Let us consider the grist of the talks the U.S. president hosted at the presidential retreat in Maryland last week. This will not take long.

My goodness. President Joe Biden and the press serving his regime pumped so much hot air into that three-sided Asian summit at Camp David last week it is a wonder the entire occasion didn’t float away like an overfilled balloon.

Here’s the thing: It will.

Biden brought together the South Korean president and the Japanese premier to forge some kind of new security pact that is intended to endure, as Biden bloviated, “not just this year, not just next year, forever.” You have to love it: Rarely do we get clownish hyperbole of such high quality. But we must remind ourselves from whom this silliness issues. Then we can make some minimal sense of nonsense, if you will suffer a paradox.

Let us consider the grist of the talks Biden hosted at the presidential retreat in Maryland. This will not take long.

President Yoon Suk Yeol and Premier Fumio Kishida are two rightist conservatives with very low approval ratings back in South Korea and Japan respectively. They each flew to Washington for White House summits earlier this year, reflecting the Biden regime’s plan to fortify an arc of security alliances running from Seoul through Tokyo, Manila and Singapore all the way to Canberra.

The prima facie objective of this strategy, as obvious as the sun’s rise in the morning, is to surround China so as to contain its influence in the Pacific and, you have to figure, at some point to confront it militarily. I find it weird beyond weird that Biden continues to insist that his regime is not “anti–China” and still expects anyone to take him seriously.

The Camp David summit last Friday was supposed to be a big moment in this extravagant project. The three leaders agreed to expand military exercises they already conduct, to establish a three-way communications hotline, to gather yearly for a trilateral summit and to extend cooperation on ballistic missile deployments, which is Orwell-speak for putting more U.S. missiles on South Korean and Japanese soil.

‘Camp David Principles’

The White House calls these agreements “the Camp David Principles.” At this point I need help, and maybe you do, too. Military drills; red telephones in Seoul, Tokyo and Washington; talking together once a year, more American hardware at the western end of the Pacific: I cannot find a single principle in any of what the three presented to the world when they were finished last Friday afternoon.

And there is a good reason for this. Washington has been pushing its more pliant Asian allies for years to sign on to its new Cold War in the Pacific. But push has not yet come to shove. Were Washington to shove Seoul and Tokyo — to tell them the hour has come to engage the People’s Republic in war — it would be instantly clear that East Asians share few of America’s “principles” and want no part of an open conflict with their largest neighbor, largest trading partner and civilizational brothers and sisters.

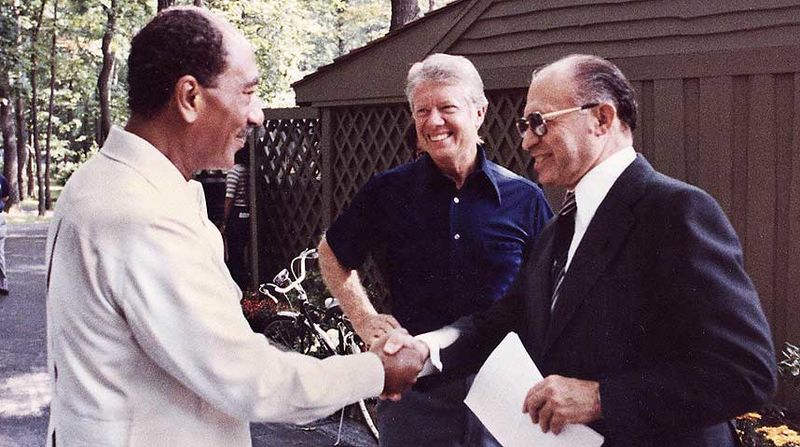

The mountain Biden wants to make out of this molehill surpasses all belief, in my read. The Camp David setting and the “Camp David Principles” are clunky props in our addled president’s effort to summon the Camp David Accords former President Jimmy Carter negotiated with Egypt’s Anwar El-Sadat Sadat and Israel’s Menachem Begin back in 1978. There is only one thing more supercilious: The New York Times’ fawning coverage of the summit as brought to you by Peter Baker, the paper’s White House correspondent.

A clown covering a clown will always make entertaining reading, I always say.

