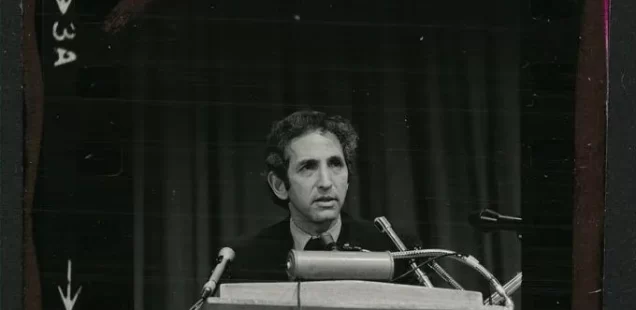

Patrick Lawrence: Ellsberg and ‘The Process of My Awakening’

Of all the fine things written and said about Daniel Ellsberg since his death June 16, there is a thread running through them we ought not miss, a story Ellsberg himself told better than anyone else. It is a story from which we can all learn. As we consider this story, we can embrace Ellsberg as an exemplar as much as he was a courageous man of conscience. As he put it in an interview some years ago, “courage is contagious.”

Ellsberg did not give the story I have in mind a name, a title, a headline, or any such designation, but he may as well have, and I take the liberty of drawing from his words to name it now, the process of Dan Ellsberg’s awakening.

In 1970, a year and maybe less before Ellsberg gave the Pentagon Papers to the New York Times, The Washington Post and The Boston Globe, he traveled to Nevada City, California, a small burg 150 miles north of and inland from San Francisco, and knocked on the door of the house wherein dwelt Gary Snyder, one of the brightest lights among the Beat poets. We can confidently infer that Ellsberg had the still-secret Pentagon Papers in his car, as he wrote the following in “The First Two Times We Met,” an essay that appeared in a collective celebration of Snyder’s life and work called Dimensions of a Life (Sierra Club Books, 1991):

I didn’t show him any papers from the trunk, so as not to implicate him; but I hinted that he was implicated anyway, in the process of my awakening. I wanted to thank him.

Let us consider the scene. How far did Ellsberg drive that day to knock unannounced on a noted poet’s door simply to say thank you? Thank you for what? What had Snyder done, and when, that was worthy of such gratitude?

As Ellsberg told the story on various occasions, he had met Snyder in Kyoto in 1960—the first of the two times mentioned in his essay. Snyder was then halfway through a decade-long study of Zen Buddhism under the tutelage of Oda Sesso Roshi. Ellsberg was living in Tokyo at the time, developing policies concerning the use of nuclear weapons for the Office of Naval Research. As Ellsberg recounted the meeting, the two met by chance at a bar near Ryoanji, the Zen monastery famous for its garden. He had by then read of it in The Dharma Bums, the Kerouac novel, and, so inspired, had traveled to Kyoto more or less as a tourist.

Imagine reading Kerouac, training to a place he writes of, and there meeting one of the novelist’s close friends. In the accounts I have read, the Vietnam War was a major topic of conversation. Ellsberg was still a dedicated supporter; Snyder, who by this time had the sturdy composure of the monks under whom he studied, talked of it from the other side. They liked one another, a little improbably from our perspective. They had lunch together the next day, continuing the conversation begun the previous evening.

A decade later Ellsberg identified the encounter with Snyder with his “awakening.” And so the defense technocrat drove a long way, we have to assume, to thank the poet. There is something in this to love.

Nine years after the Kyoto meeting and a year before the Nevada City reunion—we are now in August 1969—Ellsberg attended a gathering sponsored by the War Resisters’ League. (The good old WRL.) This was at Haverford College. You have to figure Ellsberg was by this time at some stage in the process of his awakening: Why would he be there otherwise? Among the speakers that evening was an antiwar activist named Randy Kehler, who was then on his way to prison, without so much as a flinch, for turning in his draft card and refusing all cooperation with the Selective Service System.

Parenthetically, Kehler had his life hanging on the line long after serving his prison term, which ran most of two years. After he long refused to pay taxes to protest the Pentagon’s budget, in 1989 the federal government seized the Kehlers’ house in Colrain, a small town in northern Massachusetts. It was Chris Appy, the UMass historian of the Vietnam War, who related this story to me many years after the fact.

