Patrick Lawrence: Why Can’t Blinken and Sullivan Get China Right?

The Biden admin’s continuation of Trump-era policies with China have not boded well thus far.

It is two years now since Antony “Guardrails” Blinken and Jake Sullivan flew to Anchorage and in a matter of two days made a perfect mess of the Biden administration’s relations with China. For Joe Biden’s secretary of state and national security adviser, this was their first major outing since the new president took office two months earlier, and their first encounter with senior foreign policy people from China. A big, defining deal. And a big, defining disaster.

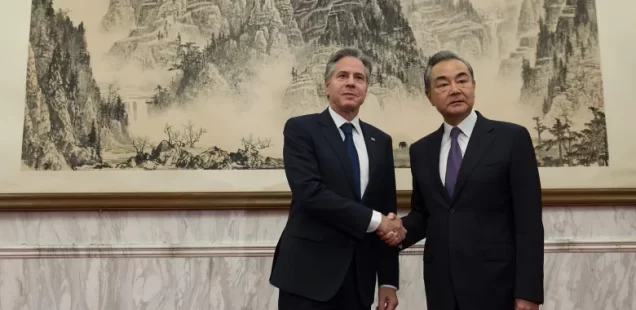

Guardrails and his not notably imaginative sidekick are now embarked on their latest effort, of many, to repair the damage they have done. Biden’s top diplomat finished two days’ talks in Beijing Monday, which ended with a 35–minute encounter with President Xi Jinping. Sullivan is now pushing a strategy so grand some of us are calling it “the Sullivan Doctrine.” If I may I’d like to type that phrase again for the sheer kick of it: The Sullivan Doctrine. Now there’s a thing.

It would be a great mistake to expect anything of either of these efforts. In the most important relationship the U.S. will have to manage in this century, Washington can do nothing more than repeat positions Beijing has already made clear are unacceptable. The only alternative—Blinken’s choice this week—is to say nothing and count it a success that another mess has been averted. The bitter truth is that Joe Biden’s best and brightest are too paralyzed by the ideology of American primacy to come up with a single, solitary new thought as to how to address other great powers as we enter an historically new era.

Blinken used to meet Chinese counterparts with the professed intention of “easing tensions” or building his famous guardrails so that when the U.S. provokes and provokes and provokes the Chinese they understand that we are for peace and freedom and things need not get too far out of hand. This time getting the invitation to Beijing and getting someone to talk to him when he arrived seem to have been the limits of our top diplomat’s aspirations.

Blinken got his invitation and he got the Chinese to talk to him again after many months when they declined to do so. On Sunday he convened with Qin Gang, the recently named foreign minister, who opened with the observation that the Sino–U.S. relationship “is at its lowest point since its establishment”—an unsubtle whack at the man who led the way down the cellar stairs. For the rest of their talks Qin and Blinken agreed … to talk. Peruse the Foreign Ministry’s readout. Pure saccharine.

Xi did not let Blinken know he would receive the American secretary until an hour beforehand. To put this bit of protocol in context, Xi recently spent several days with French President Emmanuel Macron; Luiz Ignácio Lula da Silva, the Brazilian leader, had lengthy meetings with Xi during a five-day visit last month. This is how the Chinese conduct diplomacy after a couple of millennia at it: Language is but one medium, gesture another. The take-home here will be obvious.

Blinken’s 35–minute exchange with Xi was nearly as short on substance as his talks with FM Qin the previous day. But not quite. Nothing of import, or even anything of no import, got done. But Xi’s sweepy, generalized remarks had a clear position buried in them. From the Chinese readout:

Planet Earth is big enough to accommodate the respective development and common prosperity of China and the United States. The Chinese, like the Americans, are dignified, confident and self-reliant people. They both have the right to pursue a better life. The common interests of the two countries should be valued, and their respective success is an opportunity instead of a threat to each other.

