Patrick Lawrence: The Power of Images

How the mainstream media uses images to define truth.

In “Lying in Politics: Reflections on the Pentagon Papers,” an essay she published in The New York Review of Books in 1971, Hannah Arendt wrote of a phenomenon she called “defactualization.” Facts are fragile, the late political philosopher argued, in that they tell no story in themselves. This leaves them vulnerable to the manipulations of storytellers. “The deliberate falsehood deals with contingent facts,” Arendt wrote, “that is, with matters which carry no inherent truth within themselves, no necessity to be as they are; factual truths are never compellingly true.”

Letting the facts speak for themselves, in other words, is a bad idea in Arendt’s view. I could not agree more heartily. “It is this fragility of facts that makes deception easy up to a point, and so tempting,” Arendt asserted. Defactualization reflects “disregard for reality.”

How disregarding our mainstream press and broadcasters prove as they purport to inform us of the crisis in Ukraine. The coverage on both sides of the Atlantic is a riot of defactualization at this point, and it appears to worsen the more obvious it is that the Kiev regime is losing a conflict we so recently read it was winning.

Let us consider two cases in which the cynical misuse of fragile facts in the service of predetermined conclusions is usefully obvious. Deception, indeed, has its limits.

In its Tuesday editions The New York Times ran a long takeout headlined, “What Hundreds of Photos Reveal About Russia’s Brutal War Strategy.” This piece adds “shockingly barbaric” to the lengthy list of descriptives Western media commonly deploy—“ruthless,” “indiscriminate,” “primitive,” “criminal,” and so on— as they report the Russian military’s advances. The Times tells us it looked at more than a thousand photographs taken by Times and wire-service photographers, “as well as visual evidence presented by Ukrainian government and military agencies,” to conclude that Russian forces are using “weapons that kill, maim, and destroy indiscriminately—a potential violation of international law.”

Now that the once-but-no-longer newspaper of record has “the narrative” in place, let’s have a look at what is supposed to support the damning conclusions we must find therein. This is where it gets interesting. Arendt would be fascinated—among other things.

We have graphic models of various weapons that look as if they came out of a toy catalog. Here is a D–30 howitzer with a little man beside it, his arm raised as if he is about to order “Fire!” Here is a BM–21 multi-barrel rocket system. The former is described as “a Soviet design used since World War II.” The BM–21 is a “Soviet launch system used since the 1960s.” The implication is that those primitive Russians are deploying weapons a half-century and more old. The models suggest these are pretty thorough upgrades since the 1940s and 1960s, but The Times doesn’t address this point.

Then we have a diagram showing how far shrapnel travels when fragmentation bombs are detonated: 336 feet for 9N210 submunitions, 461 feet for the OF–56 projectile. Then we have a map with red dots in clusters to indicate where various rockets, missiles and other weapons were presumably found and photographed.

Then the pièce de résistance: a dozen of the photographs. These show rockets, missiles, and artillery shells in various places where they landed—in fields, in towns, with barns and houses in the background.

And that’s it. From this we are to accept the narrative presented in the text. Utter bollocks, as the English say. Hocus-pocus start to finish. This is exactly what Hannah Arendt warned of when she wrote of the fragility of facts.

You have a thousand photographs, 12 of which you see. Somewhere in Ukraine a thousand artillery pieces or rocket launchers fired these into a thousand target areas. These are facts as The Times relates them. If we take The Times’s word for it (and I do not generally advise this), at least a thousand artillery shells, rockets, or missiles of one or another kind have landed somewhere on Ukrainian soil since the Russian operation began in late February.

If you have not already twigged to this chicanery, the above-noted are all The New York Times has on offer as facts. The rest is sheer conjuring. Assuming the measurements of dispersed fragmentation are accurate, they are examples of “contingent facts,” true the world over and revealing nothing in themselves about Ukraine, Russia, or any related topic. Those models—the howitzer and the rocket launcher—are nothing more than fun for the whole family: They add nothing.

There is the map with the red dots. Almost all of them appear on the front lines of the conflict—and on either side of these lines. We are assured thus that most artillery is fired and most rockets launched where battles are waged. Who would’ve guessed?