It is that time in a presidential term, we have to conclude, when the commander-in-chief thinks about his place in the history books. All sorts of oddities appear at this stage in the four-year cycle that rules the White House. Biden has a good chance of making the history books, all right, but — it’s another conversation — not as the statesman, the diplomat, the banner-bearing global leader he wishes he were but never will be.

Sadat, Carter and Begin at Camp David in September 1978. (Wikimedia Commons)

To be clear, some things worth thinking about occurred at Camp David last week. Looking past our president’s poses, what were these?

To begin, it does not appear that Biden is at all cognizant of the social and political dynamics of South Korea and Japan. To be fair, I cannot recall any president who took an interest in East Asians and their societies apart from their use as spear-carriers in the service of the imperium. Either this kind of thing never makes the briefing books or presidents don’t read the briefing books. The latter is certainly true in Biden’s case, which isn’t to say the former is not also the case.

Kishida, elected in October 2021, and Yoon, elected six months later, effectively presented Biden with a moment on which he and his national security people think they can capitalize. They are both rightist hawks and hard-liners on China and North Korea. Both represent long-established constituencies in Northeast Asian politics whose sensibilities were shaped during the first Cold War and whose leaders are, paradoxically, avowed nationalists but given to a pitiful obedience to the U.S. imperium.

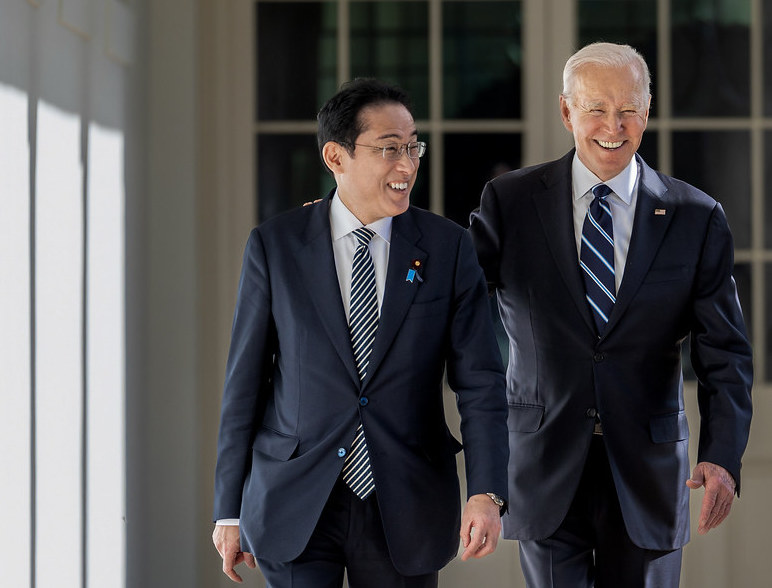

Kishida and Biden at the White House in January. (White House, Cameron Smith)

But there are various limits to their hawkery and — a judgment call, this — even to their loyalty to the U.S. As noted, it is hard to see either Yoon or Kishida leading his nation into war with the mainland short of circumstances so extreme we need not bother about them.

Neither Yoon nor Kishida represents any kind of national consensus. Let’s not miss this salient reality.

In the Japanese case, Kishida and the rest of the governing Liberal Democratic Party face well-known constitutional constraints and a current of pacifism that remains strong even if Western media rarely write about it. Kishida, not to be missed, was not on for Biden’s typically insensitive idea of bringing Japan into “strategic planning” — how these phrases mask the Strangeloves of our time — for use of nuclear weapons against either North Korea or China.

Politics are even more interesting in the nation that gave the world Kim Dae-jung and Kim Young-sam after 38 years of U.S.–backed dictators ended in the 1990s. South Koreans enjoy an admirably charged political culture. There remains a pronounced anti–Communist streak, yes, but it has a certain dated fustiness about it, I have long thought. KDJ’s “Sunshine” policy toward the North and an economically fruitful, diplomatically collaborative relationship with China were both alive and well during the presidency of Moon Jae-in, Yoon’s predecessor.

Yoon greeting Biden and First Lady Jill Biden in Washington in April. (White House/Adam Schultz)

So much for Biden’s forever-and-a-day grandiosity last week, in other words. The thought seems to have been that Sinophobic paranoia has at last spread to the other end of the Pacific and will trump in some enduring way all other political currents in these societies. Dumb and dumber.

