PATRICK LAWRENCE: The Dialectic of the Draft

Americans will understand themselves less fantastically if they consider the extent to which the end of the Selective Service System a half century ago gave them permission to put their public selves to sleep.

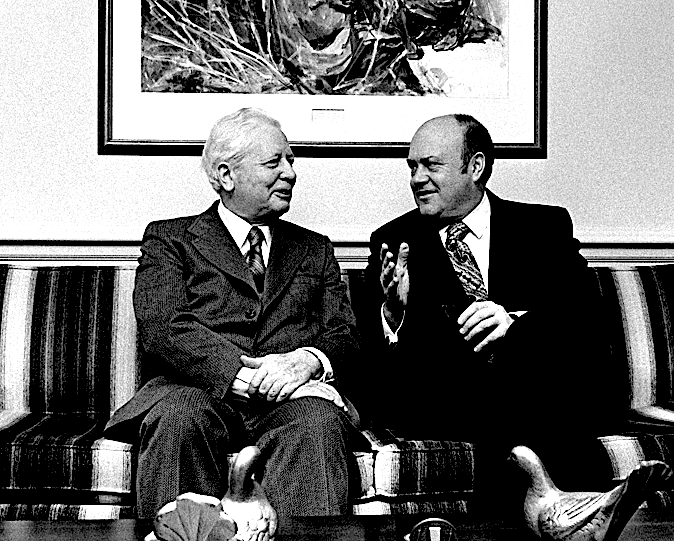

It is 50 years ago now that old Melvin Laird, President Richard Nixon’s defense secretary and the architect of “Vietnamization” in the Indochina war, ended America’s military draft.

Henry Kissinger — with whom Laird was famously at odds, but that is another story — had just finished negotiating the Paris Peace Accords with LêDúc Tho, veteran of French “tiger cages” and Hanoi’s chief diplomat at the talks.

Tho, a tough-minded revolutionary the whole of his life, refused the Nobel Peace Prize when the committee in Oslo proposed later in 1973 that he share it with Nixon’s secretary of state — a principled move, given there was no peace for two more years.

But Laird, eager to assuage the explosive antiwar movement at home, pounced. When he suspended the Selective Service System’s conscription program on Jan. 27, 1973 — the same day Kissinger signed the accords in Paris — it was nearly half a year ahead of his announced schedule for Vietnamization, which he had initially named “de–Americanization.”

Now we read in Military.com, which puts itself across as “a resource website for military members, veterans and their families,” that Congress must reconstitute the conscription system to counter a drastic shortage of personnel in the armed services. “We need a limited military draft” is the head atop the July 29 piece, which reports:

“Today, the military needs only about 160,000 youth from an eligible population of 30 million to meet its recruitment needs. But after two decades of war — both of which [sic] ended unsuccessfully — and low unemployment, many experts believe the all-volunteer force has reached a breaking point. And American confidence in its military is at a low.”

It turns out that reviving the draft is something of a running theme at Military.com. On Sunday it published another piece asserting that the American military cannot find enough people to put in uniform and in harm’s way. It turns out there is a here-and-there debate on the question of the draft in our midst.

[Related: US Vets Try to Stop Students from Joining Up]

I credit the estimable Dave deCamp for bringing this matter to my attention in a piece he published last week on Antiwar.com. I have since read up on all this talk. Most of those commenting seem to think there is little chance that the Selective Service System will be put back in action.

Congress would have to authorize it, so bringing back the draft divides in two: It is a practical question — the Pentagon needs more soldiers and sailors — and a political question. Politics in our wayward republic, if you have not noticed, almost always trumps good sense, bad sense, and everything in between.

I am moved to pose a question I have considered for a very long time. It is a bitter question. For a long time I have been chary of posing it anywhere more public than the dinner table. This could come across very badly. But here goes.

Considering the Consequences

On the face of it there would seem no defending a state’s practice of forcing some of its citizens to carry arms, go to war and kill people. Inarguably, this is all the more so when the state in question is running a violent empire. But was the Nixon administration’s very effective, very consequential move to drop the draft a good thing or a bad thing?

This is the question. However one may come down on it, my case is that it’s time to consider it. We will better know ourselves as we do.

How well I recall those times late in the Vietnam era. I will relate a little of them in the cause of answering this question. Preview: In my view, America’s switch from a citizen’s army to a paid, “voluntary” army served in important respects to open the door to a festival of public irresponsibility as to the conduct of the foreign and military policies executed in Americans’ names and by means of Americans’ tax dollars.

In November 1969, with the largest antiwar demonstrations in U.S. history a few days in the past, the Nixon administration announced that it would begin running the draft by lottery. This, a first step toward a voluntary army, was conducted according to birthdays. The lottery was drawn, like some kind of macabre game show, on Dec. 1.

I was a student in Paris at the time and had a draft card (2–S student deferment) in my wallet. My mother back in the States was nearly beside herself as the day of the lottery approached. Strange as it may sound, I took no interest whatsoever in the lottery. There was simply no question of putting on a uniform, going through basic, and shipping out to Southeast Asia. As fortune would have it, I would simply have stayed in France.

I never had to test my convictions. My lottery number was 329 — well, well beyond the number the Selective Service would ever reach. As I recall it, anyone who drew a number north of 250 or so simply forgot about the draft, home free. Four years later, everyone did and everyone was.

At the time, the end of the draft was universally understood as a massively good thing. It was taken in part as a triumph for the antiwar movement, and fair enough. Power, as in Washington’s power, was spooked by the extent of the movement’s strength, coherence and determination.

It took some years after Saigon’s rise in 1975 to wonder about the consequences of the end of the draft and the new dependence Americans shared on an army of volunteers. They were inevitably drawn from poor and working-class communities and were in it, in many, if not most cases, because they couldn’t otherwise find good work.