That evening at Haverford had much to do with Ellsberg’s subsequent decision to copy the Pentagon Papers and, two years later, do with them what we all know he did. Ellsberg recounted his experience to Marlo Thomas many years later. “I left the auditorium and found a deserted men’s room,” he told the actress and sometime activist. “I sat on the floor and cried for over an hour, just sobbing. The only time in my life I’ve reacted to something like that.”

Let us ask at this point who was crying on the men’s room floor at Haverford, that we can understand the moment for what it was. Was it the eager Marine Ellsberg had been, the RAND war planner, the technocrat who toured the carnage in Vietnam, the Defense Department analyst? Or was it the person Ellsberg had just then become, mourning all that he had been and all that he had done until that moment—the Marine and the analyst having that very evening died?

Ellsberg’s account of that evening brings to mind Saul on his way to Damascus as related in Acts 9. There was a fall in each case and then an epiphany, a sudden conversion. Everything thereupon changed in each case. Saul became Paul, and, whatever you may think of him, St. Paul altered the course of Western civilization. Ellsberg, perfectly fair to say, spent the rest of his life attempting to do the same.

I go back now to something Ellsberg said in that brief essay he contributed to the book Gary Snyder’s friends put together to honor him. What most affected him when he first met the poet was what he intuited: He saw someone “who was in charge of his own life, a model of the way a life could be lived.” This comment is key, it seems to me. It explains why Ellsberg made the long drive to Nevada City a decade later. And it tells us what later happened to Ellsberg in the fullest sense. When we think of Ellsberg’s presence in the public sphere, we conclude that getting the Pentagon Papers published was the most important thing he ever did. But he could never have done that, we must not miss, if he had not first done something far larger: If he had not changed his life—the way he lived it and what he did with it.

If he had not, in other words, completed the awakening, his chance encounter with a Beat poet did much to set in motion. This, “the process of my awakening,” is the very truest story Ellsberg has to tell us and the one from which we can learn the most.

As in St. Paul’s story, coming awake was the wellspring from which flowed everything Ellsberg did after, figuratively speaking, he fell from his horse on the road to his Damascus. It was his awakening—in essence to the difference between truths and lies—that enabled him to consider the prospect of life in prison with a remarkable aplomb, even equanimity. He knew, by the time he faced that prospect, that there was no turning back. You don’t get to go back to sleep once you come awake. Aeschylus famously put it this way:

He who learns must suffer. And even in our sleep, pain that cannot forget falls drop by drop upon the heart, and in our own despair, against our will, comes wisdom to us by the awful grace of God.

Ellsberg understood this, surely. He was well aware that to come awake means to suffer and of his own need to be pulled along by others as he made his way toward the state of wakefulness. From a 2006 interview:

I’d like peoples’ consciences to be rethought and reshaped as much as possible … Learning from people who have already had that conversion is very helpful. In my case it was crucial for me to meet people who were of that mind and who were going to prison rather than take part at all in what they saw as a wrongful war. … Courage is contagious, and coming into contact or exposing yourself to people who are taking those risks is very helpful as a first step toward doing it yourself.

“As a first step toward doing it yourself.” Brilliant. It is what Ellsberg had most to offer us, what we can learn from him and put most directly to use in our own lives. Ellsberg’s story, the one he told in recounting the incidents noted here—Kyoto, Nevada City, Haverford—is in part one of surrender. He had to give up the eager Marine and the accomplished war planner. This meant giving up altogether a worldview. It left him weeping on a men’s room floor.

But his story is also one of embrace, of transcendence, of self-mastery, of living “a life that could be lived.”

Ellsberg’s first wakeful act was to rip the veil from the pointless savagery of our Vietnam adventure. Few of us will ever have occasion to do anything of remotely comparable magnitude. But each of us, providing we each summon the courage, can act as truly, as faithfully, as loyally to the human cause as Ellsberg did. No illusions here: Most of us prefer the irresponsibility of slumber. But for those who so choose, we can allow ourselves to awaken. We can accept the burdens knowledge always brings with it, just as Dan Ellsberg showed us in his own life.