China Grows Impatient with the Barbarian of North Korea

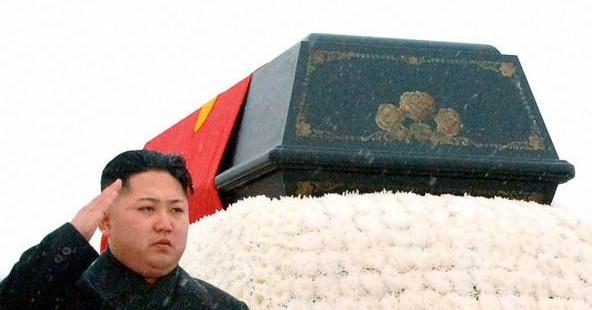

North Korea’s leader has a baby face and a weird haircut and exhibits the whims of an unsupervised kid at Disneyland. He’s thrown tantrums before, threatening to fire nuclear missiles at the United States, executing a female musical group, and declaring war on South Korea. We have to forget all this now.

Now, the 30-something Kim Jong Un has just made a grown-up’s mark on global politics.

Related: How North Korea Starved Its People for a Nuke

Taking a side on North Korea has long been like shooting at the side of a barn. The leadership purge Kim has just revealed changes nothing in this regard. It was gruesome as all get-out, culminating in the execution of his aunt’s husband and his apparent mentor, Jang Song Thaek. Pyongyang is Leninist, ends justifying any means, and positively Venetian in its treacheries.

The focus falls on the nations identified with the “six-party” talks desultorily under way since North Korea bailed on the Non–Proliferation Treaty in 2003—China, Japan, South Korea, Russia, and the U.S. What are these allies/enemies/untrusting neighbors going to do now?

Two headlines write themselves instantly. One is, “Kim Jong Un to sunshine policy: Drop dead.” The other is, “Kim likely to take nuclear option.” Both stories are page one above the fold: They change the balance of power in Northeast Asia.

The sunshine approach—a gradual opening to North Korea based on common economic interests—is classic Asian diplomacy—the strategy developed by the late Kim Dae Jung, South Korea’s first democratic president. South Korea’s conservative president now, Park Geun Hye, has tried a less heartfelt variation called “trust building.”

One of Kim Jong Un’s curious decisions last week was to identify his suddenly absent uncle as a reformist using economic temptations to build a political base. Sunshine may one day prove out, but for now, a long, dark cloud hovers.

Related: North Korea Executes Leader’s Power Uncle in Public Purge

As to the nuclear question, toughness and fear make an intractable combination, and the young Kim evinces both times ten. His father, Kim Jong Il, seemed to desire occasionally a deal on weaponizing nukes.

Now, when we have intel suggesting new activity at missile and nuclear sites—well, as Mencken once observed, “A pessimist is someone in possession of all the facts.”

On Sunday, ABC’s This Week with George Stephanopoulos aired an exclusive interviewwith Secretary of State Kerry. Kerry stressed the need to bring together the five powers active on the North Korea question and make denuclearizing in the Korean peninsula a very high priority. Both ambitions are problematic now. The first will require diplomatic acceptance that power positions are changing; the second requires a Hail Mary pass.

China has viewed North Korea as a useful buffer since Mao sent troops into the peninsula to stop, as he did, Douglas MacArthur’s advance against Kim Il Sung, grandfather of the man shooting his relatives. But Beijing has a past-or-future question on its hands. President Xi Jinping is a chest-out sort who is into asserting China’s power for all to see. A buffer state seems an outdated technology.

This could work well, you may say. But those holding this view are likely to be proven wrong.

China’s indulgence of the North has made possible conversations otherwise out of the question. But it has been impatient with Kim’s stupidities since he took power two years ago this week. And now China may modulate away from paternal tolerance toward a toughened approach that would speed progress (if ever there has been any).

Related: U.S. Relies on China’s Ability to Control Kim

The take-home here: China can get the new Kim to cool it, as it appears to have done when things grew tense earlier this year, but the new reality is that it will never deliver a nuclear-free North. Nuclear-capable but not weaponized is probably the new goal.

It is a reset with the rise of every Kim in North Korea. Each arrives with profound misgivings as to the outside world, especially the West and the Chinese, and these echo back many centuries into history. No Kim is in power quite long enough to gain the confidence needed to get beyond the “hermit kingdom.”

Tokyo, Tonto to Washington’s Lone Ranger for six decades, could easily complicate this picture further. Prime Minister Shinzo Abe is eager to get Japan back on the Pacific map as a military presence—and no bad thing, in my view, if Japan starts thinking for itself. But tensions between Japan and China being as they are, Kim-the-latest-hard-liner could worsen them.

Abe is a credentialed anti–Communist and nationalist, and he likes shooting at the sides of barns to demonstrate his aim. With no sunshine option to restrain him, he could be drawn into pushing past Beijing (and Seoul) in the name of Japanese reassertion: As targets and barns go, he now has a big red one. And there may go the neighborhood.

Related: China’s Bold Power Play Pushes Asia to the Brink

How does Washington navigate such tricky currents? Just two major veins to explore at this point. One is to adjust goals. Freakish as the experience may be, it is time to look at the world as it appears from Pyongyang. No one can make the sun shine, but in a region the U.S. had everything to do with creating, there are possibilities.

The other necessity now is to avoid letting the policy hawks re-emerge in the long-running battle between them and the acolytes of KDJ. There is no argument for it.

It was fruitless when Defense Secretary Hagel sent B–52s into disputed airspace off the Chinese coast a couple of weeks ago, and a huge mistake when he wheeled missiles aimed at North Korea into place earlier this year. In the latter instance, he had to step back within days.

Big powers have to act big to be big. It cannot be hard to act bigger than Kim Jong Un, and maybe some others now throwing weight around across the ocean.