail to grasp the many opportunities for cooperation that a stronger and more prosperous China makes possible. This is more than merely a shame: it is causing a self-inflicted decline.

Washington would do well to learn that it’s futile to try to isolate mainland China from the rest of Asia. It’s like trying to isolate most of a hemisphere from the rest of the planet. And no Asian nation—not even the ever-loyal Japanese—shows any interest in choosing a side in a confrontation that is more or less of Washington’s making.

No undertaking of the magnitude of Belt and Road—which now involves more than 70 nations—will be without its problems, especially at the front end. But Xi’s description of it seems closer than Pence’s. Of the roughly 1,700 projects now in progress, only one—a port that Chinese firms constructed in Sri Lanka—has run into major financing problems, and these appear to reflect Sri Lanka’s misjudgments more than China’s.

To be fair to Pence and his boss, the Trump administration is not the first to confront Asians with an us-or-them choice between the U.S. and China. That error goes to the administration of Barack Obama when it was negotiating the Trans–Pacific Partnership. By pointedly not inviting China to join the TPP, it treated the deal, primarily, as a device to isolate China.

The U.S. has not had a coherent approach to China at least since the first Bush presidency back in the early 1990s, when there was at least some acceptance of China as a rising power.

Beijing eagerly wants to avoid an all-out trade war with the U.S. And this is what will count in Buenos Aires, not Pence’s chest-out posturing. Absent an agreement, the 10 percent tariffs now in place will go to 25 percent in January, and the United States will impose new tariffs on an additional $267 billion worth of Chinese exports. These numbers are what will motivate Xi.

The Chinese recently sent the White House a list 140 concessions they are willing to make, which Trump called insufficient. “Some things were left off,” Trump said breezily after reviewing it. “We will probably get them, too.”

If the Dealmaker really wants a deal, he would have to negotiate with an important trading partner, not an adversary, and drop all suggestions that U.S. primacy in the Pacific remains intact. China has already retaliated with tariffs on $60 billion worth of U.S. products. There is plenty more where that came from if Trump misreads Xi as badly as his vice-president has done.