Then Came the Meddling

Then came the meddling, the covert ops, the proxies, the bombings, the coups, the what have you, running from Zaire, to Angola, to Iran, to Libya (multiply), to Grenada, to Nicaragua, to Panama, to the big “etc.” Anyone recall Operation Praying Mantis, in 1988, when the Pentagon attacked and more or less destroyed the Iranian Navy? I didn’t think so: It’s a trivia question now.

The Persian Gulf in 1990, Afghanistan in 2001, Iraq in 2003, Libya yet again, Syria. I won’t ask where the voices of protest were because there were some. Groups such as Veterans for Peace, founded in 1985 with a multigenerational membership, remind one of the old VVAW of the Vietnam war era.

Setting aside such honorable gatherings, is there any question of the apathy, the coarse indifference, the willful somnambulance abroad in the republic as the imperium proceeds with its imperial business? By the time we get to Ukraine, we find the people whose intellectual forbears stood at barricades instead cheering a proxy war and pretending, per the propaganda, that it was “unprovoked.”

There are numerous explanations for this shift in consciousness — psychological, social, political, even economic. The bitter truth is that we have to include among these explanations the fact that Americans are no longer held responsible for waging wars. They pay others to wage them.

Laird and Nixon had it right, to put the point another way: Take them out of the line of fire, their lives never on the line, and they will go to sleep, ceasing to give a damn. Rome may be burning, the U.S. having set afire many Romes, but let us stay with Barbie and Taylor Swift (I think I can tell the difference).

Collective Irresponsibility

You have the shadow-boxers, as always — escapists in their own right. Last Wednesday Newsweek published the results of a July 25–26 poll conducted by Redfield & Wilton, showing that nearly half of those aged 18 to 42 — I am combining so-called Gen–X and Gen–Z respondents — said they supported or strongly supported sending U.S. troops into combat in Ukraine. Nearly a third of those older than 59 concurred.

These people watch too many Tom Cruise movies and are merely an upside-down measure of U.S. collective irresponsibility.

Considering those in these age brackets would conceivably be eligible for service, or be the parents of the same, the poll would be far more interesting were it conducted after these chest-out people were told they had call-up letters coming their way. I will not guess as to the hypothetical result, except to say the numbers would most definitely be other than what Redfield and Wilton registered.

The recent death of Daniel Ellsberg gave me (and I am sure others) cause to consider again the case of Randy Kehler. Kehler was an inspiration to Ellsberg in the course of his “awakening,” as Ellsberg put it. Kehler turned in his draft card, went to prison, and continues to live as we speak a life of principled activism. We must never complain of our struggles and responsibilities, I conclude when I think of such people. It is our struggles and responsibilities that make us.

No, I am not arguing for a reconstitution of the draft, should this not already be clear. I am tempted — and no more at this point — merely to conclude, that were the draft to be reconstituted, it would do a lot of Americans a lot of good by forcing them to shut off the televisions, put away the Frisbees, stop daydreaming of high deeds on battlefields they will never see, think seriously of what their country is doing in their names, and then assume responsibility for it.

There is a dialectic attaching to the question of the draft and the obligation or not to “serve one’s country,” as the saying goes. This is another way to state the case. Americans will understand themselves more authentically, less fantastically, if they consider the extent to which the end of the Selective Service System a half century ago gave them permission to put their public selves to sleep. A decade later we were well into “the me decade,” weren’t we?

I spent a brief time in Switzerland this past spring, and some of what I saw bears upon these thoughts. As it has long been, every Swiss, from 18 to old age, serves in the army, a uniform and a rifle in the closet. For women, service is voluntary, and there are the American equivalent of “CO” exemptions. Ten years ago, there was an initiative — the Swiss, having a direct democracy, love their initiatives — proposing to abolish conscription. Three-quarters of the country voted it down.

How shall we think of this?

It comes down to the presence or absence of an idea worth defending, in my view, and I am avoiding “nationalism,” for that is not the point. “Switzerland” is the idea: what it is as a community, as a polity, what it means to be Swiss, the obligations, what one owes the community called “Switzerland” by virtue of belonging to it. “Armed neutrality,” the principle governing their relations with others, is part of this, a big part, and it is in defense of it the Swiss keep rifles in their homes.

A thoughtful reader, I should add, wrote to me after I returned from Zurich and mentioned my sojourn in a column, “Yes, I’ve been to Switzerland a few times. I always tell myself, ‘This is what peace looks like.’”

Indeed. And after the profound divisions among Americans during the draft, now our purported leaders’ resort to an army of the deprived: Is this what war looks like?

It is one way to put it, I would say. As the 19th century turned into the 20th, Mark Twain, William Jennings Bryan, and all those early anti-imperialists understood America had a choice: It would be empire abroad or democracy at home, but it could not be both. The choice is now bitterly obvious.

This leaves Americans with nothing left to believe in, nothing worth lifting a finger or even raising a voice to defend. As our militarists mull whether to reinstitute the draft to fill the ranks of the reluctant, we should consider: This is what empire looks like.

If conscription truly motivated citizens to become more involved with policy and war making, then the Vietnam Holocaust would not have occurred. Switzerland is a poor analogy, as it has never been an aggressor nation which its citizens must rally to prevent from oppressing other nations and peoples. Conscription made the invasion and occupation and the mass killing of people possible in Vietnam, and, originally, with support of a significant proportion of America’s subjects. If the US had had conscription in 2003, Americans would have supported the invasion of Iraq and the invasion of Iran. Conscription makes it easier to wage war through the popular rallying of supporting the troops. No peace advocacy in America is sufficient to counter that ‘argument.’ At least not until 25,000 or more Americans die.