“A post-imperial language.”

Conversing with novelist Peter Dimock.

Ray McGovern, who I count a dear friend and supporter, once observed in one of his speeches that it’s not enough to dwell on the incessant rains that fall upon us. The true task is to build arks. The thought, the challenge, has ever since remained with me. What do we do, what else, as we advance our critique of empire, as we seek to unbury our humanity from empire’s crumbling edifice? What are our cultural productions—the things that express us as we are, that speak in our language, that bring beauty into our lives? What is our art?

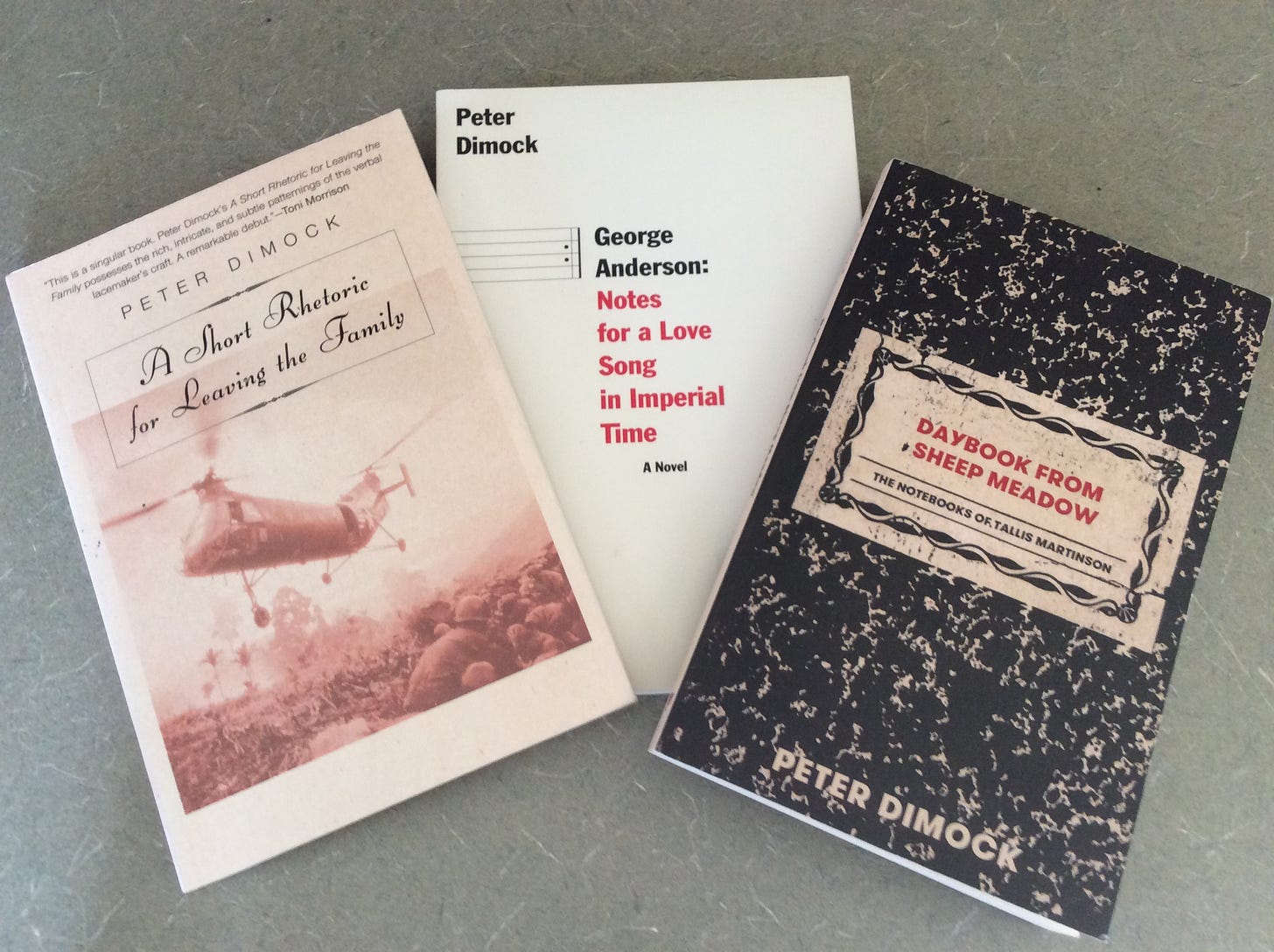

Peter Dimock, in my view among the (very few) distinguished novelists of our time, answers these questions with originality, elegance, and a refined mastery of prose few other writers of our time match. He answers them in his three novels to date, A Short Rhetoric for Leaving the Family, 1998, George Anderson: Notes for a Love Song in Imperial Time, 2012, and Daybook from Sheep Meadow: The Notebooks of Tallis Martinson, which is now out from Deep Vellum Publishing, a discriminating house publishing in Dallas.

And he answers our questions again as The Scrum welcomes him to its pages.

I have loved these books as each has come out, in truth. As we explore in the webcast The Scrum recorded recently, these are masterworks in dexterous writing, ranging by turns from the hardly factual, the nearly documentary, to the tenderly lyrical. In Dimock’s latest, the prose is at times (as I read it) best understood as poetry. All three novels are formally innovative—challenging, this is to say, in a way that draws us in rather than sends us away. Most of all, they have a quality I have mentioned to Dimock many times in the course of our long friendship: They never lose sight of politics, of history, of our late-imperial predicament. They do not flinch.

I have come to consider these novels a trilogy now that Daybook is out. They share a commitment to new forms. They are written from a common perspective: There is a divide implicit in them, a sort of “before” and “after,” if I do not put this too simply. We live amid the ruins of empire, they say. How do we think and act and speak in a new way? Central to each of the books is a search for a new language, a post-imperial language as I think of it, such that we may know ourselves, speak honestly among ourselves, redeem our past and ourselves by way of a new path forward.

Without this new language, Peter Dimock seems to say, we will not be able to act as we must. In his three novels, he takes us on the search for this language and suggests what we will sound like as we discover it.

—— P. L.