The map, in turn, brings us back to the text. Buried within it, as is The Times’s wont in these cases, we read that some of the shells and rockets in the photographs may have been fired by Ukrainian forces.

I count three conclusions to draw from this unexpected information. One, The Times has no certain idea what the photographs depict; they could show Russian ordnance, or it could be Ukrainian. Two, it follows that the Ukrainians are also using what The Times calls primitive weapons that “kill, maim and destroy.” Three, we are reminded here that all weapons kill, maim and destroy, many of them indiscriminately, and in using these terms The Times is merely inflating its language to maintain our hatred of those Rrrrussians at a desirably high level.

As to the “visual evidence presented by Ukrainian government and military agencies,” I leave readers to draw their own conclusions except to say, shame on The Times for passing off such evidence as if it were from a disinterested source.

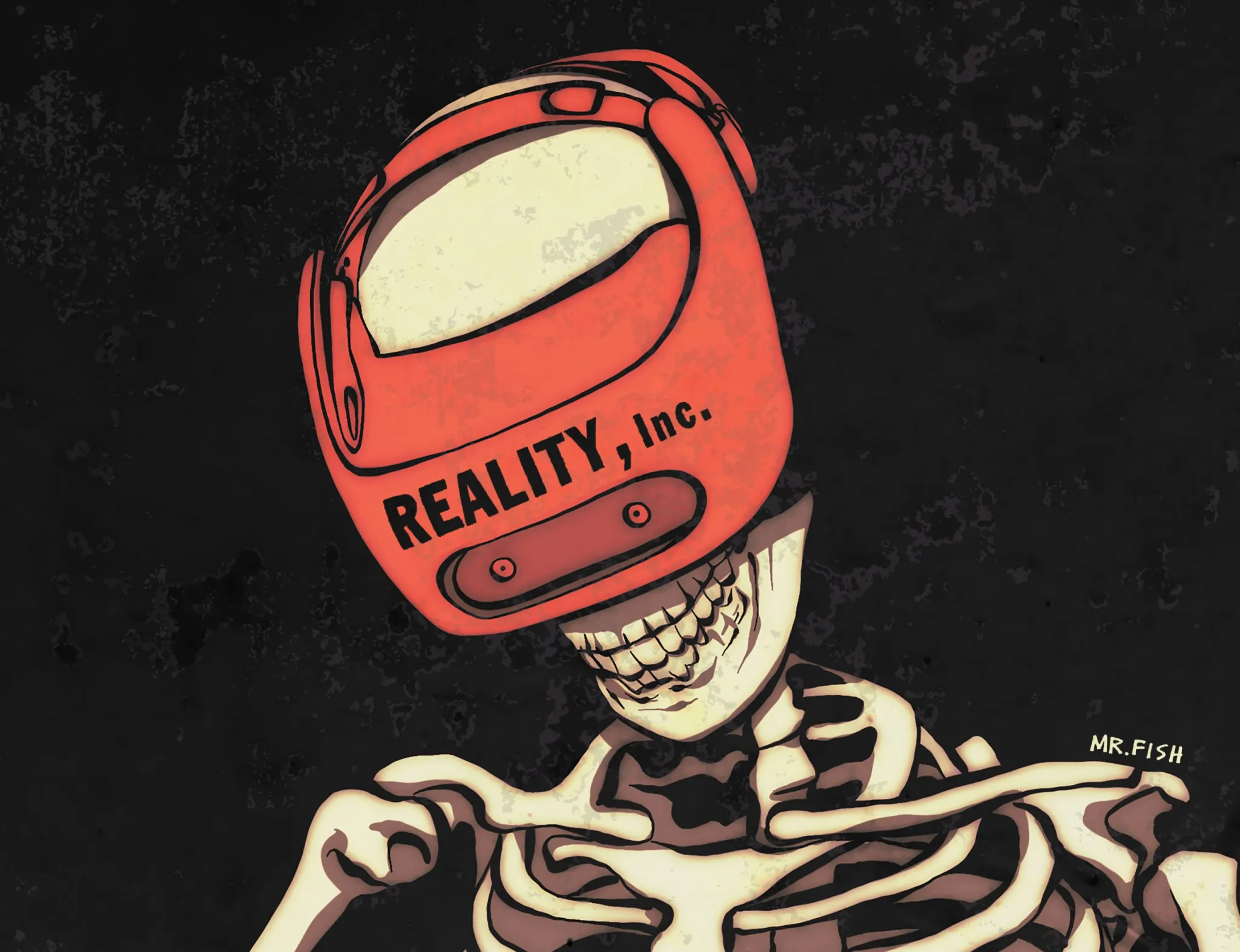

There is one feature of The Times’s report that we must not miss. It is prevalent among those trading in defactualization. This is the report’s dependence on images to make its point. Humankind has understood the power of images since the Lascaux cave painters. They have long been essential to propaganda campaigns. Mussolini was not the first to use images in this way, but Fascist Italy gives us a clear example of their effectiveness.

Photographs are sometimes worth a thousand words, but not always. They just as often require a thousand words. The New York Times has not given us these words. Ten thousand would not be sufficient to make this shabby report stand up to scrutiny.

Reality Check

Have you noticed the new fashion among the mainstream dailies and broadcasters? They lately take to striking poses as deep-dive investigators, marshaling purported evidence as if they have the reach of intelligence agencies. Then they present it, as the spooks do, with the implicit claim, We are telling you this and that is proof enough it is true.

The Times’s silly report on weaponry deployed in Ukraine is a case in point. The BBC gave us another on Monday.

You know there is trouble on the way when the Beeb gives a byline to “Reality Check Team.” What follows is sure to be a fun combination of preposterous and delightful. “There’s mounting evidence” is another sign of the abracadabra to come. The simple translation here is, We cannot prove anything we are about to tell you but we are going to present this as if it is proven.