And:

The two countries should act with a sense of responsibility for history, for the people and for the world, and handle China-U.S. relations properly. In this way, they may contribute to global peace and development, and help make the world, which is changing and turbulent, more stable, certain and constructive.

And:

President Xi stressed that major-country competition does not represent the trend of the times, still less can it solve America’s own problems or the challenges facing the world. China respects U.S. interests and does not seek to challenge or displace the United States. In the same vein, the United States needs to respect China and must not hurt China’s legitimate rights and interests. Neither side should try to shape the other side by its own will, still less deprive the other side of its legitimate right to development.

My plain-English interpretation: I have not been in any great hurry to meet you, Mr. Blinken, but so long as you are here, China expects to be addressed as an equal, you ought to pay more attention to our legitimate rights as a sovereign nation, your controls on technology exports are intentionally damaging to our development, and you should stop swanning around the world telling others how to live.

Xi’s sendoff, as quoted in The New York Times’s Monday editions, requires no paraphrasing. “State-to-state interactions should always be based on mutual respect and sincerity,” Xi said. “I hope that through this visit, Mr. Secretary, you will make more positive contributions to stabilizing Sino–U.S. relations.”

Well, Antony Blinken got the Chinese to talk to him. But getting people who do not trust you to talk to you is not a policy. If you count it an accomplishment, you have set a very low bar. In my read, what Blinken got back from the Chinese was subtly conveyed indifference to his presence, as if they received him as a courtesy only after months of pestering, and a few reminders that, while they would like to step beyond hostile relations, they have no intention of flinching in the face of American hostility.

“We both agree on the need to stabilize the relationship,” the BBC quoted Blinken as telling reporters after his talks Monday afternoon Beijing time. But he was quick to note “the many issues on which we profoundly—even vehemently—disagree.”

This is a hell of a thing for Guardrails to say under the circumstances. I take from this remark and his apparent failure to respond to the Chinese side’s general points, that Blinken flew home Monday evening with the same two problems he had with him on his arrival in Beijing over the weekend. One, there is no new sign the Chinese trust the regime Blinken represents to say one thing and do the same thing, rather than say one thing and do another, which has been the practice among Biden’s diplomats and national security people since Blinken and Sullivan passed those fateful days in Anchorage two years ago this spring.

Two, even if Blinken had more imagination, initiative, and diplomatic skill than he manifests, he has very little available to him to offer the Chinese by way of repairing the damage in ties for which the U.S. is responsible. Any substantive recognition of the Chinese position on questions such as Taiwan, semiconductor chips, security in the South China Sea, or anything else of importance would provoke shrill ire on Capitol Hill, where a perverse bipartisan consensus rules. By Monday afternoon there were already voices raised in objection to Blinken’s straightforward and at this point still true statement, “We do not support Taiwan independence.”

Antony Blinken finally got to look like a diplomat in Beijing. Now where were we?

■

For his part, Jake Sullivan gave a significant speech—well, it was supposed to be significant—at the Brookings Institution at the end of April. He called it “Renewing American Economic Leadership”—so, a problem before he even began—and in it called for “a different brand of U.S. diplomacy,” which is another problem: Sullivan advocates no such thing. His schtick is by now familiar to those who follow him. Our policy until now has been that 4 and 3 make 7, he will say, but it’s different now: 5 and 2 make 7. And we’re weighing a dramatic policy shift such that we’ll soon announce that 6 and 1 make 7.

It seems the best Sullivan can do, given the severe limitations his dedication to neoliberal ideology impose on his intellect. After voters sent Hillary Clinton packing in 2016 and he was for a time out of work, Sullivan wrote a long essay for The Atlantic making the argument that America had to “rescue and reclaim” its exceptionalism so that it can lead the world again despite all the suffering and destruction our claim to exceptionalism was by then causing around the world. It is blood-from-a-stone with this guy, you see. During the 2020 campaign season Biden once called Sullivan “a once-in-a-generation mind.” The thought has long fascinated me. It is hard to single out the most preposterous nonsense our president has tried to sell Americans, but this is a contender in my reckoning.

