PATRICK LAWRENCE: Regrouping the Nuclear Dealmakers

There are three good reasons for Iran to go back to the table, says Patrick Lawrence.

Does the Trump administration want to negotiate peaceably with Iran, or is it intent on bringing the Islamic Republic to its knees while setting the stage for a military confrontation? After a week of intensifying diplomacy — and with more to come in days ahead — the White House will soon have to show its hand. One way or another, Washington’s schizophrenic conduct toward Iran in recent months is about to become more legible.

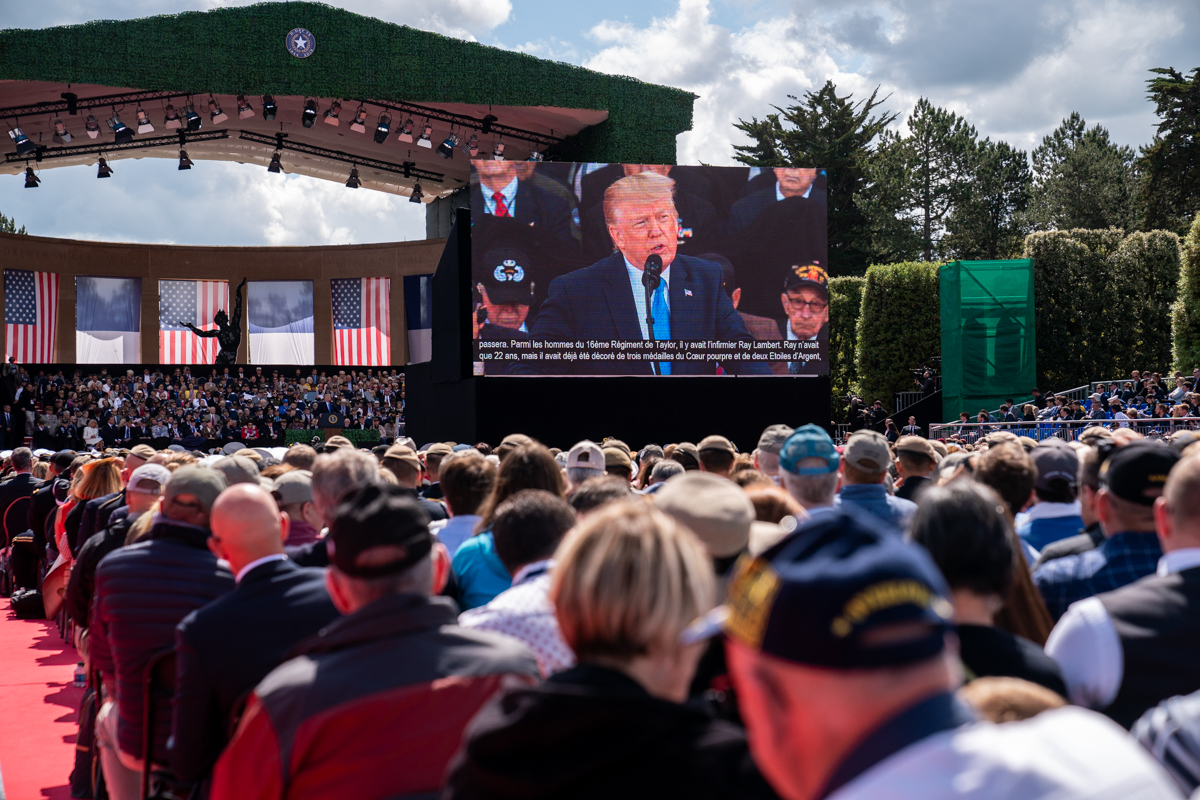

At the moment, what starts to resemble a kind of strategic confusion is all the administration seems to have on offer. During a one-day visit to France last week, President Donald Trump once more reiterated that he was open to negotiations with Tehran. “I understand they want to talk,” he said at a press conference near the D–Day landing beaches in Normandy Thursday. “And if they want to talk, that’s fine. We’ll talk.”

The following day the Treasury Department announced new sanctions on the Persian Gulf Petrochemical Industries Co., Iran’s largest producer of petroleum byproducts. PGPIC accounts for 40 percent of the nation’s petrochemical output and 60 percent of its exports. Treasury alleges that its profits support Iran’s Revolutionary Guard Corps, which the U.S. designated a terrorist organization last April.

Contradictions between what the Trump administration says and does have been evident since John Bolton, the president’s national security adviser, and Secretary of State Mike Pompeo began to fashion a newly confrontational Iran policy earlier this spring. But Washington appears to have taken a step too far when Bolton announced last month that the Pentagon would send a carrier group, bombers, and a missile system to the Persian Gulf, while Pompeo traveled to allied capitals to warn of imminent threats from Iran he never substantiated and few believed were authentic.