Only people far away who concoct policies without leaving their Washington offices could entertain such fantasies. You have to conclude that these people are Orientalists at heart, to whom Asians are still merely stick figures with no shred of human complexity to them.

Biden and his policy planners seem to have surmised that two East Asian China hawks had come up at the same time like matching fruit on a slot machine. This does not work, either, as Japan’s hawkish factions do not match South Korea’s.

The problem here goes back much further than the animosities related to Japan’s use of “comfort women” during World War II, history texts Koreans consider objectionable and disputed islands. When Japan began to modernize, in the late 1860s, it sought to enhance its identification with Europeans by looking down on Chinese and Koreans as dark savages with whom the Japanese had nothing in common. The thought that the Japanese are “the white men of Asia,” as the phrase was, may seem preposterous — and is, indeed — but the underlying condescension lingers, unfortunately.

‘You Can Never Become a Westerner’

China’s Wang Yi in 2019. (Palácio do Planalto, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

Wang Yi, China’s always interesting foreign minister, addressed this question in a video pointedly disseminated shortly before the Camp David summit. Wang seems to have puzzled most Western correspondents, but never mind them: He was talking straight to the Japanese. “No matter how blond you dye your hair or how sharp you shape your nose,” he said, “you can never become a European or an American, you can never become a Westerner.”

As if his point were not clear enough, Wang added, “We must know where our roots are.” It is possible to make too much of Asians’ historical and ethnic roots, the shared Confucian tradition, the common identity as non–Western and so on. But it is also possible to make too little of it. And it is impossible to make too much of geographic realities: The Japanese and Koreans live next door to China, not 5,000 miles distant.

“I want to thank you both for your political courage that brought you here,” Biden said as he welcomed Yoon and Kishida at Camp David’s gate. I don’t read the occasion this way. It is not so big a deal for South Korean and Japanese leaders to meet: Kim Dae-jung traveled to Tokyo in 2000 to declare famously it was time for the two nations to look forward, not back. That took courage in the context of the time.

I reckon Yoon and Kishida were more in the way of cowardly in not facing the 21st century’s complexities, multipolarity high among them. They instead reverted to an old, demeaning dependence on the American imperium — signaling this in their obsequious acquiescence to Biden’s sweeping declarations of an historically significant turn in trans–Pacific relationship. Say “Yes,” be courteous, and do as little as possible: This is an established tactic when East Asians must mollify the crude heathens in Washington.

China was supposed to be inflamed by the Camp David events, and I suspect the Biden regime and the American press wanted it to be angered so as to lend the occasion magnitude. I was all the more struck by how casually Beijing seemed to shrug it off. My read: Beijing certainly views the U.S. as a grave threat to its security, but it well recognizes the practical limits of its allies’ loyalties.

Let’s put it this way: Try to imagine Seoul or Tokyo committing troops, ships, and planes to a cross–Strait war in defense of Taiwan led by the U.S. military. I am sure readers can finish this paragraph very well on their own.

Global Times, the Beijing tabloid that reflects official opinion, asserted that Biden was building “a mini–NATO” with the Koreans and Japanese. I am sure something like this is the intent, but I share with the Chinese the thought that any such project will be a long time getting off the ground, if indeed it ever does — and let us not count the Biden regimes’ hot air balloons.

PATRICK LAWRENCE: Biden’s Pointless Asian Summit

Let us consider the grist of the talks the U.S. president hosted at the presidential retreat in Maryland last week. This will not take long.

My goodness. President Joe Biden and the press serving his regime pumped so much hot air into that three-sided Asian summit at Camp David last week it is a wonder the entire occasion didn’t float away like an overfilled balloon.

Here’s the thing: It will.

Biden brought together the South Korean president and the Japanese premier to forge some kind of new security pact that is intended to endure, as Biden bloviated, “not just this year, not just next year, forever.” You have to love it: Rarely do we get clownish hyperbole of such high quality. But we must remind ourselves from whom this silliness issues. Then we can make some minimal sense of nonsense, if you will suffer a paradox.

