China’s European Moment Has Arrived

The simplicities of the postwar order have just begun to pass into history, writes Patrick Lawrence.

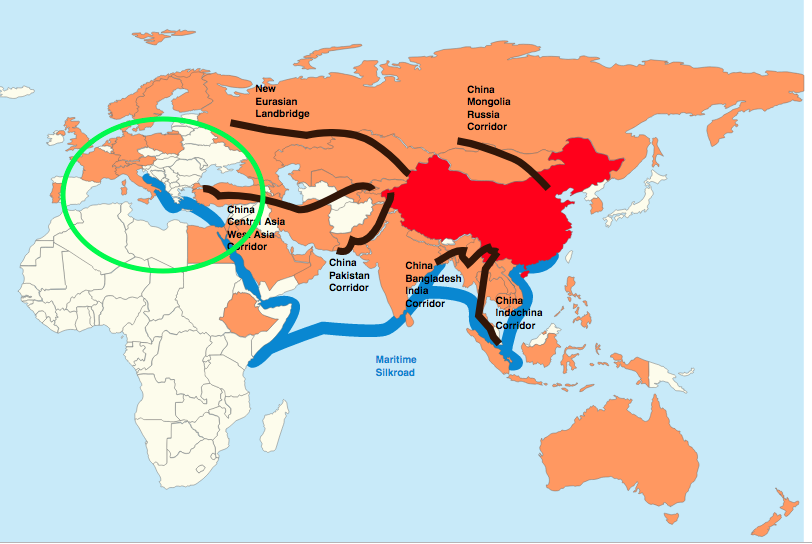

It would be difficult to overstate the importance of Xi Jinping’s visits to Rome, Paris and Monaco last week. In bringing his much-remarked Belt and Road Initiative to the center of Europe, the Chinese president has faced the Continent with the most fundamental question it will have to resolve in coming decades: Where does it stand as a trans–Atlantic partner with the U.S. and — as of Xi’s European tour — the western flank of the Eurasian landmass? The simplicities of the postwar order, to put the point another way, have just begun to pass into history.

In Rome, the populist government of Premier Giuseppe Conte brought Italy into China’s ambitious plan to connect East Asia and Western Europe via a multitude of infrastructure projects stretching from Shanghai to Lisbon and beyond. The memorandum of understanding Xi and Deputy Premier Luigi Di Maio signed calls for joint development of roads, railways, bridges, airports, seaports, energy projects and telecommunications systems. Along with the MoU, Chinese investors signed 29 agreements worth $2.8 billion.

Italy is the first Group of 7 nation to commit to China’s BRI strategy and the first among the European Union’s founding members. It did so two weeks after the European Commission released “EU–China: A Strategic Outlook,” an assessment of China’s swift arrival in Europe that goes straight to the core of the Continent’s ambivalence. Here is the operative passage in the E.C. report:

“China is, simultaneously, in different policy areas, a cooperation partner with whom the E.U. has closely aligned objectives, a negotiating partner with whom the E.U. needs to find a balance of interests, an economic competitor in the pursuit of technological leadership, and a systemic rival promoting alternative models of governance.”

There is much in this document to chew upon. One is the mounting concern among EU members and senior officials in Brussels about China’s emergence as a global power. This is natural, providing it does not tip into a contemporary version of the last century’s Yellow Peril. At the same time, the Continent’s leaders are highly resistant to the confrontational posture toward China that Washington urges upon them. This is the wisest course they could possibly choose: It is a strong indicator that Europeans are at last seeking an independent voice in global affairs.

Looking for Unity

They are also looking for a united EU front in the Continent’s relations with China. This was Emmanuel Macron’s point when Xi arrived in Paris. The French president made sure German Chancellor Angela Merkel and E.C. President Jean–Claude Juncker were there to greet Xi on his arrival at the Élysée Palace. The primary reason Italy sent shockwaves through Europe when it signed onto Xi’s signature project is because it effectively broke ranks at a highly charged moment.

But unity of the kind Macron and Merkel advocate is likely to prove elusive. For one thing, Brussels can impose only so far on the sovereignty of member states. For another, no one wants to miss, in the name of an E.U. principle, the opportunities China promises to bring Europe’s way. While Macron insisted on EU unity, he and Xi looked on as China signed contracts with Airbus, Électricité de France, and numerous other companies worth more than $35 billion.

There is only one way to read this: Core Europe can argue all it wants that China is unrolling a divide-and-conquer strategy, but one looks in vain for on-the-ground resistance to China’s apparent preference for bilateral agreements across the Continent. On his way home, Xi stopped in Monaco, which agreed in February to allow Huawei, China’s controversial telecoms company, to develop the principality’s 5G phone network.

In numerous ways, Italy was fated to demonstrate the likely shape of China’s arrival in Europe. The Conte government, a coalition led by the rightist Lega and the Five-Star Movement, has been a contrarian among EU members since it came to power last year: It is highly critical of Brussels and of other member states, it opposes EU austerity policies, it is fiercely jealous of its sovereignty in the EU context, and it favors better ties with Russia.

Closer to the ground, the Italian economy is weak and inward investment is paltry. Chinese manufacturers have made short work of Italian competitors in industries such as textiles and pharmaceuticals over the past couple of decades. A map, finally, tells us all we need to know about Italy’s geographic position: Its ports, notably Trieste at the northern end of the Adriatic, are gateways to the heart of Europe’s strongest markets.

As the westward destination of Xi’s envisioned Belt and Road, Europe’s economic and political relations with China were bound to reach a takeoff point. The accord with Italy, Xi’s European tour and an EU–China summit scheduled to take place in Brussels on April 9 signal that this moment has arrived.

Shift in Relationship

But it is not yet clear whether Europeans have grasped the strategic magnitude of last week’s events. In effect, the Continent’s leaders have started down a path that is almost certain to induce a shift in the longstanding trans–Atlantic relationship. In effect, Europe is starting — at last — to act more independently while repositioning itself between the Atlantic world and the dynamic nations of the East; China first among them by a long way.

No European leader has yet addressed this inevitable question.

Let us not overstate this case. Trans–Atlantic ties have been increasingly strained since Barack Obama’s presidency. President Donald Trump’s antagonisms, most notably over the Paris climate accord and the Iran nuclear agreement, have intensified this friction. But there is still no indication that any European leader advocates a rupture in relations with Washington.

Can U.S.–European ties evolve gradually as China’s presence on the Continent grows more evident? This is the core question. Both sides will determine the outcome. The Europeans appear to be preparing for a new chapter in the trans–Atlantic story, but there is simply no telling how Washington will respond to a reduction in its long-unchallenged influence in Western European capitals.

There is one other question the West as a whole must face. The E.C.’s “strategic outlook” terms China “a systemic rival promoting alternative forms of governance.” There are two problems with this commonly sounded theme.

First, there is no evidence whatsoever that China has or ever will insist that other countries conform to its political standards in exchange for economic advantage. That may be customary practice among Western nations and at institutions such as the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank. It is not China’s.

Second, as we advance toward a condition of parity between West and non–West — an inevitable feature of our century — it will no longer be plausible to assume that the West’s parliamentary democracies set the standard by which all others can be judged. Nations have vastly varying political traditions. It is up to each to maintain or depart from them. China understands this. So should the West.