Patrick Lawrence: The Causes of Things

Casus belli

Over a summer sup on the back lawn the other night, a Times-reading, MSNBC–watching, NPR–listening neighbor asked what I thought she should read to acquire what she is not getting from these media, an accurate understanding of what goes on in our world. I loved the question: It suggested a healthy lapse of faith. Somebody else, I thought, is cottoning on to the fact that something is missing in her daily sources of information.

I named some independent publications and webcasts, ScheerPost high among them. But I reflected afterward that this reply was incomplete.

The outsized responsibilities of independent media are plain enough given the utter mess the corporate-owned press and broadcasters have made of themselves since, in my estimation, the interval following the tragedies of September 11, 2001. We reach a point when it is simply impossible to grasp the events that define our world without the reporting and analysis to be found in non-corporate, non-mainstream media. These media are plentiful, uneven, and essential now. I say this quite apart from my place in the profession.

But it is also a matter of learning how to read, view, and listen to the mainstream publications and networks, for they, alas, still flood our public discourse, they still define the national consciousness. It is best to know with what they flood us.

I would have told this admirably curious neighbor to begin with four words: “Keep reading what you’re reading. You may as well know the orthodox line. But always watch out for the history, context, chronology, and responsibility attaching to a given development. Are these present or absent in the reporting?”

In other words: What is the pertinent history as I read about A, B, or C? In what context did the present circumstance become the present circumstance? What was the order of events—when did this, that, and the other happen? And who set these events in motion? Who is responsible for what I am reading about what happened yesterday?

History, context, chronology, and responsibility coalesce to suggest my favorite word of all, causality.

The New York Times and the other major dailies—and The Times effectively tells the other major dailies what is kosher to publish of a given day—are not short of outright lies: There are no Nazis in Ukraine. The Kremlin’s intent is to rebuild the Soviet Union. China is aggressing in East Asia. Cuba is a nation of 11 million unhappy people. Those who sought to bring down the Syrian government were—infamous phrase at this point—moderate rebels. These are lies, open and shut.

But outright lies carry the danger of exposure: “They lied and we caught them!” Omission, often paired with distortion, leaves nothing for the critics to hold up to the light, nothing to discredit.

I have for years referred to this practice as POLO, the power of leaving out. POLO has been part of American media’s repertoire since the Cold War decades. The distinguishing mark of our time is that the habit of omitting is now institutionalized. It is no longer a question of what is erroneously missing in a news report. The omission of all that I have noted—history, context, chronology, responsibility, and at last causality—is now a daily occurrence.

In my years as a correspondent, you got hell from your foreign editor if you left out pertinent facts and background. Nowadays you are more likely to get hell for putting them in, and they will take them out on the foreign desk so your story conforms to “the narrative.” Omission—and it is time for someone in the profession to say this—is an insidious form of lying, akin to passive aggression, that most intractable of neuroses.