Let us consider the grist of the talks Biden hosted at the presidential retreat in Maryland. This will not take long.

President Yoon Suk Yeol and Premier Fumio Kishida are two rightist conservatives with very low approval ratings back in South Korea and Japan respectively. They each flew to Washington for White House summits earlier this year, reflecting the Biden regime’s plan to fortify an arc of security alliances running from Seoul through Tokyo, Manila and Singapore all the way to Canberra.

The prima facie objective of this strategy, as obvious as the sun’s rise in the morning, is to surround China so as to contain its influence in the Pacific and, you have to figure, at some point to confront it militarily. I find it weird beyond weird that Biden continues to insist that his regime is not “anti–China” and still expects anyone to take him seriously.

The Camp David summit last Friday was supposed to be a big moment in this extravagant project. The three leaders agreed to expand military exercises they already conduct, to establish a three-way communications hotline, to gather yearly for a trilateral summit and to extend cooperation on ballistic missile deployments, which is Orwell-speak for putting more U.S. missiles on South Korean and Japanese soil.

‘Camp David Principles’

The White House calls these agreements “the Camp David Principles.” At this point I need help, and maybe you do, too. Military drills; red telephones in Seoul, Tokyo and Washington; talking together once a year, more American hardware at the western end of the Pacific: I cannot find a single principle in any of what the three presented to the world when they were finished last Friday afternoon.

And there is a good reason for this. Washington has been pushing its more pliant Asian allies for years to sign on to its new Cold War in the Pacific. But push has not yet come to shove. Were Washington to shove Seoul and Tokyo — to tell them the hour has come to engage the People’s Republic in war — it would be instantly clear that East Asians share few of America’s “principles” and want no part of an open conflict with their largest neighbor, largest trading partner and civilizational brothers and sisters.

The mountain Biden wants to make out of this molehill surpasses all belief, in my read. The Camp David setting and the “Camp David Principles” are clunky props in our addled president’s effort to summon the Camp David Accords former President Jimmy Carter negotiated with Egypt’s Anwar El-Sadat Sadat and Israel’s Menachem Begin back in 1978. There is only one thing more supercilious: The New York Times’ fawning coverage of the summit as brought to you by Peter Baker, the paper’s White House correspondent.

A clown covering a clown will always make entertaining reading, I always say.

It is that time in a presidential term, we have to conclude, when the commander-in-chief thinks about his place in the history books. All sorts of oddities appear at this stage in the four-year cycle that rules the White House. Biden has a good chance of making the history books, all right, but — it’s another conversation — not as the statesman, the diplomat, the banner-bearing global leader he wishes he were but never will be.

Sadat, Carter and Begin at Camp David in September 1978. (Wikimedia Commons)

To be clear, some things worth thinking about occurred at Camp David last week. Looking past our president’s poses, what were these?

To begin, it does not appear that Biden is at all cognizant of the social and political dynamics of South Korea and Japan. To be fair, I cannot recall any president who took an interest in East Asians and their societies apart from their use as spear-carriers in the service of the imperium. Either this kind of thing never makes the briefing books or presidents don’t read the briefing books. The latter is certainly true in Biden’s case, which isn’t to say the former is not also the case.

Kishida, elected in October 2021, and Yoon, elected six months later, effectively presented Biden with a moment on which he and his national security people think they can capitalize. They are both rightist hawks and hard-liners on China and North Korea. Both represent long-established constituencies in Northeast Asian politics whose sensibilities were shaped during the first Cold War and whose leaders are, paradoxically, avowed nationalists but given to a pitiful obedience to the U.S. imperium.

Kishida and Biden at the White House in January. (White House, Cameron Smith)

But there are various limits to their hawkery and — a judgment call, this — even to their loyalty to the U.S. As noted, it is hard to see either Yoon or Kishida leading his nation into war with the mainland short of circumstances so extreme we need not bother about them.

Neither Yoon nor Kishida represents any kind of national consensus. Let’s not miss this salient reality.

In the Japanese case, Kishida and the rest of the governing Liberal Democratic Party face well-known constitutional constraints and a current of pacifism that remains strong even if Western media rarely write about it. Kishida, not to be missed, was not on for Biden’s typically insensitive idea of bringing Japan into “strategic planning” — how these phrases mask the Strangeloves of our time — for use of nuclear weapons against either North Korea or China.

