“‘It is.'”

A novelist confronts the siege in Gaza.

The Floutist is pleased to publish for the first time, an excerpt from Peter Dimock’s novel in progress. This “fragment,” to use Dimock’s term, is nothing less than a literary meditation on the impunity of State violence.

Its specific object of contemplation is the case filed on 13 November in U.S. federal court in California against President Biden, Secretary of State Blinken, and Secretary of Defense Austin for their complicity in and failure to prevent Israel’s genocide in Gaza.

Dimock introduces readers to the three main characters from his previous novel, Daybook from Sheep Meadow: Tallis Martinson, his twin brother, Christopher Martinson, and Tallis’s daughter, Cary Martinson Winslow. This excerpt continues their story. Tallis, having suffered a nervous breakdown, has been hospitalized in a state of almost complete catatonia. Christopher and Cary visit him frequently in the hope that he will one day recover.

Unconventional and entirely original in its conception and execution, the story is defined by a shared pursuit: Each character practices a common “meditative method,” keeping a journal, and sharing their experiences. The intent of this contemplative practice is the liberation of language, and therefore also mind and thought, from the all-encompassing domination and violence of empire.

Dimock has long been preoccupied with the power of language. It is only when language and thought are freed that moments of “historical justice” become possible—however fleeting these moments may be and even if they are experienced nowhere else but within the mind of the person practicing this meditative technique. Understanding, as Dimock does, that language itself is one of the many casualties of empire, any hope we have of surmounting the existential crises we now face necessarily depends upon freeing language from the shackles of late-imperial capitalism.

Dimock’s narrative device—the “meditative method” that consumes the three characters—grapples with the reality of our time, scarred as it is by the brutality of empire, the legacies of colonialism and racism, endless warfare, and now this: the genocide in Gaza, conducted in real time for all the world to see—and our collective failure to stop it.

Described as an experimental novelist, Dimock pushes the boundaries of language and narrative structure to create a new literary form wherein history, philosophy, court rulings, cultural artifacts, and fiction are juxtaposed, contemplated, ordered, and reordered in a kaleidoscopic mosaic of language and imagery.

This is not novelty for novelty’s sake. Dimock’s intent is not to shock or offend, even less is it to entertain or distract. His purpose is to create a literature and language capable of addressing the moment in which we live, with all of its violence, horror, and despair. To which I add: hope—the hope that Dimock’s work and indeed his very effort embodies.

Dimock’s work is complex. In all three of his published novels, as in this extract, Dimock defies traditional Western forms and trajectories. Here you will find curious symbols and references to music and musical notation, along with passages from Emmanuel Levinas, quotations from Karl Marx, and much else. He has added endnotes and an appendix to facilitate the reader’s understanding of and engagement with the meditative method as described.

Rather than offer you a compass and map by way of this introduction, I invite you instead to enter and explore this superbly and richly evocative narrative landscape as you would a poem, attentive to all that it promises to evoke in you.

The Floutist published a webcast interview with Dimock when his previous novel came out. He is that rarest of voices in the literary world. He is an artist doing what the best of artists do, enabling us to see and understand—and subsequently respond to—the world in an entirely new way. Which is to say, his work leaves us changed.

This is not a work to be read as one would the kind of political commentary generally found on The Floutist. Let yourself swim in these deep waters—and drown if you must. As I have.

Bon voyage!

—C. M.

“‘It Is.’”

A fragment from a novel.

Peter Dimock

"It is every individual’s obligation to confront the current siege in Gaza. . . ."

—Half-sentence from United States District Court Judge Jeffrey S. White’s Court Order granting dismissal and denying plaintiffs’ motion for a preliminary injunction in Defense for Children International-Palestine, et. al., v. Joseph P. Biden, et. al., January 31, 2024

But today is a different day. How do we read the judge’s ruling now or act on it having read it again within this last half-hour?

No one doubts that a novel needs a language of continuity for thought’s coherence. Surely that’s not too much to ask of the history we are living—just a pattern with which to say how this thought and then this day connects with any other.

My twin brother is the American historian Tallis Martinson. He wrote histories about civil—military relations from the time of our republic’s founding to the present day. My name is Christopher Martinson. I was my brother’s editor and tried to make his sentences sing.

