PATRICK LAWRENCE: The US-China Decoupling

The long, dense economic relationship appears to have passed its peak, writes Patrick Lawrence.

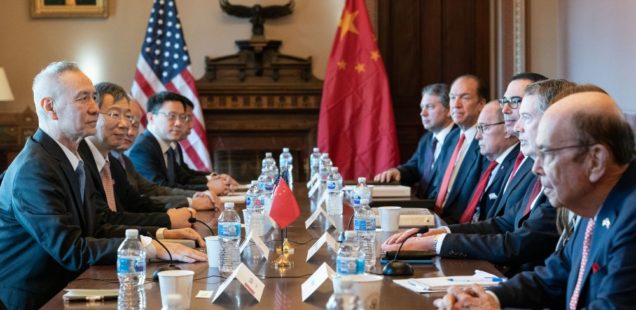

President Donald Trump’s trade war with China is swiftly taking a decisive turn for the worse.

Step by step, each measure prompting retaliation, a spat so far limited to tariff increases, now threatens to transform the bilateral relationship into one of managed hostility extending well beyond economic issues. Should Washington and Beijing define each other as adversaries, as they now appear poised to do, the consequences in terms of global stability and the balance of power in the Pacific are nearly incalculable.

The trade dispute continues to sharpen. Later this week Beijing is scheduled to raise tariffs already in place on $60 billion worth of American exports — the latest in a running series of escalations Washington set in motion nearly a year ago. Two weeks later the U.S., having increased tariffs on $200 billion worth of Chinese products earlier this month, is to consider imposing levies on an additional $325 billion worth of imports from the mainland.

The fallout from these mutually imposed taxes on trade will be considerable all by itself. Global supply chains will inevitably be disrupted — a potential threat to worldwide economic stability. U.S. importers are expected to start shifting purchases away from China in favor of alternative suppliers with lower cost structures. American investors are likely to reconsider the mainland as a production platform, in many cases diverting investment dollars elsewhere.

For its part, China is already rotating its gaze westward toward the Middle East and Europe. As if to underscore the point, the East Hope Group, a large Chinese manufacturer, announced late last week that it plans to invest $10 billion in Abu Dhabi’s industrial sector. Beijing is already drawing Western Europe into its trillion-dollar Belt and Road Initiative. In time, Europe could begin to replace the U.S. as a source of the foreign investment capital China needs.

Decoupling

In the financial markets, this process is termed “decoupling.” The long, dense economic relationship between the U.S. and China, the reasoning runs, appears to have passed its peak.

With bilateral trade talks stalled, both sides have begun to indicate — directly or by inference — that they are now prepared to draw blood. Once the long-term damage begins, as appears increasingly likely, it is difficult to see how there will be any turning back from it.

Two weeks ago, the White House issued an executive order barring purchases of telecommunications equipment from any foreign company deemed to pose a threat to U.S. national security. It also requires American companies to obtain licenses before exporting U.S. telecoms technology to such firms. While an administration official described the order as “company and country agnostic,” it is all but explicitly intended to damage the global position of Huawei, the highly competitive Chinese company that is a leader in cellular telephone sales and 5G telecommunications networks.

Huawei has long been in Washington’s sights. Chief among the allegations against it, the company is accused of providing China with a “back door” into its telecoms networks, so allowing Beijing to spy on any entity using Huawei equipment. The U.S. has never provided evidence of this, and both Huawei and Beijing vigorously deny any such arrangement. The only known back door into Huawei systems was created by the National Security Agency, which hacked its servers at some point between 2010 and 2012; this was revealed in the documents Edward Snowden made public in mid–2013. In effect, the U.S. accuses China of doing what it has already done.

“When it comes to policy caprice motivated by paranoia and Deep State lies, the attack on Huawei is in a class all by itself,” David Stockman, the former White House budget director, wrote on his blog earlier this month. “The whole case has been confected by Washington-domiciled economic nationalists who think prosperity stems from the machinations of the state and that state-sponsored ‘national champions’ are essential to winning the race for global economic and technological dominance.”

Contradictory Narrative

There is little question that freezing Huawei out of the U.S. market and depriving it of U.S.–made components will do damage, in all likelihood lasting, to the company. The Eurasia Group terms the administration’s executive order “a grave escalation with China that at a minimum plunges the prospect of continued trade negotiations into doubt.” But as it has on other policy questions, the Trump administration is tripping over its own contradictory narratives at this point.

Last week the president suggested that the Huawei dispute can be negotiated as part of a broader agreement on trade. At the same time, Dan Coats, the director of national intelligence, has been crisscrossing the country to warnU.S. companies, universities, and other institutions of the perils of doing business with China. Coats’s focus is on the high-technology sector.

There are two lessons to draw from this spectacle. Trump’s position on Huawei gives the game away: If the company is truly a national security threat, it makes no sense to offer it as a chip to be bargained in trade talks with Beijing. Equally, Coats’s barnstorming tour is a clear indication that the national security apparatus is actively seeking to cast China as a strategic threat to the U.S. — as the Pentagon declared it to be in a defense review earlier this year.

Beijing has so far shown restraint in its responses, but there are signs it is stiffening its spine. On Friday it issued a draft of its own set of tighter regulations governing potential cyber-security breaches. Xi Jinping had earlier visited a rare-earth processing facility in Jiangxi Province — a move read as the Chinese leader’s subtle suggestion that Beijing may consider blocking exports of minerals that are essential components in a variety of high-tech devices.

Turning off the supply of rare earths is not the “nuclear option” China may consider it, as there are alternative suppliers. At the same time, the mainland accounts for nearly three-quarters of world supplies. When it blocked sales to Japan during a diplomatic dispute in 2010, prices rose precipitously and there was mayhem among manufacturers dependent on Chinese supplies.

Xi made a remark in Jiangxi that is not to be missed. “We are now embarking on a new Long March,” he said, referencing the famous retreat Mao led after Chinese Nationalists defeated the Red Army in 1934. “And we must start all over again.”

With formal talks lapsed for the time being, there is now no shortage of signaling from either Washington or Beijing. But Xi, China’s most assertive leader since the Great Helmsman, appears to understand the moment as larger than mere gestures. U.S.–China relations have entered a decisive phase. America cannot win in a long-term confrontation with China. Unless Washington opens to a more cooperative partnership with Beijing — an unlikely prospect — this could be the moment China begins to displace the U.S. as the preeminent power in the western Pacific.