When Biden came to office, Antony Blinken and Jake Sullivan were supposed to reverse some of the extravagant damage the fanatical Mike Pompeo wreaked as Donald Trump’s secretary of state—the reckless escalation of tensions in the Taiwan Strait and the South China Sea, the Draconian trade tariffs and sanctions, the escalation of the U.S. military presence in the region, the constant harping on the Chinese Communist Party as the source of all earthly evil in our time. Let us bring some civility to our ties to the People’s Republic, let us talk some sense: This was the advertisement before Blinken and Sullivan arrived in Alaska for two days of talks in a hotel ballroom—at the Captain Cook Hotel, if you please.

Those who entertained such expectations were all wrong. Biden’s national security and foreign policy people inherited the Pompeo legacy and indulged fully in it—in part, I sensed at the time, because they had no idea of an alternative policy and in part because the Democratic policy cliques never truly objected to much of what Trump’s people did.

In Anchorage, Blinken and Sullivan spent the encounter berating the Chinese about you name it—human rights, a free press, Taiwan, the Uighurs, Hong Kong protests (as backed by the U.S.), and all else falling under the rubric of “freedom.” They had nothing to say about removing the Trump-era tariffs or sanctions—or any other shift in policy. And thereupon the lights went dim in U.S.–China relations. I have long counted those two days as an historically significant turn in the bilateral relationship.

In the ensuing two years, a succession of Biden officials have gone to China to repair the damage. The formula, ever the same, amounts to what I call the three “C’s”: cooperation on the low-hanging fruit (climate, global health, international crime), competition on the trade side, and confrontation—with Tony’s “guardrails,” of course—on Taiwan, in the South China Sea, on security altogether at the western end of the Pacific. I have lost track of how many times Biden’s national security people have tried on the three “C’s.” And I have wondered how often and how bluntly the Chinese need to say “No” before the message gets across.

Not often enough, it seems. Blinken avoided saying pretty much anything during his time in Beijing this week. But you come away with the impression the three “C’s” remain his template.

■

“The international economic order that emerged in the second half of the twentieth century,” Sullivan told his audience at Brookings April 27, “no longer serves all Americans as effectively as it must.” He meant it no longer serves the hegemonic ambitions of the Beltway policy cliques, of course, but let us not sweat the small stuff. America is beginning to lose out. The world is overtaking its post–World War II paradigm: This was Sullivan’s starting point when put in English too plain for one of Sullivan’s positions to utter.

Sullivan and the rest of Biden’s foreign policy, economic policy, and national security people are late to this realization, to state the obvious, but good enough they are at last on the right page. China’s determination to construct “a new world order,” a broadening distrust of U.S. motives and intentions, the increasingly dense network of economic partnerships and alliances among non–Western powers, the swift emergence of organizations such as the BRICS and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, the SCO—all of this has been hard to miss over the past year or so.

The strange thing about Sullivan’s speech and the “doctrine” it outlines—and this is truly strange—is that Biden’s national security man can acknowledge that the history’s wheel has turned and the world along with it, only to follow with the thought that America must reclaim its leadership position as if the world is waiting for the U.S. to unchange it by reinstating America as global leader. It is worth noting this because it is the quintessence of the reigning irrationality among the D.C. policy planners. People such as Sullivan seem to think they can sit in Washington offices and dream up such plans without any need to reference what people may think anywhere else—people such as, oh, I don’t know, Xi Jinping.

The doctrine—and a lower-case “d” for you, Jake—comes in two parts. Sullivan proposes “to more deeply integrate domestic and foreign policy.” The main feature here is a now-familiar call to rebuild the American middle class to restore America’s competitiveness. Do not rise from the sofa, readers: Sullivan names no specific policy measures in support of this cause. He also wants to draw America’s “partners around the world” into this project. “This moment demands that we forge a new consensus,” he says.