…but it is also this Court’s obligation to remain within the metes and bounds of its jurisdictional scope. . . There are rare cases in which the preferred outcome is inaccessible to the Court. This is one of those cases. [Despite the undisputed evidence before this Court], [t]he Court is bound by precedent and the division of our coordinate branches of government to abstain from exercising jurisdiction in this matter. Yet, as the ICJ has found, it is plausible that Israel’s conduct amounts to genocide. This Court implores Defendants to examine the results of their unflagging support of the military siege against the Palestinians in Gaza.

These sentences—and half-sentence—are also from Jeffrey S. White’s January 31, 2024, United States District Court Order. It grants dismissal and denies Plaintiffs’ motion for preliminary injunction in a case brought against President Biden for his failure to enforce his peremptory, binding obligation under international law to prevent, prosecute, and punish the crime of genocide.

When institutions fail, must people fail too?

A theme for a novel in progress.

Then this thought for a novel’s craven lack of a coherently narrated point of view: this modern, profitable, liberal perfection of rule—the absolute violence (given the necessity for order) of empire’s deniable, entitled impunity outside and beyond any practiced duration of worded thought or speech. These pleasured rhythms for the comforts of impunity’s success beyond any democratically deliberative content or context of a sustainable common good.

Unlike Judge White I have ceased to implore my president. I wrote him twice. But every day I obey the judge’s order to discharge my individual obligation “to confront the current siege in Gaza.” I do so by learning and reciting—then practicing (as well as I am able)—my brother’s “Meditative Method for Creating Durations of Historical Justice.” It was from the meditative exercises Tallis devised that he, I, and his daughter Cary Martinson Winslow now hope to create a common ground for future well-being. All three of us have decided to practice the method and discuss our results with each other when we get together each month in the dayroom of the long-term psychiatric care facility where Tallis now resides.

On February 1, 2024, I began to incorporate fragments from Judge White’s Order of dismissal of US Federal Case No. 23-cv-05829-JSW into my brother’s memorization template. I cannot, of course, yet vouch for the quality of the results issuing from my decision to do this.

Below are dated excerpts from notebooks in which I recorded my daily practice of my brother’s method.

But first let me explain my brother’s circumstances to give you a better idea of how Tallis, I, and Cary originally decided to practice—and then convene to discuss—his method together. In 2015 Tallis voluntarily committed himself to a long-term psychiatric care facility as the result of a severe mental breakdown following what Tallis considered his failed testimony before a Congressional committee investigating the legality of the use of armed drones for targeted assassination by US government personnel outside active battlefields. The doctors later diagnosed Tallis as suffering from an acute case of “adult mutism with occasional episodes of malignant catatonia.”

Cary and I have been visiting Tallis regularly now for years. We have not given up hope that he will someday recover—or at least that his psychological condition will improve sufficiently for him to be cared for at home. All three of us continue to practice his method. This enables all of us to refer during our visits to the “progress” each of us believes we are making. This gives us strength. This is also, I trust, a way of affirming to Tallis our continued belief in his underlying psychological health and the persistence of our trust in the acuteness of his historical vision.

As the professional editor in the family, I regularly remind both Tallis and Cary that I intend as some point to ask to see the record of their practice of Tallis’s method. They have tentatively agreed to this. My purpose, I explain, will be to compile a compendium of excerpts to demonstrate the method’s practical benefits—both to ourselves and perhaps to other would-be participants in Tallis’s eccentric but generative—even transformative—vision.

I have assured Tallis and Cary of their full editorial control over their individual entries. Nevertheless, I will urge them to keep their changes to a minimum. I want the excerpts that appear—as do those I have reproduced below—to bear the markings of only minor alteration while allowing their authors their prerogatives of review, revision, and final approval.

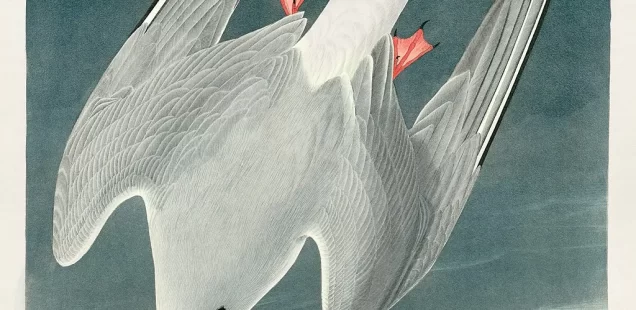

For reasons unnecessary to relate here, the title I plan to adopt for any more complete publication of Tallis’s method and the notebook entries written by the three of us that have resulted from it, will be taken, at Tallis’s request, from the title he intended for his last, uncompleted scholarly work, now abandoned. That title is John James Audubon Looks Up in Haiti.

