“In Ukraine, a war for memory.”

To destroy the shared past of a people is to go some way toward destroying a people—the coherence and solidity of their identity, their ability to think and act collectively, their collective confidence in themselves, altogether their place in the world. It is among the most vicious methods known to aggressor armies, imperial powers, and dictators—psychologically vicious, vicious because effective—of attacking the psyches and souls of others in the course of violent campaigns to dominate them.

Pierre Nora, the honored French scholar of history and identity, termed the places where people preserve their pasts lieux de mémoire, sites of memory. It is these that are attacked, sooner or later, when one or another kind of power seeks to destroy or conquer other people. You saw this during the Cultural Revolution, when Red Guards defaced as many monuments to China’s past as they could. You have long seen this in the Israelis’ aggressions against Palestinians. And you have seen it this past decade as the Kiev regime continues its war against the people of Donbas.

This war on memory, as Guy Mettan terms it, is in our view a pernicious, quite significant dimension of ethnic cleansing. In Part 2 of his “Report from Donbas,” Mettan takes us to some of the places where this war is waged to show us how the people of Donetsk and Lugansk, once again Russian by choice, defend their sites of memory as a matter of defending themselves.

The Floutist published the first part of this exceptional series 11 May. We are pleased to welcome Mettan, the distinguished Swiss journalist, back into our pages. Part 1 of his Report can be found here.

—The Editors.

Guy Mettan

It is now two years and several months since the Russian military began its intervention in Ukraine. And between Russia and the West, between the Ukrainians in Kiev and the former Ukrainians who have become Russians again, the battle is not just a military struggle. It is also a struggle in defence of memory against those who would obliterate it.

In the West, the 80th anniversary of the D–Day landings on 6 June will be commemorated without the Russians. This is an official if symbolic denial that the victory over Nazi Germany was first and foremost a Soviet victory and that Operation Overlord could not have succeeded without the Red Army’s Operation Bagration in the east, to hold off German tank divisions.

Attempts to erase the past in this manner are not at all new. One finds cases of it throughout history. But in the lands to Europe’s east and the Russian Federation’s west it has greatly intensified since 2014, a decade back, when, some months after the U.S.–cultivated coup in Kiev, the Western powers marked the 70th anniversary of the D–Day landings and refused to invite Russians to the ceremonies held on the Normandy beaches—this while inviting representatives of the former enemy, among them German Chancellor Angela Merkel.

Across Eastern Europe, the Baltic states, and in Ukraine in particular, history is being turned upside down. Historical statues and war memorials honouring those who defeated the Reich in the Second World War are being demolished to erect steles, inscribed stone pillars, that commemorate not the Soviet’s hard-won victory but the victims of the Soviets. These monuments are also intended to mark the glory of the nationalists who fought alongside the Nazis and massacred Jews, such as Stepan Bandera, Yaroslav Stetsko, and Roman Shukhevich.

Every day, monuments are taken down and others erected in their place—on the sly, in the silence of the Western media. We seem to forget, to take but one example of many, that the Treblinka death camp was run by a group of some 20 German SS troops and that the exterminations were carried out by a hundred Ukrainian and Lithuanian guards.

This rewriting of history amounts to a war on the past of a people. And if it is waged not on battlefields but at sites of memory, the outcome of this struggle is comparably important. To destroy the collective memories of a people is to destroy their common identity. In this way it also destroys their understanding of their place in the world and their ability to act effectively—and so their ability to go forward. If you have no past you have no future, it has been said: This is the ultimate objective of those who attack the shared memories of others.

None of this has gone unnoticed by the people of Donbas. And, true to their motto, “Never forget, never forgive,” they are in response redoubling their commemorative faith and monuments to fallen heroes.

A typical example of this struggle are the annual commemorations of the Holodomor, held each fourth Sunday of November, as the European Parliament mandated in 2008. The Holodomor is the Ukrainians’ name for the famine unleashed by Stalin against the peasantry in 1932. These events occurred mainly in 1932–1933 and were the result of Stalin’s desire to advance the collectivization of the economy. In this cause he confiscated the peasants’ incomes to finance the Soviet Union’s industrialization following the financial boycott of the Western capitalist countries.

