“In the shade of an olive tree.”

A grandmother remembers al–Nakba.

Note to readers: After ruminating on this matter, and with the encouragement of various people who have written to us, we have decided to make our Palestinian Voices series freely available to everyone: There will be no paywalls throughout this series, and we now republish “In the shade of an olive tree.” Our initial intent was to honor those who supported Cara’s journey to the West Bank by contributing to her fundraising campaign. We now thank these generous supporters by making the work they made possible available to everyone. Anyone who may wish to add his or her support can do so by subscribing to The Floutist.

As earlier noted, we have created an archive, under the same title, where the whole of the Palestinian Voices series is available.

Please try to remember that what they believe, as well as what they do and cause you to endure, does not testify to your inferiority but to their inhumanity and fear.

—James Baldwin, The Fire Next Time, 1963.

Samia, whom I had not yet met, sent a cab to pick me up at my hotel. I met the driver near the terrace of the Notre Dame Center, a Christian site across from the New Gate—one of seven main entrances into Old Jerusalem.

We drove north, through the labyrinthine and densely populated streets of East Jerusalem, where most of the city’s Arabs live. The driver, a friendly man, used our time together to practice his English and to teach me a few words of Arabic. There was no A/C in the old taxi, and the late morning was already becoming unbearably hot.

I texted Samia from the car to let her know I was on my way. I arrived to find a pleasant, middle-class house, single-storied. Her young and pretty assistant opened the door when I rang the bell. She ushered me into the living room, where my hostess was seated in an elegant wingback chair, one foot resting on a padded stool. A cane was propped on the chair next to her.

The room was a cool, inviting oasis. Family pictures hung on walls. A black-and-white photo of a handsome man in his middle age caught my eye: Samia’s husband when he was still alive.

We introduced ourselves. Samia has an intelligent and kind face, a genuine smile, and a beautiful crown of silver hair. I felt immediately at ease. As I took a seat, the young woman carried in a tray and placed it before me on a low coffee table. She set out a pot of tea and several porcelain plates laden with cookies and small cinnamon rolls. This was my introduction to Samia Nasir Khoury and Arab hospitality.

■

I had been in email communication with John Whitbeck as I planned my trip to Palestine. Whitbeck, an international lawyer who resides in Paris, served as a legal advisor to the Palestinian negotiating team in Cairo in April/May 1994 and later at the Camp David summit in 2000. He knows many people throughout the land of Palestine and suggested I might like to meet with Samia, who he identified as a “grandmother.”

Grandmother. How very much and very little is conveyed by that often dismissive and sentimentalized noun.

I had arrived from Europe just a few days earlier. This was my first meeting with a Palestinian Arab, a Christian, and I had no idea what to expect or even what, specifically, to ask. I had come to Palestine to meet and listen to Palestinians, I explained, to hear your stories of life under Israeli occupation. To learn about your hopes and aspirations for Palestine. Those in the West know very little of Palestine or Palestinians, whose humanity has been too effectively erased. I had come to counter this, to see and listen.

One of the sweets on offer was a date-filled delicacy called ma’amoul, popular in the Arab world, although I didn’t know this at the time. I would come across the same treat again, in a very different situation in the old city of Al Khalil, the original Arabic name for Hebron. Another story for another time. All of the cookies on the platter before me had been baked for the Easter holiday, which had recently passed.

We sipped tea and warmed to each other as we conversed. And as Samia’s story unfolded it began to dawn on me—with a sense of shock, but also of my extraordinary and unexpected good fortune—that my 91-year-old companion was a living witness to al–Nakba, the Catastrophe, as Palestinians call the Israelis’ campaign in the late 1940s to drive them from their ancestral land. Soon I was bent over my journal scribbling notes as quickly as I could.

The Nasirs, I learned, are a large and prominent Palestinian family, the women no less accomplished and influential than the men. Nabiha Nasir, Samia’s aunt, founded what would later become the West Bank’s premier institution of higher education, Birzeit University, as a girls school in 1924.