Here we go again. “Tracking where Russia is taking Ukraine’s stolen grain” is another soufflé of innuendo, images and manipulated facts with no intrinsic meaning that collapses as soon as it is out of the oven.

“There’s mounting evidence that Russian forces in occupied areas of Ukraine have been systematically stealing grain and other produce from local farmers,” Britain’s government broadcaster announces in its bold-face precede. “The BBC has talked to farmers and analyzed satellite images and shipping data to track where the grain is going.”

Problems, instantly.

Before we go any further, where did the Beeb get the purported satellite images? The BBC appears these past years to be so thick with M.I.6 it would be irresponsible not to pose the question. It turns out the images are from Maxar Technologies, which has one foot in Silicon Valley and the other in suburban Washington, where Radiant Solutions, its subsidiary, contracts with the Pentagon to develop military technologies. So, a provenance question straight off the top.

I am not aware, equally, that BBC correspondents have been reporting in Ukrainian territory occupied by Russian forces, but so it seems to be—as in seems.

The sole source of the BBC’s stolen-grain report among Ukrainian farmers is one Dmytro, whose name is not Dmytro and whose grain fields are “a few dozen miles from the frontline.” Since Dmytro’s pastures are occupied by Russian grain thieves, this implies the BBC’s correspondents were 30 or 40 miles inside Russian-controlled territory. I may as well come out and say it: I doubt this is so. There is not one phrase or passage, no descriptive reporting, to tell us what the bylined correspondents actually saw or heard or how they moved around while in Russian-occupied territory.

Another problem: Where was Dmytro whose name is not Dmytro interviewed? The Beeb neglects to tell us. An ordinary viewer of this report or a reader of its text, such as myself, should not have to entertain such doubts.

“They stole our grain. They destroyed our premises, destroyed our equipment.” These are the only two sentences the Beeb quotes from its encounter with Dmytro. When you are in the game as long as I was, you recognize a quotation that is standing on stilts, as this one is. To be blunt once again: These two sentences are almost certainly not authentically from anyone named Dmytro.

Further into the funhouse, as the best is yet to come.