But as a memorial the Holodomor commemoratives are incomplete. They attribute this massacre by famine solely to the Russians. Ukrainians are depicted as its sole victims, even though the famine also affected southern Russia and Kazakhstan and was orchestrated by a Georgian, Stalin, and executed by a Pole, Stanisław Kossior, who ruled Ukraine at the time. The present Ukrainian authorities have never acknowledged the collaboration of local and regional Communists. In the Ukrainian narrative of the tragedy, all responsibility for it has been and continues to be projected onto Russia and Russians, even though ethnic Russians played a minor role in that tragedy.

During the two last days of my trip in Donbas, we visited a dozen of the memorials established to commemorate the victims of the slaughters, massacres, and wars that have occurred on the territory over the last century. These are countless. You can find them in cities, in the countryside, and in small villages. This is why, during two full days, we travelled here and there, on small roads and large, throughout the two republics, Donetsk and Lugansk, to visit these testimonials of past dramas.

■

Perhaps the most disturbing of these memorials is located near the shaft of Mine No. 4/4–bis in Donetsk. The site was once a coal mine and lies not far from the centre of the city. Mines are everywhere here. The entrance, very sober, appears to be to the side of an ordinary street road of an ordinary suburb. There are no large advertisements for it.

I’d never previously heard of Mine No. 4/4–bis, and I suspect you haven’t either. It doesn’t appear in any of our history books and can’t be found in Wikipedia. This why it is maybe the most disturbing place of death that I visited. In Auschwitz or Babi Yar, in Kyiv, you know what you are facing, and you expect to be moved. But here, you have to add the element of surprise.

It is estimated that 75,000 to 102,000 people were massacred at 4/4–bis from the end of 1941 to September 1943, two or three times as many as at the better documented massacre in 1941 at the ravine in Kiev known as Babi Yar. The entire Jewish community of Donetsk (called Stalino at the time) was thrown into the pit, along with tens of thousands of others.

The Kiev government ignored the 4/4–bis memorial after 1991, when Ukraine declared its independence, because it disrupted official narratives and concerned only Russian-speaking people in the east of the country. But for the past year the site has been brought to life again. The restoration work, not quite finished, is still under way. The site is, accordingly, not yet open to the public. But the visible parts are quite impressive: There are prominent sculptures, a wall honouring those killed, landscaped gardens and trees.

A visit to No. 4/4–bis is all it takes to understand why the people of Donbas rose up against Kiev in April 2014, when the regime that emerged from the U.S.–backed Maidan coup wanted officially to ban their language while sending the heirs of their forebears’ executioners to suppress them. This region has a strong tradition of resistance to any kind of invaders, from German Nazis to west–Ukrainian ultranationalists in Nazi–style uniforms. If No. 4/4–bis is about remembering, it is also about determination.

You can destroy monuments, but not memories.

■

Seventy kilometres northeast of Donetsk, in the direction of Bakhmut, in the province of Horlivka, the monumental Savur–Mohila cenotaph is another testimony to the battles of the last century. It is erected at the top of the highest hill in the Donbas, on the site of one of the great clashes of the Second World War. That took place in July–August 1943, at the same time as the famous tank battle of Kursk, which was to break the Wehrmacht.

A broad stairway up the hill with a huge spire at the top was built here in 1963. Seven decades later—in August 2014, six months after the coup in Kiev—the hill was the scene of a bitter battle between separatists and units of the Ukrainian Armed Forces. The monument was hit hard during the battle. When the separatists retook the hill, led by Alexander Zakhartchenko, their prestigious leader, it was a definitive victory for the Donetsk republicans.