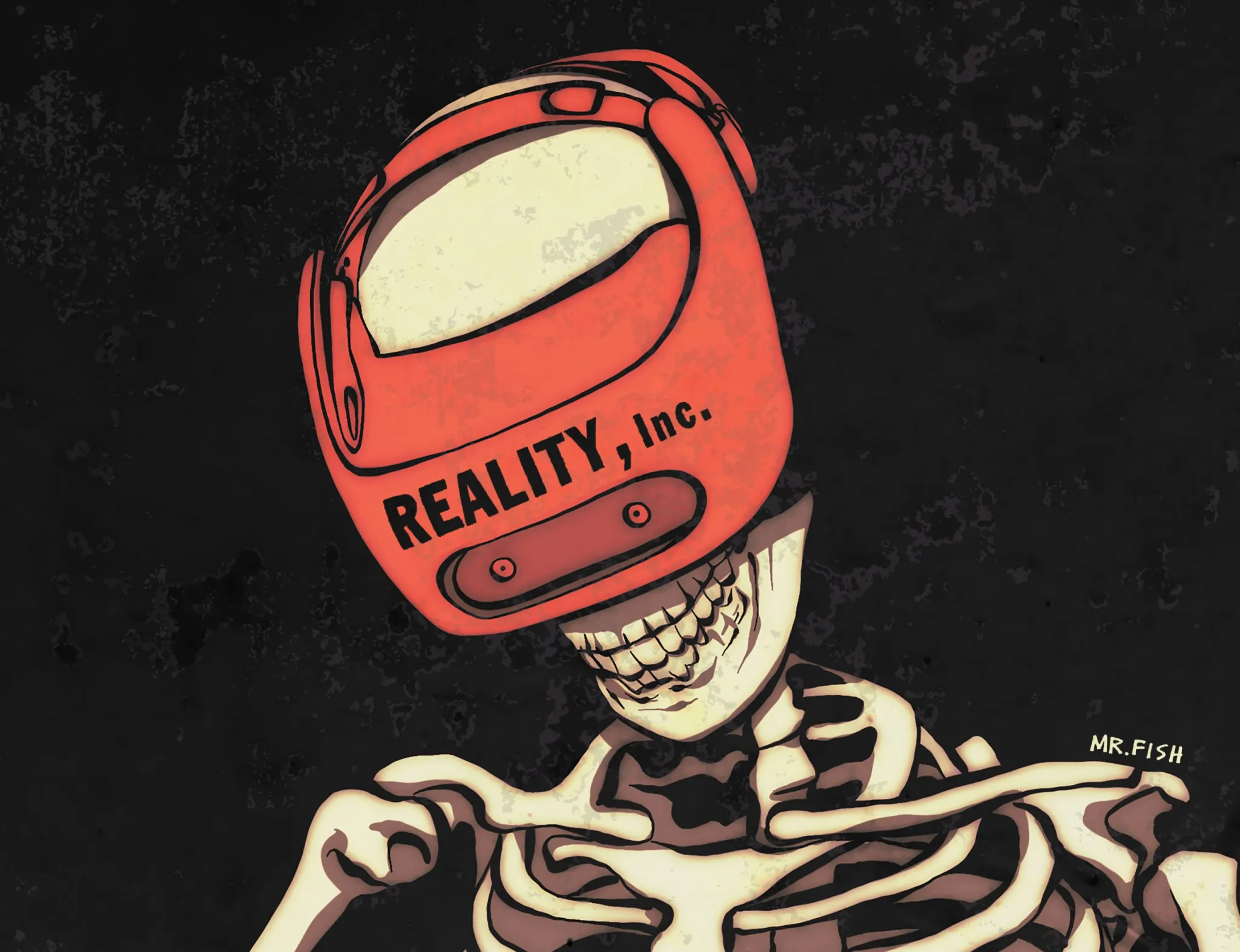

I am telling you this because the game of POLO is now so universally played that it is changing our already troubled republic into a nation dangerously ignorant of the world as it truly is. I say dangerously ignorant because in this condition, those purporting to lead us are effectively unchecked by the force of public opinion. I leave it to readers to choose the term that defines this kind of society.

I step back and realize most Americans have no clue of the history, context, and all else that bears upon the Ukraine crisis. NATO’s eastward expansion, Washington’s long effort to turn Ukraine into a forward base on Russia’s doorstep, Moscow’s 30–year effort to negotiate a mutually satisfactory security order in Europe, the Kiev regime’s fanatical—not too strong a term—Russophobia: All of this is left out.

From a ripe orchard of examples illustrating the practice of POLO as it is played day to day, I choose a much-noted speech given last week by Sergei Lavrov, Russia’s long-serving foreign minister, to Margarita Simonyan, the editor-in-chief of RT, Russia’s equivalent of the BBC. It was reported by RIA–Novosti, a government-funded wire service.

This was an important occasion. Lavrov announced that Russia’s objectives remained the same but its strategy was evolving and offered an explanation as to what has prompted this evolution. Lots of media reported on Lavrov’s remarks, so we know what he said and what the American press, The Times per usual in the lead, left out, distorted, or reported and then erased. In this case, it did all three.

“Everyone in Russia wants to know when this war will end…. Where do you think it will end—where will it end geographically?” This was Simonyan’s key question.

Lavrov replied that Russia’s objectives remained as initially stated—to de–Nazify and demilitarize Ukraine “that there are no threats to our security, military threats from the territory of Ukraine. This task remains.”