Suffice it to say that that work concerned Tallis’s deep engagement with the early childhood of John James Audubon, born Jean Rabine (or Rabin). Audubon was an illegitimate white son, brought up until the age of six-and-a-half on one of his father’s (Jean Audubon) sugar plantations in Les Cayes, Saint-Domingue (Haiti after 1804). His mother died within eight months of his birth, and he was raised by his father’s mixed-race mistress and head of household, Catherine “Sanitte” Bouffard, and by his nine-years older half-sister, Marie-Madeleine.

In his last historical work, Tallis wanted to reconstruct a portrait of Audubon’s childhood from infancy to age six-and-a-half spanning the years 1785 to the outbreak of the Haitian Revolution on August 22, 1791. Tallis believed that the story of the publication between 1827 and 1838 of Audubon’s great work, The Birds of America, could not be accurately told or understood without a parallel history of the artist’s childhood. Only a narrative juxtaposition of these two periods of Audubon’s life could bring to light the meaning of the near total absence of the human figure from this great artist and naturalist’s almost beautiful American art.

Tallis once jokingly said to me that one confirmation of his thinking about Audubon was that the winning bid at auction for a complete set of Audubon’s original four-volume The Birds of America remains the second highest amount ever paid for a rare book ($9.65 million in 2018 or $11.48 million in today’s dollars). Only copies of Gutenberg’s Bible command higher prices.

Christopher:

January 27, 2024 (Saturday 4:38 AM)

Mariupol for a past, Kahn Younis for a present: the destruction of everyone in Rafah for a future: But first, all the historical dead will testify with the unanswerable persuasion of their perfected silence under a sparrow’s unbroken wing. Use these notes for a song, for a filler for the idea of historical justice—for a valuing of time as a duration and a weight of distance within an interval of sense. This for our living speech: “Complete destruction is the negation of peace.”

[Note: The words in quotation are reported to be those of President Dwight D. Eisenhower late in 1952 as President-elect upon being presented by his military nuclear war planning advisors with the destructive powers of the hydrogen bomb and the strategic necessity of the US adopting the policy of Mutually Assured Destruction against the Soviet Union; see Benjamín Labatut, Maniac (2023) 169.] (1.)

(These excerpts all use Tallis’s selections of quotations, chapter titles, and Audubon watercolor paintings to be memorized, recalled, and reflected upon by the practitioner of his method. Tallis always hoped that everyone will eventually adopt their own memorization template and musical tablature scheme once they become convinced of his method’s general utility for creating “meditative frameworks for inhabiting intervals of historical justice” from attending daily and in a disciplined way to one’s own mind’s spontaneous free associations.) (2.)

Memorization Template and Musical Note Tablature

[1. Note: 6. Language: “We shall try to show etc. . . .” (EL) ⇒ INTERVAL → Note 5. The State: “Thematization and conceptualization, which, moreover, are inseparable etc. . . .” (EL) ⇒ INTERVAL → Note 2. Immediacy: “Is not Nature, rightly read, that of which she is commonly thought to be the symbol merely. . . . We are in danger of forgetting that language which all things and events speak without metaphor” (HDT); 2. Chapter II: “As Soon as Thought Dries Up” (NM); 3. Bird 4: Arctic Tern (1833)]

[See The Birds of America, Plate 250. The engraving is made from a painting Audubon made on the deck of a ship off the coast of Labrador in late June of 1833. In Tallis Martinson’s method for historical meditation this image is to be contemplated in association with the following verbatim recollection by William Ingalls, a twenty-year-old medical student and member of the Labrador expedition who vividly recalled sixty years later the artist’s exact words (capturing in his transcription of them the sound of Audubon’s often noted by contemporary observers oddly French inflected and accented English). Audubon spoke to Ingalls as he was painting “from life” the bird he had shot the day before. Audubon, as he always did for the sake of accuracy and foreshortening, had pinned the bird’s body to the soft-pine board with wire nails. He had arranged the specimen to imitate the scene both he and Ingalls had witnessed the day before. In the cacophony of several men and boys shooting many birds out of the air, an arctic tern had fallen and was lying at Ingalls’s feet, confused and frightened but otherwise unharmed. Just then another bird, perhaps its mate, made a darting, vertical dive to within inches of the bird lying on the ground as if to inspect it or to try to give comfort or aid. Audubon had noted Ingalls’s strong reaction to the scene the day before remarking on it in his journal. When Ingalls approached Audubon the next evening on board ship as Audubon was painting the scene of the vertically diving bird they had witnessed together, Ingalls reports, “I darkened the little table at which Mr. Audubon sat. He looked up and saluted me with ‘Hello, Sangrido’ [‘Sangrido’ can mean ‘bleeding’ in Spanish] (he gave me this name the first day), ‘He is here, he is scared, affrighted, he is looking up at you, you cannot help him.’”] (3.)