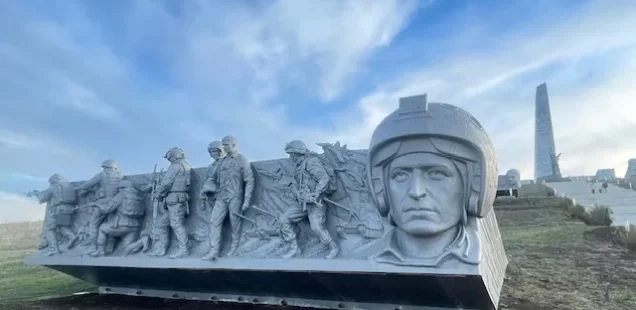

But the fighting had devastated the Savur–Mohila site. And after the Russian military operation began in February 2022, President Putin ordered it rebuilt to commemorate two wars—the Great Patriotic War of 1941–1945 and the Donbas Liberation War of 2014–2022. On either side of a walkway that leads to the spire on top of the hill, large sculpted steles celebrate the heroes who died for the freedom of Donbas from 1941 to 2022. In this important way, the present is anchored in the past.

This battle to preserve memory against its destruction is probably most intense in Lugansk. I’m welcomed there by Anna Soroka, a historian who has been fighting in the republic’s regiments since 2014.

The first monument she shows me commemorates the 67 children killed by Ukrainian militias from the Kraken and Aïdar battalions, both of them neo–Nazi, who tried to take the city in 2014, failed, and then proceeded to shell it until the Russian intervention in 2022. It was built in the middle of a park that serves today as a kindergarten. Several kids were killed there by targeted Ukrainian shelling—targeted, surely, as the surrounding buildings were not hit.

Children are the objects of an unrelenting information war on both sides. The Ukrainians have filed war crimes charges against the Russians, and the International Criminal Court has indicted Vladimir Putin and the head of Russia’s children’s affairs agency, Maria Lvova–Belova, for allegedly kidnapping Ukrainian children. Western propaganda repeats these accusations over and over, in media and in the cinema: A full-length documentary, 20 Days in Mariupol, directed by Mstyslav Chernov, Michelle Mizner, and Raney Aronson–Rath, featured these allegations and has just won this year’s Oscar for best documentary.

Western media reports naturally fail to pass on the point of view of the inhabitants of the Donbas—who say it is the Ukrainians who are taking children hostage. There is, in fact, a volunteer organization in Ukraine called the White Angels, modelled on the infamous Syrian White Helmets, who, as you will recall, were far from the neutral rescue workers they posed as and, in fact, were covertly funded by Western intelligence and acted in behalf of jihadist groups.

These White Angel detachments were formed in February 2022 by a certain Rustam Lukomsky. The Western (or Western-backed) press has mentioned them on several occasions. The Kyiv Independent (24 March 2024), Le Monde (7 February 2023), the BBC (30 January 2024) are among the media that have reported on this group. “Amid the thud of explosions and rattle of gunfire,” a typical report reads, “a special police unit called the White Angels goes door-to-door helping evacuate the town’s remaining civilians.” Lukomsky, whose background remains unclear, is portrayed invariably as a hero of these operations.

For those in Donbas, the White Angels are something very different. The group’s aim, residents here say, is to force parents in front-line areas to separate from their children under the pretext of protecting them. The children are thus isolated and “taken to safety” in the rear, where they are used as a means of blackmail against their families.

These families are in this way torn between two equally unbearable choices: Either they abandon their homes to join their children, or they remain near the front and are forced to collaborate with the Ukrainian army, which invites them to denounce or sabotage the movements of the Russian army.

One can only imagine the distress of parents faced with such perverse coercion. Testimonies, such as those of Olga V. Zubtsova, from Bakhmut, and Igor Litvinov, from Avdiivka, confirm this version of events. “In Avdiivka,” Igor says, “the ‘White Angels operated completely unhindered and, in the guise of good intentions, offered to evacuate families with children on the Ukrainian side. When the parents refused, they threatened to take the children away.” There are countless rumours circulating on social networks, it bears mentioning, accusing these so-called White Angels of fuelling paedophilic crime networks and child trafficking. But this remains to be proven.

■

The second Lugansk monument is located in a wood just outside the city. Like Donetsk’s Mine No. 4/4–bis, it does not appear on our search-engine result pages. And like Donetsk’s Mine No. 4/4–bis, it commemorates the site of the massacre of Lugansk’s Jewish community. About 3,000 mainly Jewish women and children and 8,000 adults of various faiths were executed here by the Nazis during the Wehrmacht’s occupation of the city.