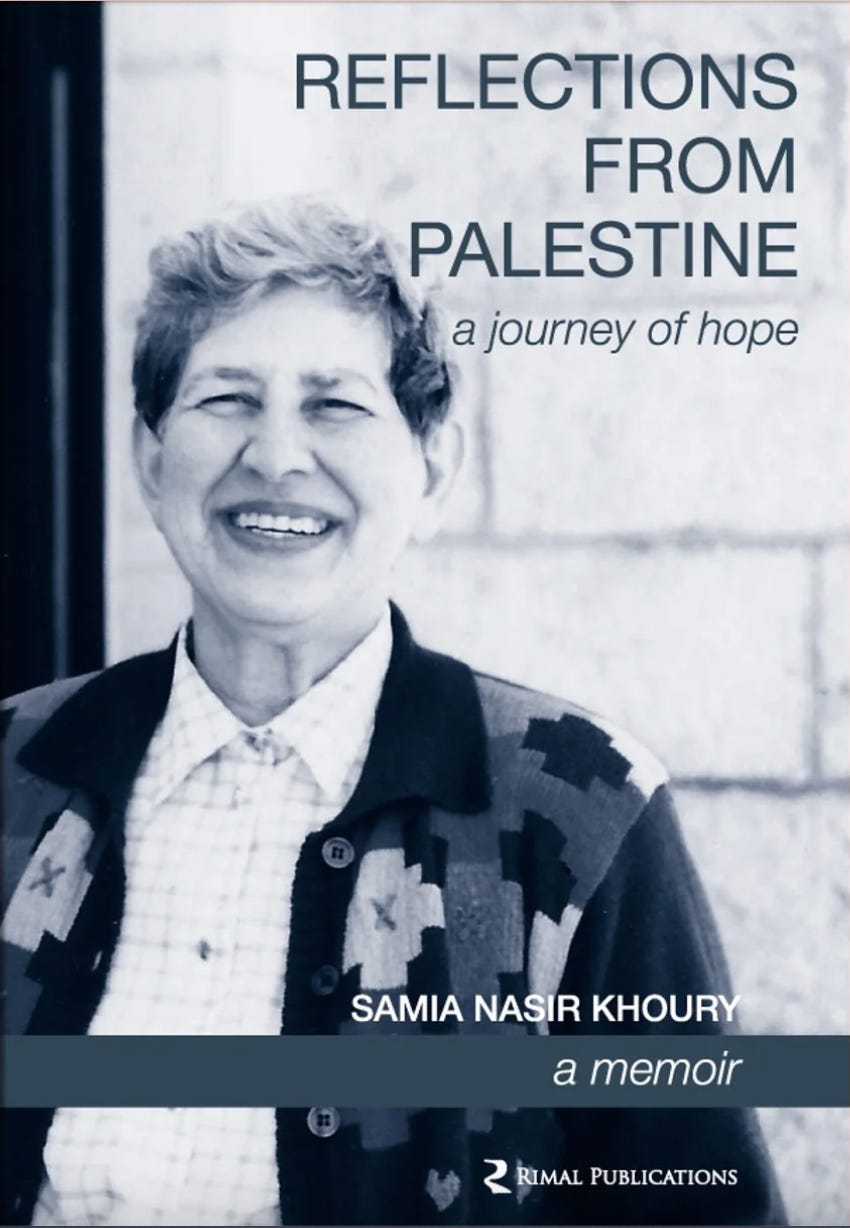

Samia’s sister, Rima Tarazi, who I met in my final days in the West Bank, is a respected Palestinian composer, and their cousin, Sumaya Farhat Nasir, is a peace activist and writer who travels throughout Europe lecturing on the Palestinian struggle for freedom and justice. Kamal Nasir, the much-admired Palestinian poet, assassinated by Israeli special forces in Lebanon in 1973, was yet another cousin. A decade ago, when she was in her 80s, Samia published her memoirs under the title, Reflections from Palestine: A Journey of Hope.

In 1948, when Samia was 15, her family was living in the village of Birzeit, which is just north of Al-Bireh and Ramallah. Samia was enrolled in her aunt’s school; her father, having retired from a long professional career in Jerusalem, taught there.

Samia described what she witnessed this way:

It was summer and hot. July, I think. I was on a terrace reading, sitting in the shade beneath an olive tree, when I looked up and saw a long line of people walking toward the village.

I didn’t know what I was seeing. I ran down the hill to find out what was happening. It was hot, the middle of summer, and these people had been walking for days.

Samia paused, and then explained that those she saw walking toward Birzeit were victims of al–Nakba. They were refugees:

They were from two villages, Lydda and Ramleh, where the Ben-Gurion airport is now. They had been forced out of their homes at gun point. They were stripped of everything, money and jewelry, and forced to walk. Ben-Gurion had been asked, ‘What shall we do with these people?’ He didn’t say anything. He just waved his hand.

My aunt opened the school’s storeroom and fed all of the people. They had been walking for days without food. We cooked for whoever came to us during that time. There were students boarding at the school from all over, from Jaffa and Haifa. They were sent home. One boy was from Galilee. He stayed at the school until the Red Cross took him home.

When she finished this story Samia sat quietly for some time. In the silence I could almost see the long line of people she described. And then, as if echoing my thoughts, and with a deep sadness in her voice, she said, “The scene has never left me.”