He then addressed the “where” question. “Geography-wise, the situation is different. It is far from being only the DPR and LPR [the Donbass republics]. It is also the Kherson region, the Zaporozhye region, and a number of other territories” — all three west of the Donbass. Significantly, as in very, Lavrov did not, when asked, rule out the expansion of the Russian operation through to the western city of Lviv—in other words, all the way to the other end of the country.

Lavrov was very clear as to why Russia’s thinking had changed. The arrival in quantity of advanced artillery known as HIMARS, highly mobile advanced rocket systems, means that to protect itself against threats to its security Russia would have to demilitarize all territory within the range of these systems.

It comes to simple arithmetic: The most advanced HIMARS units have a range of 300 kilometers, not quite 200 miles. As the U.S. continues to supply the Kiev regime with increasing numbers of these, the Russian military will have to go commensurately further into Ukraine to secure itself from attack. This was the most important point Russia’s top diplomat wanted to make.

Let us state this simply: The U.S. and its NATO allies will prolong and expand the Ukraine conflict so long as they continue flooding the nation with advanced, long-range weaponry. Cause, responsibility, effect. Not too complicated.

In its July 20 report on the Lavrov interview, The Times could not simply omit entirely an account of Lavrov’s reasoning. It was too widely reported. There are occasions when the POLO strategy requires slight elaboration, and this is one of them: You report it, distort it, then erase it best you can.

From The Times report: “He pointed in particular to multiple rocket launchers that the United States has begun delivering to Ukraine, which have been credited with slowing the Russian advance by hitting faraway targets like munitions depots.”

Fine. True. Next paragraph: “But Western officials have always scoffed at Moscow’s claims that its invasion is anything less than an act of expansion—an attempt to reclaim territory lost with the fall of the Soviet Union.”

Not fine. Not true. The Times report goes on to assert that we must not trust Russia’s explanations for its intervention in Ukraine because they are always changing and do not make any sense. Not remotely true. They make eminent sense so long as you bear in mind my four words plus one: How did things come to this and who is responsible for it.

Into the dark Times readers are again plunged.

Next time I see my kindly neighbor I will tell her: Read The New York Times or listen to NPR, which customarily recites the front page of The Times in its newscasts, to know what you are supposed to think happened. Then go in search of an account of what happened.

Why does our century end?

Harper’s has done us all an enormous favor. Its July cover story carries the headline, “The American Century Is Over. What’s Next?” atop a lengthy piece by Daniel Bessner, a scholar at the University of Washington. Andrew Bacevich, the author of many notable books on the American imperium, has done us another. In a piece responding to the Harper’s essay, first published in TomDispatch and reprinted in Consortium News, where I read it, Bacevich ruminates usefully on Bessner’s question. His piece appears under a wonderful head: “Imperial Detritus.”

I have been on the edge of my seat for years about this. And at last the topic finds its place in our public discourse. Not only can we now think critically about Henry Luce’s “American Century” without risking universal opprobrium; we are all of a sudden talking in public places about its end while wondering what might come next.

I see this as a potential opening. I do not know what kind of comment or discussion the Bessner and Bacevich pieces will precipitate, but this is not precisely the point. Whether or not they get the attention they deserve, these are voices of the times.

I would place these two on the outer rim of acceptable discourse. Were LBJ weighing in, he would say they’re inside the tent urinating out. Fine. A few years ago this kind of work was limited to those outside the tent urinating in. The sun gradually rises upon our American darkness. The thought that we may find our way out of the eternal present that entraps us and think about a different future is not much short of intoxicating.

Luce, of course, was the influential publisher of TIME and LIFE and famously declared “the American Century” in a much-remarked editorial that appeared in the latter magazine in late 1941. He had in mind a certain kind of America when he named a century after it—a powerful America, an exceptional America, a capitalist America, a corporatized America, an ideologically driven America.

Bessner is very fine as he captures the sheer hubris of Luce’s notion. I was especially pleased to see he fished out that extraordinary passage in the editorial wherein Luce asserted that Americans must “accept wholeheartedly our duty and our opportunity as the most powerful and vital nation in the world and… exert upon the world the full impact of our influence, for such purposes as we see fit and by such means as we see fit.”