First, there is CCTV footage from cameras Dmytro seems to have installed around his property. Featured here is an image showing “the moment Russian soldiers arrive at a storage facility.” Look at this image and tell me you are able to discern who the soldiers are and where they are arriving. Impossible. There is a “Z” painted on one of the armored personnel carriers, but we have various reports from Russian correspondents on the ground in Ukraine that the Ukrainian army likes to paint these on its own APCs when it wants to pretend it has captured Russian equipment.

And another caveat from the Beeb: “We have blurred some of the surroundings to protect the identities of the farm owners.” I thought there was only one farm and one farm owner, but never mind: I have the soul of a copy editor. Indistinct surroundings that could be anywhere and more than one farmer it will be.

The guts of the BBC report, once we have accepted Dmytro’s assertion that Russians arrived, stole his grain, and drove away, rests on GPS tracking gear he installed in a couple of his trucks—trucks the Russians stole along with the grain. By way of these devices, these trucks were followed as they drove to Crimea and stopped next to a storage facility, which is next to a rail line, “which can be used to transport grain either into Russia or down to ports in southern Crimea.”

I like the “can be used,” as in, We’re not saying it is or has been in this case. And I like the “Z” symbol, the mark of Russian forces in Ukraine, that the Beeb tells us is painted atop a grain silo. It is what silo operators do. They paint military insignia atop their facilities. But you already knew that.

There are maps showing the routes taken, so no worry on this score. And it is very, very clear from these maps: Ukraine is next to Crimea, there are roads connecting them, and Crimea has frontage on the Black Sea. And it is via the Black Sea that Russians are exporting Ukrainian grain. One and one and one is three.

Now the truly nifty part. I just love the satellite images.

There are lots of them, one more amusing than the next. One shows the route to a border crossing called Chonar, and you can see truck traffic on it. Here is one showing grain silos. And behind the silos, clear as a bell, is the “main rail line.” Up the way from that you have your “cargo rail station.” On the main rail line, right up to the cargo rail station, are “cargo trains—with wagons of the type used to transport grain and other produce.” And out front of these things, the absolute caker: There is a line of trucks, one behind the other.

All this is clearly marked with labels, so let there be no ambiguity here as to what is going on.

“Where is the grain taken after Crimea?” the Beeb asks in a subhead. It turns out to go first to Russia, so it can be re-exported with Russian certificates, or it goes straight into the Black Sea for shipment overseas. The BBC has tracked ships, using Lloyds of London data, across the Black Sea to Turkish ports or through the Bosporus to ports in Syria.

More caveats. “It is very hard to track individual shipments of stolen grain,” the BBC acknowledges some way into its report, “but there is plenty of evidence that much of it goes first to Crimea.” Same translation as above: We are not saying any of this is actually so.

The truck traffic along the route from Ukraine to Crimea might be routine, the Beeb finally gets around to telling us. The vehicles in the satellite images, like those rail cars located who knows where, “could be used to transport grain and other produce.”

At the front end of all this, the story has changed. The Russians are no longer stealing grain: They are forcing farmers to sell at below-market prices. At the far end, the Syrians, when queried, have had nothing to say about grain shipments. But the Turks have: They have found no evidence of stolen grain after their own investigation.

You cannot beat this for bunkum, can you?

Once again, it is down to the propagation of images. How dangerously they are wielded among our irresponsible media.

To net this out: I do not know, and neither does any reader of this column, what weapons the Russians deploy in Ukraine and what becomes of Ukraine’s spring and summer grain crops. We are left, many of us, with what William James, the philosopher-turned-psychologist, identified as “the need to believe” he found among Americans.

And now we understand Arendt’s point as to deception’s utility up to a point, and the italics are hers.

“There always comes a point beyond which lying becomes counterproductive,” Arendt wrote in that remarkable essay from which I have quoted. “This point is reached when the audience to which the lies are addressed is forced to disregard altogether the distinguishing line between truth and falsehood in order to be able to survive. Truth or falsehood—it does not matter which any more… truth that can be relied on disappears from public life and with it the chief stabilizing factor in the ever-changing affairs of men.”