Tallis:

Wednesday, January 31, 2024

“It is every individual’s obligation. . . .”

[1. Note 8 (Octave). Lucidity: “Everyone will readily agree etc. . . . Peace is produced as this aptitude for speech. The eschatological breaks with the totality of wars and empires in which one does not speak. The first vision of eschatology (hereby distinguished from the revealed opinions of positive religion) reveals the very possibility of eschatology, that is the breach of the totality, the possibility of signification without a context. The experience of morality does not proceed from this vision, it consummates this vision. Ethics is an optics. But it is vision without image, bereft of the synoptic totalizing and objectifying virtues of vision, a relation or intentionality of a wholly different type etc. . . .” (EL) ⇒ INTERVAL → Note 1. Labor: “Labor is the living, form-giving fire. It is the transitoriness of things, their temporality as their formation by living time” (Karl Marx, Winter of 1857-58) ⇒ INTERVAL → Note 5. The State: “Thematization and conceptualization, which moreover are inseparable, are not peace with the Other but the suppression or the possession of the Other. Possession affirms the other but in the context of the negation of his [their] independence. ‘I think’ comes down to ‘I can,’ —to an appropriation of what is, to an exploitation of reality. Ontology as first philosophy is a philosophy of power. It issues in the State and in the nonviolence of the totality without securing itself against the violence from which this non-violence lives and which appears as the tyranny of the State. The truth, which is supposed to reconcile persons, here exists anonymously. The universal presents itself as impersonal, and this is another inhumanity” (EL) 2. Chapter III. “The Idea of Universal Equality is a Historical Accomplishment”; 3. Bird 2. “Wood Thrush” (1822)]

Cary:

January 31, 2024

You’d have to say it as many times as there are rules for the arrangement of all these stones ever to have the chance to go home again. A forest of New World winters: a forest of blackest, deepest green. Yesterday I saw a small and graceful hawk—it might have been a male “sharp-shinned hawk” now that I have looked it up—alight softly at the very top of the tallest spruce tree. There was not another like it anywhere near. The gentleness of the bird’s motion seemed to me to be the deepest anyone or anything could feel. Nothing existed between the intervals of the easy patience of the gracefulness of its predator’s unhurried, unforced intention—a perfectible model for the temporality of some approaching deep state’s unhesitating gentleness of pleasured, non-consenting force. Today the man said (surely he must have read it aloud to someone else)—at least he wrote this down and that is the version that has come down to us: “Marx for a soul”—I told my father that for purposes of memorization he had to complete the sentence fragment from the Judge’s Order of Dismissal and his denial of the plaintiffs motion for preliminary injunction. I asked him to change his entry to read:

“It is every individual’s obligation to confront the current siege in Gaza, but it is also the Court’s obligation to remain within the metes and bounds of its jurisdictional scope.” (From Judge Jeffrey S. White’s Court Order, January 31, 2024.)

We must teach ourselves to speak again from here.

[1.Note 4. Justice: “To affirm the priority of Being over Existents etc. . .” (EL) ⇒ INTERVAL → Note 5. The State: “Thematization and conceptualization, which, moreover, are inseparable, are not peace with the other but the suppression or possession of the Other. Possession affirms the other but in the context of the negation of his independence. ‘I think’ comes down to ‘I can,’ to an appropriation of what is, to an exploitation of reality etc….” (EL) ⇒ INTERVAL → Note 6. Language: “We shall try to show etc….The same is essentially identification within the diverse or history or system. It is not I who resist the system as Kierkegaard thought, it is the Other” (EL); 2. Chapter I: “The Complicity of Presence”; 3. Bird 1. “The Great Egret,” a painting by John James Audubon (perhaps his greatest) executed together with his fourteen-year-old prodigy apprentice, Joseph Mason, in New Orleans in the fall of 1821, not used for the engraving depicting the species in Audubon’s The Birds of America (1827-1838)]

Addition to today’s meditation following the interior recitation of the applicable memorized passages: “An impunity of detonated bad faith no infant in Palestine was ever intended to survive (some speech for it): Marx for a soul; Palestine for a home; dispossession for a friend.”