Our republic was destined to be “the powerhouse… lifting the life of mankind from the level of the beasts to what the Psalmist called a little lower than the angels.” Jeez, if I may say so. People such as Luce said things like this in public back then.

But if you think this stunningly crude and arrogant, pause for a sec: Luce said it, everyone with a good job in Washington still thinks it and acts on it. The news Bessner and Bacevich have to deliver in these pieces is still… news to them. Isn’t there some outfit called Project for a New American Century and am I right to assume people take it seriously?

The dissident colonel, as Bacevich is known in this household, was right to point out that Bessner is amiss in not noting Luce’s religious background. It is key to the story, as the above passage suggests. The son of missionaries in China, Luce had a messianic dimension in his thinking that cannot be overlooked if we are to understand the man and what he stood for. Remember, TIME editors routinely turned the files of their China correspondents into propagandistic mush when they reported accurately during and after the “who lost China?” years following Mao’s arrival in Beijing in October 1949.

Bessner and Bacevich share credit for judging the American Century a failure waiting to happen from its inception. “The more one considers the American Century, in fact, the more our tenure as global hegemon resembles a historical aberration,” Bessner writes. “Geopolitical circumstances are unlikely to allow another country to become as powerful as the United States has been for much of the past seven decades.”

Exacto, Daniel. I see no nation that aspires to any such debilitating position. Empires are a 19th century Western technology. If I read history correctly, America’s may turn out to be the last humanity must suffer.

Here I depart from Bessner’s thesis. He argues that “two transformational events have begun to reshape the United States’ place in the world.” One is Donald Trumps’ victory at the polls in 2016, and the other is China’s emergence as a regional and, let us face the music here, a global power.

One, I am not on for Donald Trump as the personification of American decline. This is liberal escapism. Our 45th president was a symptom, not a cause, and was not entirely devoid of good ideas. The Biden regime, indeed, is leaving these aside while picking up intact all the bad ones.

Two, external factors, or exogenous factors if we want to include the Trump phenomenon, are not what cause the beginning or the end of anything. They are manifestations of underlying realities in the way politics is at bottom an expression of culture, or a society’s lack thereof I suppose I should add.

The American Century did not end with Donald Trump’s emergence in national politics or with China’s immense success in rising out of poverty and making itself an influential nation. It ended, in my judgment, with uncanny precision on the morning of September 11, 2001, leaving us with a 60–year century.

Here I go to Toynbee, the out-of-fashion historian, and I confess a peculiar taste for out-of-fashion historians (and a distaste for academic fashions). Toynbee asserted that civilizational decline is the result of inner, spiritual collapses, lapses of belief in those drives and purposes that push societies confidently on, whatever the validity of these drives and purposes. This is what happened on September 11. The nation that thought of itself as immune from the forces of tawdry human history and time suddenly discovered it was subject to both. The hand of Providence failed to come down from the clouds.

I was there to watch this, as many readers surely were. Tragic as were the fatalities that day, the greater deaths were of spirit, of belief in ourselves and our story. That endlessly looped footage of the planes as they piled into the World Trade Towers: That was our objective correlative, our way of watching and mourning what we had just lost.

A dozen years later, in Time No Longer: Americans After the American Century, I made my case for September 11 as the true ending of the interim Luce named. I hold to it. All America has done since, all the messes, illegality, and grandiloquence, has been in the way of forlorn denial. The Biden presidency reminds me of García Marquez’s Autumn of the Patriarch. The man is perversely perfect for our moment.

Bessner sees the post–2016 discourse as divided between liberal interventionists and the “restraint” crowd, he a member of the latter. This is fine, but I do not think his conclusion is. “For those of us in the latter camp,” he writes, “the withering away of the American Century cannot be reversed; it can only be accommodated.” This is not, to put my point mildly, an occasion for an accommodation of the past. We simply do not have time for it. I have often wondered whether the truth is always radical. I have no answer to my question except to say it certainly is in our time.

The dissident colonel has a better handle on our moment. “Better in my estimation to give up entirely the pretensions Henry Luce articulated back in 1941,” he writes. “Perhaps it is time to focus on the more modest goal of salvaging a unified American republic. One glance at the contemporary political landscape suggests that such a goal is a tall order. On that score, however, reconstituting a common moral framework would surely be the place to begin.”

