“The ‘sacred outcast.'”

Assange behind glass. Part 3.

The Scrum concludes publication of an extended essay on the Julian Assange case that first appeared in Raritan, the quarterly journal. Proceedings at the Royal Courts of Justice in London, during which the Crown Prosecution Service presented the American case for overturning the earlier judgment against extradition, have ended. A new judgment is to come in several weeks. We along, with many, many principled and loyal supporters and advocates in many countries around the world, await it.

Part 1 of this essay, “Shards of a shattered life,” can be read here, and Part 2, “‘The experiment in total domination,’” here.

SINCE ASSANGE’S FIRST MOMENTS in captivity, when a half-dozen police officers carried him down the Ecuadoran Embassy’s steps, the corporeal dimension of the state’s conduct has been very plain. This we must also consider. If the project is total domination, it must begin with the body. It is through the body that the prisoner is deprived of all control. Guantánamo Bay, Abu Ghraib, the C.I.A.’s secret torture sites, Chelsea Manning at Quantico and Leavenworth: There are many such cases, these merely the most readily to hand. The excessive use of prolonged solitary confinement at “supermax” prisons across the United States constitutes another. Bodily domination as a coldly efficient means of dehumanization, of assault on all constituents of identity: From the time of the camps until today, it is always in evidence. This is what we look at when we look through the glass at Assange.

It would be illusory to posit that this use of the body is something new in the Western democracies. Slavery, the American Indian campaigns, the World War II internment camps: These are obvious precedents. But in this contemporary iteration we nonetheless find an unprecedented descent into convergences with some of the most detested features of the West’s twentieth-century totalitarian adversaries. Routinized torture, the pervasive reach of surveillance into the spaces of daily life, lately the systematic punishment of innocent populations by means of diabolically calibrated sanctions, and now what amounts to the physical and mental abduction of those challenging the vast universes of sovereign secrets—all of this must concern us partly as a matter of morality but also because we are subject to it ourselves. We watch as our sovereign institutions, one after another, destroy themselves with illegitimate assertions of sovereignty. While once we looked to them for protection, we—we, all of us—must now seek protection from them. This is the lesson Assange in captivity has for us.

Nowhere is this of graver consequence than in the case of our judiciaries. It is when judicial systems lapse that a society’s final fate becomes evident. Judges and courts are the last line of defense against “failing state” status. We must consider Vanessa Baraitser’s imperious performance in this context. With her flagrant corruptions of due process and her high-handed demeanor, what is it she sought to convey, seated as she was in an English judge’s robe and peruke?

The relationship between law and lawgiver has preoccupied many a political philosopher over many centuries. In the modern West, where the citizenry is declared sovereign, those who make law and enforce law are assumed to be bound by law. It is difficult to think of Baraitser as a Cicero-reading legal scholar, but she nonetheless took a strong position as to the purview of law. By word, gesture, and deed, she placed the giver of law outside the law. Those who consider this question in our time, Hannah Arendt and Giorgio Agamben among them, define this as a “state of exception.” Sovereign power declares itself the exception to its own laws. This leaves the state inside and outside the judicial order at the same time, for it cannot be an exception unless there is a judicial order from which it is excepted. The sovereign extends law over the governed, in other words, so as to demonstrate its position above it. Agamben expresses the paradox this way: “I, the sovereign, who am outside the law, declare that there is nothing outside the law.” This is Baraitser’s implicit but very clear position: I, Judge Baraitser, embody the law and enforce it. I am not bound by the law I uphold.

“Everything is possible,” is among Arendt’s better-known interpretations of conditions in a totalitarian state. This, a state of exception par excellence, is the defining objective of total domination, she tells us. Arendt is writing about the sovereign’s claim to infinite prerogative, to put the point another way. Baraitser’s claim to sovereign prerogative is quite the same. Everything was possible in Baraitser’s courtroom—or, at the very least, no limit to the possible was tested. Are we not on notice that we all live within this condition? The sovereign can torture and it is not torture: Assange in captivity demonstrates this plainly enough. At the extreme—and the extreme has been reached numerous times in numerous cases—the sovereign can kill and it is not murder.