Christopher:

February 1, 2024

Some speech for when the state fails and must fall away. Must people fail when institutions do? Here is speech. Let us do more with it—and do justice in it to each other—the violence of force cannot be made into its own justifying argument. When a state—or any speaker for the state—affirms this constitutive structure of impunity and we obey it, we break the coherence of any continuity it is worth the wait or art to die for. Some other word, some other act, some other principle than the poisoned bad faith the state ushers in when it declares its perfected justice inaccessible—when it stoops before the killers it has legally found accountable for genocide not to prevent or punish but to implore: “There are rare cases in which the preferred outcome is inaccessible to the Court. This is one of those cases. The Court is bound by precedent and the division of our coordinate branches of government to abstain from exercising jurisdiction in this matter. Yet, as the ICJ has found, it is plausible that Israel’s conduct amounts to genocide. This Court implores Defendants to examine the results of their unflagging support of the military siege against the Palestinians in Gaza.” (From Judge Jeffrey S. White’s grant of dismissal and denial of motion for preliminary injunction in Defense for Children International-Palestine, et. al., v. Joseph P. Biden, et. al., January 31, 2024)

These words for it: Marx for a soul; Palestine for a home; dispossession for a friend. The lecturer at the podium is saying, “Coherence as narrated frames of continuity within modernity is a vital state interest.”

Memorization Template and Musical Tablature

Ad libitum:

Endnotes.

1 The full Eisenhower quotation reads: “There is no need for us to build enough destructive power to destroy everything. Complete destruction is the negation of peace.”

2 An Appendix is attached to this presentation of excerpts from the practice of Tallis’s method listing the texts and art works from which Tallis has constructed his own personal memorization template and musical note tablature.

3 Christopher has learned to practice Tallis’s method by meditatively performing the following steps: first he attends calmly to the free-floating associations that cross his mind until he is struck by a particular phrase or word group that comes spontaneously into consciousness. He then writes that fragment of thought down without any anxious immediate straining to decipher any of its larger meanings. From there he jots down whatever verbalizations of thought come next. In this entry of January 27, this process has produced: “Mariupol for a past, Kahn Younis for a present: the destruction of everyone etc. . . .” ending with “’Complete destruction is the negation of peace.’”

Instead of letting these word fragments derived from the interplay of partial thoughts evaporate into the abyss of memoryless forgetting, Tallis attempts to hold on to them by writing them down and then proceeding meditatively to align them with his template of valued prior memorizations. He loosely matches his free association’s succession of words and phrases to a quick inventory of his musical scale’s eight memorized texts, then places the musical phrase he intuitively constructs from three of these “notes” within one of his template’s four possible chapters, and then finally juxtaposes that musical phrase with his mind’s image of one of four of Audubon’s original watercolors of American birds.

The value of doing all this, Christopher senses, is the creation of a discipline with which to inhabit durations of thought freed momentarily from immediate ideological pressures. Such a discipline, derived from his own mind’s free associations, he hopes, will teach him to experience himself as a potential participant in a conceivably just historical narrative of universal peace. He experiences the three note musical phrases his meditations silently produce as potentially creating a duration of freedom—as in the direction within a written musical score given by a composer to the performer to play a particular passage: ad libitum. At one point in his notebooks, Tallis calls these attempts to inhabit the meditative intervals between the prompted internal recitations of his memorized texts “a civic reach for lived durations of justice in the midst of the seamless coercions of our empire’s forever wars.”

Appendix.

Schematic Summary of Tallis Martinson’s Memorization Template and Musical Tablature

Memorized Notes of Tallis Martinson’s Meditative Method’s Diatonic Musical Scale

- Note 1. Labor: “Labor is the living, form-giving fire. It is the transitoriness of things, their temporality as their formation by living time.” Karl Marx, 1857-58 (21 words)

- Note 2. Immediacy: “Is not Nature, rightly read, that of which it is commonly thought to be the symbol merely. . . . We are in danger of forgetting that language which all things and events speak without metaphor.” Henry David Thoreau, 1849, 1854 (35 words)

- Note 3. Possession: “Possession is preeminently that form by which the Other becomes the same by becoming mine.” Emmanuel Levinas, 1961, 46 (15 words)