Indeed, Andrew. But what is the matter with tall orders?

What we must next push into the discourse is a nice, fulsome conversation under the heading, “post-exceptionalism,” a topic I have explored at length elsewhere. By this I mean a new understanding of ourselves and our place in the world—altogether a new consciousness. This is what truly must come next if anything else of worth is to follow.

In the mean, let us thank these two writers for pushing us along in the only direction we can go if we are to do well in our new century, everybody’s century.

What a delightful moment to read your prose Mr. Patrick Lawrence! When one stands close to America but a foot (or so) outside the American “fantasy” of exceptionalism: speaking French in Québec permits anyone educated that Europe’s repetitive declines -for us, here, notably France’s symptoms of inevitable Fall since 1815, with our outsider position helps a lot in this quagmire task of noticing the symptoms of decline. After experiencing these declines, three in total-I will name them shortly below, one can relate to what you are explaining so clearly. On the subject of Ukraine, as we are entangled into these illusions of perceptions poorly maquillées, I wish you could read Jacques Baud’s book entitled “Poutine maître du jeu ?” because the question mark at the end is of crucial importance in the final answer he helps us ascertain.

Like you, in all 3 languages I have attempted to master in my lifetime, I m dismayed by the distortions and the lack of method in the corporate media, that this fundamental quote from your comment outlines when these four omissions occur and are lamentably absent: “History, context, chronology, and responsibility coalesce to suggest my favorite word of all, causality.” They are simply always left out. But, rejoice with me, on Ukraine they are underlined and explained in full in Jacques Baud s recent book (Feb.2022, one ought to await the coming next one this September 2022- I doubt anyone courageous enough to propose and realize a rapidly effective or properly needed translation in English).

Noticeably, how lucky your neighbou is, that is so fortunate to come chat with you for supper…should simply- if any light or sensitivity to profoundness animates her or his- brain-simply to be able to consult with you and feel assured of finely directed in well intended guidance. Hence, this second passage from you is very good counselling :”Read The New York Times or listen to NPR, which customarily recites the front page of The Times in its newscasts, to know what you are supposed to think happened. Then go in search of an account of what happened. ” I now have one last comment to add.

As for the moment of decline for America, I hesitate between the Truman presidency and the Reagan presidency for the intensity level of the lies that came to light constantly. The 8-year-presidency G.W.Bush-Dick Cheney were the extreme years of dismay worldwide before the 8-year Obama deceit in such grand-elegance-style of lying with chic…already there since Truman’s first term as proof of the advanced gangrene incurred by the mob running your “holy land” or attempting to defend it by invading others in maniacal ways. It helps me, from Montréal, to have been able to visit Cuba many times before figuring out how it has been a deafening response in kind, sometimes in the worst “counterexamples” to the horrible soloist of greatness in the Halls of NATO, the UN, or the “organisation des États Américains” or any other acoustically astounding places where this US tenor among nations, namely POTUS, searched for applauses (genuine ones or the ones paid for).

Finally, I’m extraordinarily happy to have discovered you like I once discovered Patrick Seale’s books on the Middle-East or Jacques Benoit-Méchin’s entire production on so many subjects of history…And you are so witty in saying or writing this: “If I read history correctly, America’s may turn out to be the last humanity must suffer.” Imagine, yes the suffering caused worldwide by the USA just recently under Nuland-Rice-Powell-H-Clinton in World Affairs but since it began mingling in tempting hegemony (the First World War 2 terrible treaties of Versailles and saint Germain or even perhaps as far back when it established its Monroe doctrine) and not carefully respecting its original desire not to take part in wars abroad . Hegemony is always tantalizing and tempting and, hypocritically, Canada has surfed on the Greatness of 3 recent empires it associated itself with as a colony: France’s hegemony (till 1760), Great Britain’s hegemony (till 1940) then the USA’s apparent hegemony (till February 2022 shortly after Monsieur Biden’s strange overnight triumph despite Ben Shreckinger’s prudent but incisive recent book on this appalling powerful triumphant influential “family”).

I hope some students have benefitted of your excellent mind and analysis over the course of your career about which I know little but that I can wholeheartedly appreciate here, with irony and laughter and this je ne sais quoi of yours!