“We can’t understand why, today, Kiev is honouring the descendants of those who killed so many of our people during the Second World War,” Anna Soroka, the historian and soldier, tells me as we tour the site. It has been abandoned to brambles since 1991, when Luhansk Oblast, which was previously part of the USSR, became part of Ukraine following the referendum on independence. The new authorities of the republic decided recently to cut the bushes and to restore it.

A little further along, on the other side of the road, the republic’s authorities have erected a vast memorial honouring the combatants and civilians killed in the 2014–2022 war. Nearly 400 graves are lined up on either side of a walkway that leads from a Rodin-inspired statue near the entrance to a column and a small chapel at the centre of the site.

Anna personally knew most of the people buried here.

We stop at the grave of a man named Ivan Selikhov.

On 5 May 2014 Ukrainian militias took Ivan from his home and executed him with a bullet to the head—making an example of him because his son had joined the republicans. Before his body was interred here, his neighbours were initially forced to bury him in his garden.

The site, which is exactly where a battle took place that summer, pays tribute to the 397 killed, “victims of Ukrainian aggression”—workers, trench diggers, teachers, schoolchildren, doctors, nurses, and patients hit by the bombardment of their school and hospital, during which the dead numbered 169.

On our way back into Lugansk we pass a large monument to the Soviet soldiers who liberated the city in 1943. And then, after a few more miles, we come upon a Ukrainian tank decorated with flowers and set on a concrete base beside the freeway: Local inhabitants put it there as a reminder that this tank bombed their homes 10 years ago. Below, there is a field still littered with mines where people are strongly advised against walking.

■

The last monuments on this mournful tour of the city are perhaps the most emblematic of the tragic fate of Donbas over the last hundred years. These comprise the Hostra Mohyla memorial, which is set on a small hill southeast of the city.

Here, a number of different monuments commemorate the communities wiped out over many decades. Various monuments and steles cover the hillside, each erected by a different community or civic organization; among these, the Orthodox Church commemorates its members and believers.

The largest of these memorials, which crowns the top of the complex, holds the key to the psychology of the region’s inhabitants. I studied it carefully.

It features four giant statues of soldiers, heroes-in-arms of the four wars that mark the collective consciousness of Donbas: There is a bronze fighter from the Civil War of 1917–1921, a Soviet soldier from the Great Patriotic War, a militant from the anti–Kiev resistance of 2014–2018, and, finally, a fighter from the war of liberation of the oblast that began in 2022 and continues to the present day. Again, the past lives on and informs the present.

More erasure: For the Hostra Mohyla site, as for others, there is absolutely no information to be found on Western search engines despite its popularity with the locals. Google and Wikipedia ignore or have banned these sites from their directories. Only the German Stiftung Denkmal für die ermordeten Juden Europas, the Foundation Memorial to the Murdered Jews in Europe, provides any information on the Jewish victims.

It is easy to understand, after a brief tour of these sites, built to keep memory alive, why Russia, and its new citizens in what were formerly the eastern provinces of Ukraine, will never give up their fight against Kiev and the West until they win it. The dull rage that seizes them when they think that the Western powers wanted, through Ukrainians, to wipe them off the face of the earth, literally and figuratively, will disappear only with what they consider to be their victory. To defend their past, to preserve memory against those who would destroy it, is to defend their right to live in their lands.

This report appears simultaneously in Arrêt sur info, in French, and in the Swiss journal Current Concerns. Die Weltwoche has published German-language translations of Parts 1 and 2 together.

Guy Mettan is an independent journalist in Geneva and a member of the Grand Council of the Canton of Geneva. He has previously worked at the Journal de Genève, Le Temps stratégique, Bilan, and Le Nouveau Quotidien. He subsequently served as director and editor-in-chief of Tribune de Genève. In 1996, Mettan founded Le Club suisse de la presse, of which he was president and later director from 1998 to 2019.

Two of Mettan’s books, Europe’s Existential Dilemma: To be or not to be an American vassal, and Creating Russophobia: From the Great Schism to anti–Putin hysteria, are available in English from Clarity Press.

I strongly recommend Mr Mettan’s book ‘ Creating Russophobia: From the Great Schism to anti–Putin hysteria’.