- Note 4. Justice: “To affirm the priority of Being over existents is to already decide the essence of philosophy; it is to subordinate the relation with someone, who is an existent (the ethical relation), to a relation with the Being of existents, which, impersonal, permits the apprehension, the domination of existents (a relationship of knowing), subordinates justice to freedom.” Emmanuel Levinas, 1961, 45 (56 words)

- Note 5. The State: From: “Thematization and Conceptualization, which moreover are inseparable, are not peace with the Other but the suppression or possession of the Other” to: “Truth, which should reconcile persons, here exists anonymously. The universal presents itself as impersonal, and this is another inhumanity.” Emmanuel Levinas, 1961, 46 (109 words)

- Note 6. Language: From: “We shall try to show the relation between the same and other—upon which we seem to impose such extreme constraints—is language” to: “But to say that the other can remain completely other, that he enters only into the relation of conversation, is to say that history itself, an identification of the same, cannot claim to totalize the same and other. The absolutely other, whose alterity is overcome in the philosophy of immanence on the allegedly common plane of history, maintains his transcendence in the midst of history. The same is essentially identification within the diverse, or history, or system. It is not I who resist the system, as Kierkegaard thought; it is the other.” Emmanuel Levinas, 1961, 39-40 (581 words)

- Note 7. Desire: From: “Desire is absolute if. . . .” to: “It is this perpetual postponing of the hour of treason. . . that implies the disinterestedness of goodness, the desire for the absolutely other or nobility, the dimension of metaphysics.” Emmanuel Levinas, 1961, 34-35 (363 words)

- Note 8 (Octave). Lucidity: From: “Everyone will readily agree it is of the highest importance to know whether we are not duped by morality. Does not lucidity, the openness of the mind upon the true, consist in catching sight of the permanent possibility of war” to: “Peace is produced as this aptitude for speech. . . . [E]thics is an optics but it is a ‘vision’ without image, a relation or intentionality of a wholly different type—” Emmanuel Levinas, 1961, 21-23 (1202 words)

Chapter Titles for Tallis Martinson’s Method’s Memorization Template.

Chapter I. “The Complicity of Presence”

Chapter II. “As Soon as Thought Dries Up” (Nadezhda Mandelstam)

(The title of Chapter II is taken from Nadezhda Mandelstam’s Hope Abandoned, 1974, 10. Mandelstam writes, “As soon as thought dries up, it is replaced with words. A word is too easily transformed from a meaningful sign into a mere signal, and a group of words into an empty formula, bereft even of the sense such things have in magic. We begin to exchange set phrases not noticing that all living meaning has gone from them. Poor trembling creatures—we don’t know what meaning is; it has vanished from the world. Meaning will be restored to us when we come to our senses and recall that we are responsible for everything.”)

Chapter III. “Universal Equality is a Historical Accomplishment”

Chapter IV. “The State is a Necessary but Insufficient Instrument of Historical Justice”

Selected Plates from The Birds of America

Four of More than 435 Original Watercolor Paintings by John James Audubon Used for Engraving the Plates for The Birds of America (1827-1838)

- “The Great Egret” (1821) (Not used for The Birds of America)

- “Wood Thrush” (1822)

- “Golden Eagle” (1835)

- Arctic Tern” (1833)

Textual Sources for Tallis Martinson’s Memorization Template and Musical Note Tablature.

Karl Marx (writing in 1857-58), see Grundrisse: Foundations of the Critique of Political Economy (Rough Draft), Translated with a Foreword by Martin Nicolaus (Penguin Books in association with New Left Review, 1973). (Sometimes noted in Tallis’s Memorization Template as: (KM).)

Henry David Thoreau (writing in 1849 and 1854), see A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers and Walden; or, Life in the Woods. (HDT)

Emmanuel Levinas, Totality and Infinity: An Essay on Exteriority (1961). (EL)

Nadezhda Mandelstam, Hope Abandoned (1974). (NM)

John James Audubon, The Birds of America (1827-38). (JJA)

John James Audubon, Writings and Drawings, edited by Christoph Irmscher, Library of America (1999).

Alexandra Mazzitelli, Marjorie Shelley, and Roberta J. M. Olson, Audubon’s Aviary: The Original Watercolors for The Birds of America (2012).

Richard Rhodes, John James Audubon: The Making of an American (2004).

Charles Rosen, The Classical Style: Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven (1971).