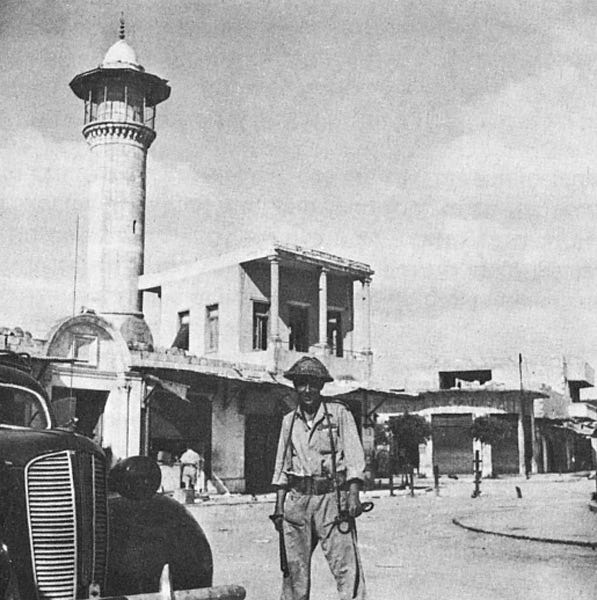

Having researched these events, I know now that Israel’s assault on the two towns Samia mentioned began in the second week of July 1948, two months after Israel declared its sovereignty. Lydda had the unfortunate distinction of being the first Palestinian village subjected to aerial bombardment. When Jewish forces finally entered the city, the few remaining resistance fighters—poorly armed and with little or no training—retreated to the Dahamish Mosque in the village center. There they were quickly overwhelmed and forced to surrender—and they were promptly massacred inside the mosque.

Israeli troops swept through Lydda on a killing rampage. When they were finished, 426 men, women, and children had been slaughtered—176 inside the mosque. Earlier in 1948—by the first week of January, indeed— Ben-Gurion and his colleagues, distinguished European Jews and racist fanatics in charge of overseeing the de-Arabization of Palestinian land, had decided to make no distinction between men, women, or children. This policy remains in effect today, most vividly in Gaza, where the bodies of women and children continue to pile up.

Jewish soldiers quickly emptied the town of Lydda. People were forced out of their homes in the middle of the night, stripped of all possessions but for the clothes they were wearing—women were specifically targeted for their jewelry—and sent walking without food or water toward Ramallah, a distance of some 50 kilometers. The houses were subsequently looted.

The attack on Ramleh started on 12 July. Jewish troops entered the village on 14 July and began emptying the city: They imprisoned thousands of civilians and forced those not arrested to flee westward by foot. Then they looted all that remained—houses, churches, mosques. Nothing was spared. The expulsion orders for the two villages were signed by none other than Yitzhak Rabin, a future prime minister and Nobelist, who also directed the military operation.

This was the brutality from which the people Samia saw from the shade of her olive tree that summer day were fleeing.

The cleansing of Lydda and Ramleh was one of the largest expulsions of Palestinian civilians at one time. From 50,000 to 70,000 people were forced to flee. Many people died from heat exhaustion on the forced march, which is also known as the Lydda Death March. Jews who immigrated to the new state of Israel settled in the homes left behind, a policy intended to ensure that Palestinian would never return.

Lydda and Ramleh were well within the territory designated by international agreement for the Arab state of Palestine. But Ben-Gurion took every opportunity available to him to steal additional land beyond what the U.N. had handed over to the new state of Israel—56 percent of Palestine. By the time the Zionist militias and the new Israeli army concluded al–Nakba, 78 percent of the land of Palestine had been claimed for Israel—all of this in complete violation of U.N. Resolution 181.

■

The contacts I made throughout the West Bank in the course of my journey reminded me, to my bitterness, of how little has changed since the time Samia described as we spoke together. During al–Nakba, Jewish troops sneaked through Palestinian villages in the dark, affixed sticks of dynamite to houses, and blew them up while the occupants were asleep inside, thus causing maximum casualties to all civilians but mainly to women and children.

Many of those I met reported that it is the same today. Just as routinely, the Israeli Occupation Forces conduct their raids in the middle of the night to cause maximum fear and terror. All of this is precisely what we witness in Gaza. And all of my contacts now anticipate that this aggression will increase across the West Bank—if it has not, indeed, already.

Al–Nakba, then, was a testing ground for the strategies and policies Israel would adopt to enforce their occupation and settlement of Palestinian land. There seems no question of this: What began on the ground in December 1947 has continued since without interruption and is what we witness to this day in Gaza and the West Bank. From the beginning, Israel’s project of ethnic cleansing has been coldly calculated, deliberate, and strategic, matching in its execution—if not magnitude—the horrors that the Third Reich inflicted upon European Jews.