Politics are even more interesting in the nation that gave the world Kim Dae-jung and Kim Young-sam after 38 years of U.S.–backed dictators ended in the 1990s. South Koreans enjoy an admirably charged political culture. There remains a pronounced anti–Communist streak, yes, but it has a certain dated fustiness about it, I have long thought. KDJ’s “Sunshine” policy toward the North and an economically fruitful, diplomatically collaborative relationship with China were both alive and well during the presidency of Moon Jae-in, Yoon’s predecessor.

Yoon greeting Biden and First Lady Jill Biden in Washington in April. (White House/Adam Schultz)

So much for Biden’s forever-and-a-day grandiosity last week, in other words. The thought seems to have been that Sinophobic paranoia has at last spread to the other end of the Pacific and will trump in some enduring way all other political currents in these societies. Dumb and dumber.

Only people far away who concoct policies without leaving their Washington offices could entertain such fantasies. You have to conclude that these people are Orientalists at heart, to whom Asians are still merely stick figures with no shred of human complexity to them.

Biden and his policy planners seem to have surmised that two East Asian China hawks had come up at the same time like matching fruit on a slot machine. This does not work, either, as Japan’s hawkish factions do not match South Korea’s.

The problem here goes back much further than the animosities related to Japan’s use of “comfort women” during World War II, history texts Koreans consider objectionable and disputed islands. When Japan began to modernize, in the late 1860s, it sought to enhance its identification with Europeans by looking down on Chinese and Koreans as dark savages with whom the Japanese had nothing in common. The thought that the Japanese are “the white men of Asia,” as the phrase was, may seem preposterous — and is, indeed — but the underlying condescension lingers, unfortunately.

‘You Can Never Become a Westerner’

China’s Wang Yi in 2019. (Palácio do Planalto, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

Wang Yi, China’s always interesting foreign minister, addressed this question in a video pointedly disseminated shortly before the Camp David summit. Wang seems to have puzzled most Western correspondents, but never mind them: He was talking straight to the Japanese. “No matter how blond you dye your hair or how sharp you shape your nose,” he said, “you can never become a European or an American, you can never become a Westerner.”

As if his point were not clear enough, Wang added, “We must know where our roots are.” It is possible to make too much of Asians’ historical and ethnic roots, the shared Confucian tradition, the common identity as non–Western and so on. But it is also possible to make too little of it. And it is impossible to make too much of geographic realities: The Japanese and Koreans live next door to China, not 5,000 miles distant.

“I want to thank you both for your political courage that brought you here,” Biden said as he welcomed Yoon and Kishida at Camp David’s gate. I don’t read the occasion this way. It is not so big a deal for South Korean and Japanese leaders to meet: Kim Dae-jung traveled to Tokyo in 2000 to declare famously it was time for the two nations to look forward, not back. That took courage in the context of the time.

I reckon Yoon and Kishida were more in the way of cowardly in not facing the 21st century’s complexities, multipolarity high among them. They instead reverted to an old, demeaning dependence on the American imperium — signaling this in their obsequious acquiescence to Biden’s sweeping declarations of an historically significant turn in trans–Pacific relationship. Say “Yes,” be courteous, and do as little as possible: This is an established tactic when East Asians must mollify the crude heathens in Washington.

China was supposed to be inflamed by the Camp David events, and I suspect the Biden regime and the American press wanted it to be angered so as to lend the occasion magnitude. I was all the more struck by how casually Beijing seemed to shrug it off. My read: Beijing certainly views the U.S. as a grave threat to its security, but it well recognizes the practical limits of its allies’ loyalties.

Let’s put it this way: Try to imagine Seoul or Tokyo committing troops, ships, and planes to a cross–Strait war in defense of Taiwan led by the U.S. military. I am sure readers can finish this paragraph very well on their own.

Global Times, the Beijing tabloid that reflects official opinion, asserted that Biden was building “a mini–NATO” with the Koreans and Japanese. I am sure something like this is the intent, but I share with the Chinese the thought that any such project will be a long time getting off the ground, if indeed it ever does — and let us not count the Biden regimes’ hot air balloons.