Allied Powers Intervening

Alarmed by the swift escalation of tensions between Washington and Tehran, allied powers are now actively intervening in behalf of negotiations to settle a crisis the U.S. has singlehandedly precipitated. Russia has also stepped up its diplomatic efforts. In effect, these nations are challenging Washington to declare its objective: Is it diplomacy, or another dangerous “regime change” operation with the threat of military conflict?

Emmanuel Macron made this clear during Trump’s visit to the Normandy beaches last week. While supporting Trump’s stated intent to reopen the nuclear accord he abandoned last year, the French president also listed “a regional situation as peaceful and secure as possible” among the goals he purports to share with Trump. Macron’s challenge to the Bolton–Pompeo axis could hardly be plainer.

While Trump and Macron marked D–Day’s 75thanniversary, Tokyo announced that Prime Minister Shinzo Abe is to travel to Tehran this week for talks with President Hassan Rouhani and Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei. There is an even-or-better chance this will prove crucial to growing international efforts to defuse the Iran crisis.

The Japanese premier secured Trump’s approval for his diplomatic demarche when he offered to mediate between the U.S. and Iran during Trump’s four-day state visit to Japan late last month. Jiji, a Japanese wire service, reported Sunday that Abe intends to propose a Trump–Rouhani summit while in Tehran. If he does, the Japanese leader will effectively confront Trump head on: What will it be, Mr. President, war or peace?

Last Tuesday the Tehran Times reported that Sergei Rybakov, Russia’s deputy foreign minister, proposed new talks — a joint commission, as he called it — convened by the signatories of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, or JCPOA, as the 2015 pact governing Iran’s nuclear programs is known. These are seven: the “P5+1” group — the U.S., Britain, France, Russia, China and Germany — plus Iran. While France and the other European signatories were prepared to renegotiate the accord as soon as the U.S. withdrew from it last year, Russia and China initially supported Iran’s resolute refusal to refashion a hard-won agreement whose terms it has rigorously observed.

Questions arise. Should Iran now capitulate? Should it assent to new talks on the nuclear deal and related issues in response to Washington’s abrogation of the accord? Reversing his earlier position, Mohammad Javad Zarif, Iran’s gifted foreign minister, now signals that Tehran is open to renewed negotiations provided they are based on parity and mutual respect — conditions that, it must be said, may prove beyond the Trump administration’s capacities to meet.

There are three reasons Zarif is right to alter course.

US Actions Require a Response

First, the layers of sanctions the Trump administration continues to impose — and now its threatening displays of military power in the Persian Gulf — are highly volatile “facts on the ground” that take the Iran crisis well beyond the nuclear accord alone. These require a response, as the French, the Japanese and the Russians now acknowledge. “Convening a joint commission would be a right step to take,” Rybakov explained last week, “because we need to look into all aspects of the current, I would say, crisis situation around the JCPOA.”

Airing of Tehran’s Perspective

Second, new talks would allow Tehran to air its perspectives on the questions the U.S., with the acquiescence of its European allies, wants in a rewritten accord. Chief among these are Iran’s ballistic missile program and its support for the Assad government in Syria and for militias active in Iraq. The U.S. has relentlessly distorted Iran’s positions on these issues. Assuming renewed negotiations would be multi-sided, this could now be corrected in an international context.

Washington’s complaints about Iran’s missile tests do not stand up to scrutiny on any number of grounds. Iran is not developing missiles designed to carry nuclear warheads, as Washington contends, and in any case the U.S. argument is circular: Iran has no fissile material to make warheads by virtue of the JCPOA. It is active in Syria and Iraq at the invitation of both governments and to combat Sunni extremism — the very terrorism the U.S. accuses it of backing.

Not to be missed in this latter connection, Zarif has long called for a regional security mechanism through which diplomatic solutions to conflicts of all varieties can be negotiated. In its latest iteration, announced two weeks ago, he proposed a non-aggression pact to be signed by Iran “and its neighbors in the Gulf,” as Zarif put it. Is this the thought of a “terrorist” state intent on destabilizing the region?

Sergei Lavrov, Russia’s foreign minister, said four days after Zarif’s announcement that Moscow was prepared to facilitate such an accord. As Rybakov put it, making a delicately veiled reference to the U.S. and its Sunni-nationalist allies, “You have a positive political alternative to a very destructive course that unfortunately prevails in some places.”

Effective Multi-Sided Format

Finally, new talks convening the JPCOA’s signatories would amount to a variant of the six-party talks on North Korea that began in 2003. While those talks were discontinued early in the Obama administration, the multi-sided format proved an effective mechanism in the intervening years. The advantage is that all issues can be negotiated among the nations with a direct interest in them. In this case, this would include Iran, the P5+1 group, and possibly Japan, given its close relations with Tehran and Premier Abe’s surprising diplomatic initiative this week.