Zionism, to put this point plainly, destroyed Samia’s world—a secular multi-ethnic, and multi-religious world that had comfortably coexisted for centuries, even as various empires rose and fell around it.

Samia said:

Before 1948, it was secular in Palestine. We had Jewish neighbors. You couldn’t tell who was Christian, or Muslim, or Jewish. There was no fanaticism before ’48. There were no dress codes. The colonial powers destroyed that. They colonized the country and the faiths.

A moving account of the destruction of Lydda and Ramleh is available, among other places, in Ilan Pappé’s book The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine, (Oneworld, 2006). The de–Arabization and subsequent Judaization of Palestine was long-planned and awaited only the right conditions. Without realizing or even intending it, the United Nations’ partition plan was the green light Ben–Gurion had been waiting for.

It seemed especially tragic as I listened to Samia, a living witness to al–Nakba, to recall again that generations of American Jewish and Israeli children have grown up propagandized in their day schools to believe a completely false and ahistorical narrative: that the land of Palestine was empty when European Jews migrated there. Irrationally, they have also been taught that Israel fought a heroic war for independence, while, in reality, Israel’s founding fathers drove Palestinians from their homes through horrendous acts of violence. It is a history intentionally erased from Israeli consciousness. This process of indoctrination simultaneously instills a deep fear and hatred of Arabs.

Palestinians are well aware of this, of course. “Israeli children are told, ‘Arabs are going to kill you,’” Samia said. “The educational curriculum in Israeli day schools is a brainwashing system, of children and the entire population, in Israel and also in the West.”

This process of indoctrination undermines, as it is intended to, any chance for a meaningful peace because the Israelis—to say nothing of their American supporters—are incapable of seeing and understanding reality as it is. They do not even know their own national history. It is all myth and lies.

It makes hope difficult for Palestinians because they know they are dealing with irrational actors—two nations that rely on brute force to impose their will. I was surprised by how frequently I heard the older generation of Palestinians remark—as if with genuine perplexity—on the conduct of Israel and the United States with the question: “Why do they do this?” And, “Who behaves this way?”

Many of the younger Palestinians I met no longer care to try to understand, or so it seemed to me. They know it is irrational to look for logic in America’s foreign policy and Israel’s conduct—beyond the imperatives of naked imperial ambition. Indeed, they feel utterly betrayed by the Palestinian National Authority and the Fatah party.

I had the opportunity on various occasions to observe and interact with IOF soldiers at checkpoints in the West Bank. They come across as extremely ignorant and frightened children. They are young, armed, arrogant, and afraid. A more dangerous combination I cannot imagine. These are the people with life and death power over the Palestinians.

I was surprised, but not altogether so, to hear with what vehemence Samia spoke of these matters, and the subtlety with which she parsed the relationship between Tel Aviv and Washington. “Israel is an outpost of the U.S. in the Middle East, but Israel is the boss,” she said. “No one has the guts to tell Israel, ‘No.’ Especially the colonial countries that created Israel.”

Palestinians pay close attention to what is happening in the wider world: This I found again and again to be so. And they know, even if many others elsewhere do not, that the situation is slowly changing in their favor. As a sign of the times: There are now Palestinian studies curricula and departments in universities, which has helped increase the visibility and legitimacy of the struggle for Palestinian rights and freedom. Many young Jews increasingly disavow Zionism while actively supporting Palestinian rights, especially in the United States. These are significant developments. More to the point: Any country that perpetrates a genocide cannot last, and many Palestinians believe that Israel will one day cease to exist.

They must survive and outlast Zionism, keeping their families and culture intact as they do so. This is the task as many Palestinians understand it, or so it seems to me. The knowledge that they are on the right side of history accounts, I believe, for the dignified patience I recognized in Samia and in so many of the Palestinians I met. That, and the Arabic practice of sumud, which is translated as “steadfastness.”

Above all, Palestinians have proven themselves resilient—creatively so. They continue to resist occupation and erasure. They have not disappeared. Israelis know, too, if unconsciously, that the question comes down in part to one of endurance. Israelis know that Israel is fragile, which explains much of their behavior, including the otherwise inexplicable need to always confirm the right of Israel to exist.

I may be wrong, but I have come to believe that many Israelis understand, even if they cannot admit it, that Israel is profoundly illegitimate. This psychic fracturing within the individual and society fuels Israeli violence and the acceleration of their seizure and settlement of West Bank land.

All apartheid states eventually fall. Will Israel take the U.S. with it? It was a question Samia answered without my needing to ask. “Israel will be the downfall of the United States,” she said. “It will be too late, if the United States wakes up at all.”