How Secret How Secret Global Trade Talks Can Destroy the InternetGlobal Trade Talks Can Destroy the Internet

Talks on the two biggest trade agreements in history are reaching critical stages, and none of us knows anything about them. Like it or not, this is ignorance by design: Months of negotiations across both oceans have proceeded in secret, even as these deals are intended to set many of the rules we live by in the global era.

Now it is time to draw our chairs a little closer to the action:

• A summit of lead negotiators for the Trans–Pacific Partnership convenes Tuesday for six days of discussion in Salt Lake City. The objective is to fast-track the TPP through Congress—no debate, no amendments—by year end. The Pacific pact is prelude to the Trans–Atlantic Trade and Investment Partnership, which the U.S. and the European Union began discussing earlier this year. Together, these deals will cover 60 percent of world trade.

Related: As Asian Economies Grow, American Influence Shrinks

• Wikileaks, the blabber-mouthing bane of technocrats, generals, pols, and diplomats the world over, has just released the draft of a key chapter in the TPP’s working document. It covers “IP”—techno-speak for intellectual property—and it is a first-ever window into what is in store.

Are you ready for internet companies required (“legal incentives” is the phrase, Article QQ. I.1) to police those posting material on their infrastructure? What about supra-national statutes that take precedence over standing legal systems in matters such as copyright, patents, genetically modified food, and crop chemicals?

The TPP has been cock-eyed since talks began last January. The most obvious flaw: China is excluded, which is like conducting a symphony without the strings and brass. The inference, noted previously in this space, is that the pact is intended to project American neo-liberalism into Asia as part of a “contain China” policy rooted in the Cold War and so stale it can only crumble the instant it is exposed to air.

In many respects, the IP draft Wikileaks released a few days ago confirms the thought that the TPP will draw battle lines in the Pacific region that need not be there. It is a rare document in that it contains the working proposals and objections of all 12 negotiating nations.

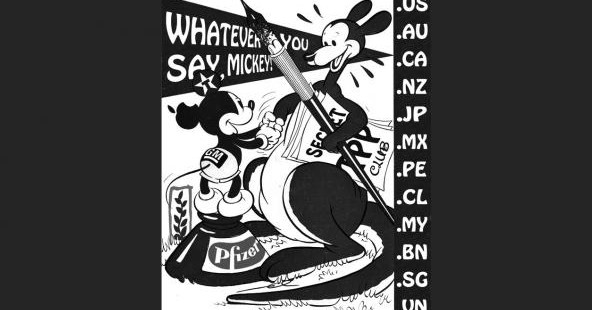

“AU” is Australia, “SG” is Singapore, “VN” is Vietnam, “CL” is Chile, and so on. It makes for thick-as-a-brick reading, almost every phrase nitpicked by one or another delegation, but you see who lines up with whom and what the sticky issues are. Often but by no means always, it is the Americans, Australians, and New Zealanders—Western civilization—against the rest.

Related: US-EU Trade Deal—Obama’s Ambitious Gamble

Wikileaks got a hold of this document after the 19th round of talks held in Brunei last August. What we have is what will be on the table in Salt Lake this week.

The U.S. and Japan will propose that a product can be patented even if it is just a clever twist on other products and “does not result in improved efficacy.” Everyone else at the table opposes that proposal (Article QQ.E.1). Australia wants marketing approval of agricultural chemicals in one country to count in other countries; the Chileans and Mexicans are tough talkers on this point (Article QQ.E.XXX).

The big stuff on the IP side concerns the internet and digital technology. And it does not come out well by the look of the draft. Service providers are to be held responsible for the content of what subscribers upload, identify transgressions such as copyright infringement, kick the stuff off the system, report the offenders, and stand liable for punishment if they miss anybody (Enforcement, Section 1).

Several problems here. Costs are one, service delays another. My big gripe is the incessant habit, evident in many places, of blurring what is private and what is public. Silicon Valley people, in my view, are challenged in matters of civic consciousness; it will not do if they are patrolling blogs, web sites, and the like. At the vanishing point, the web will turn to pablum.

The line among the Wikileaks folk and other practiced objectors is that the leaked document suggests the TPP will “trample over individual rights and free expression, as well as ride roughshod over the intellectual and creative commons,” as Wikileaks founder Julian Assange puts it. You cannot flick away the thought, but it is more complicated.

Some deserving questions are addressed. Counterfeiting is one, although the Americans want to take this much further than everyone else, criminalizing the practice in nations where copying is by tradition looked upon differently than in the West (Article QQ.H.4.Y). The document also promises “national treatment,” meaning foreign traders and businesses are to be treated equally in all nations, and the need to preserve “a rich and accessible public domain.”

All good. But the positives too often read as boilerplate, as if they were inserted for the sake of political correctness. These are the only sections without dense comment from the delegations because there are no teeth in them.

Related: EU/US Say Trade Deal Won’t Pander to Big Business

Agreements such as the TPP and the U.S.–E.U. version of same have virtue en principe. They can be mechanisms for drawing the community of nations closer, as the E.U. is (which is why I favor it and the euro). But they are also worrisome and, in my view, fated to fail, primarily because of the way they distribute power.

In the TPP’s case, the classic English conception of free trade is elevated to idolatry, and it will not hold. Economic systems and all institutions within them have cultural dimensions. In the European case, there are social-democratic traditions to think about; in Asia, a community ethos colors everything from tax regimes to the way stock markets work.

Our new, all-encompassing trade agreements, assuming they pass among negotiating nations, will have an enormous impact. Even Congress has had limited, supervised access to the evolving texts. The only ones privileged to observe the progress have been some 600 “trade advisers,” who include executives of multinationals such as Walmart, Halliburton, Monsanto, and the like. This is not only impudent; it is simply wrong.

The argument for secrecy is evident in the document we now have. These talks are so complex and nuanced that public exposure would mean nothing would ever get done.

But when you consider the secrecy against the Wikileaks document, you come up against a fundamental problem still awaiting a solution: Is the globalization process of necessity in conflict with democratic procedure?

If we get some sliver of access in Salt Lake this week, maybe we will have the makings of an answer.