This was a very indelicate thing to say, given its echoes back in the triumphalist 1990s, when the neoliberal Washington Consensus ruled and most of the world smoldered resentfully as Americans imposed it. Sullivan, twigging to this, covers himself as follows:

Now, the idea that a “new Washington consensus,” as some people have referred to it, is somehow America alone, or America and the West to the exclusion of others, is just flat wrong. This strategy will build a fairer, more durable global economic order, for the benefit of ourselves and for people everywhere.

A fairer world for universal benefit? I can’t possibly take Sullivan seriously when he proposes such things, as there is nothing in the record to support this contention. But what I think is not Sullivan’s problem. His problem is the rest of the world will not take him seriously, either. U.S. officials will be ever more compelled to say such things given the profound shifts in the global order that characterize our time. But few are likely to put any faith in this kind of rhetoric (which is all it is). This is ever the ideologue’s problem, and there is no disputing Sullivan is one: Everyone knows ideologues cannot change in the face of new circumstances.

Keep this thought in mind as you consider Sullivan’s summation of his proposed economic strategy:

The United States, under President Biden, is pursuing a modern industrial and innovation strategy—both at home and with partners around the world. One that invests in the sources of our own economic and technological strength, that promotes diversified and resilient global supply chains, that sets high standards for everything from labor and the environment to trusted technology and good governance, and that deploys capital to deliver on public goods like climate and health.

On the domestic side, Sullivan calls for restoring balance in the economy so the middle class can recover from the ravages of the past few decades, domesticating or otherwise securing supply chains, investing heavily in infrastructure, innovation, and clean-energy technologies, and protecting “foundational technologies,” high among them semiconductors. Politically, Sullivan makes a wholly frivolous plea for “Congress’s bipartisan partnership … to support this vision.”

You can get away with saying such things only if you maintain your altitude at 35,000 feet.

While I am not a reductionist, Sullivan’s program, in its domestic and international dimensions, seems in large measure a response to China’s economic and technological advances, along with Beijing’s design for a rebalanced global economy. Biden’s top security adviser proposes “necessary restrictions on specific technology exports, particularly to China, while seeking to avoid an outright technological blockade.” Further on in his remarks Sullivan states, “The administration intends to maintain a substantial trade relationship with China, striving for responsible competition and cooperation in areas like climate change, health security, and food security.”

This is what we’re now referring to as “de-risking.” As Sullivan points out it’s the coinage of Ursula von der Leyen, president of the E.U. Commission, and we find three things wrong with it. One, “de-risking” is merely a disguised admission that “de-coupling,” the previously fashionable term, was never more than an impossible dream entertained by geopolitical ideologues with a poor grasp of 21st century economics and the realities of globalized production.

Two, in all of this Sullivan makes no mention whatsoever of the Taiwan question, the tariffs, the waves of sanctions, the military buildup, and on and on. What kind of a doctrine is this? Sullivan is very handy with the airbrush, you have to say.

Three, we are back with the three “Cs,” aren’t we? We are, indeed, even further back. What is Sullivan’s “Renewing American Economic Leadership” speech if not a call to Make America Great Again?

Once again, the Chinese will have to say “No, thank you,” although their patience with the Biden administration has grown very thin these past two years and they are not putting it so courteously these days. At the just-concluded Shangri–La Dialogue, an annual gathering of Pacific Rim defense ministers in Singapore, Li Shangfu, China’s defense minister, all but slammed his hotel room door on Lloyd Austin when the American defense secretary suggested a conversation on the sidelines.

Antony Blinken just avoided another disaster in Beijing, but only by avoiding more or less everything that matters between China and the U.S. Jake Sullivan seems to be content to travel further on his road to nowhere interesting or useful. Where will this administration go now in this most vital of relationships? Maybe talking for the sake of talking, with the occasional guardrail set in place, is the best Biden and his people can do. It is pitiful, but so much about Biden’s foreign policy is, after all.