■ ■ ■

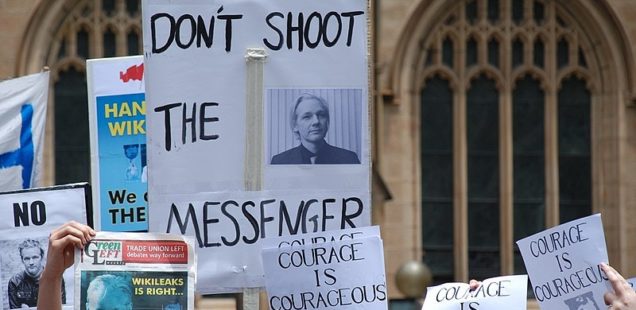

NOT LONG AFTER Julian Assange’s arrest, an organization called Speak Up for Assange began circulating a petition asking journalists to support “an end to the legal campaign against [Assange] for the crime of revealing war crimes.” The document is offered in eight languages. At writing [Spring 2020] it bears fourteen hundred signatures, mine among them, from ninety-nine nations.

To gather fourteen hundred journalists in behalf of Assange is an excellent thing. But when we put this number against the number of journalists in the ninety-nine countries cited—there are more than thirty thousand in America alone—we must draw a different conclusion. Where is everybody? we must ask. What happened (and when), such that the press that welcomed Assange and WikiLeaks after its founding in 2006 came to evince nearly rabid animosity toward both?

If 2010 marked WikiLeaks’ coming of age as a publisher, it was also the year the American press, along with media in Britain and elsewhere, began to turn on their former colleagues. The precipitating event was the October publication of “Iraq War Logs.” It was on this occasion that official Washington established three long-running themes: WikiLeaks risks American lives; WikiLeaks compromises national security; WikiLeaks aids those the United States deems adversaries. The American press concurrently began to shift its attention from the publications it had enthusiastically reproduced to WikiLeaks and its founder. Reports of internal dissent, financial difficulties, and Assange’s allegedly abrasive personality date to this time. An unrelenting campaign of character assassination had begun.

In the ensuing years the press and broadcasters have treated us to a truly preposterous list of Assange’s shortcomings, disorders, excesses, and perversities. He is a rapist, a narcissist, a megalomaniac, a fascist. He is a liar, he is unwashed, and he did not clean his bathroom at the Ecuadoran Embassy—where he mistreated his cat and smeared feces on the walls. Caitlin Johnstone, the irreverent Australian commentator, gathered twenty-nine such entries and offers replies to them as her contribution to In Defense of Julian Assange. To read her list is to confront the extent to which American media have made a pitiful mockery of themselves, a juvenile spectacle worthy of Lord of the Flies. Entirely out the window, of course, is any further consideration of the war crimes and corruptions reported in “Iraq War Logs” and other releases.

On 13 April 2017, shortly after President Trump named him director of the C.I.A., Mike Pompeo addressed the Center for Strategic and International Studies, the Washington think tank. Pompeo devoted a remarkable proportion of his speech to WikiLeaks and Julian Assange. This reflects the timing of Pompeo’s CSIS presentation. Less than a year earlier, WikiLeaks had begun publishing mail stolen from the Democratic National Committee’s computer servers. By the time Pompeo spoke, the convoluted, devoid-of-evidence fable we call “Russiagate”—a cockeyed conspiracy theory if ever there was one—was fixed in the American consciousness. “It is time to call out WikiLeaks for what it really is—a nonstate hostile intelligence service often abetted by state actors like Russia,” Pompeo asserted.

This was Pompeo’s essential message that day. The press and the broadcasters turned Pompeo’s comments into headlines, and another groundless bit of fabrication was on its way to being accepted as fact. The conjured connection with Russia was key. It was not a tossed-off comment or a matter of loose name-calling on Pompeo’s part. His designation opened the way, legally speaking, for the U.S. to pursue Assange under the Espionage Act. In this Pompeo signaled a grave escalation of the confrontation between Assange and the American government. And his speech that day licensed many in the press, and I would say most mainstream media, to abandon Assange, so finishing what it had begun years earlier: Much that we find on Johnstone’s list of slurs dates from the time since Assange was identified as neither a journalist nor a publisher but as a foreign agent with some indeterminate tie to Moscow.

In Defense of Julian Assange gives us an excellent, well-edited record of a pilgrim’s progress as he fights our very necessary war against runaway secrecy in defense of properly democratic societies whose governments operate transparently. Daniel Ellsberg, Patrick Cockburn, John Pilger, and Matt Taibbi are among the book’s many distinguished contributors. Renata Avila, a Guatemalan human-rights lawyer who has represented Assange over many years, writes a cogent account of meeting Assange (in Budapest, 2008), during which he explained WikiLeaks’ working principles: decentralization, security (of staff and documents), and protection of sources. Stefania Maurizi, an Italian journalist and longtime WikiLeaks collaborator, describes, albeit discreetly, the organization’s operations from the inside out. There are repeated challenges to the by-now-baroque edifice of falsehoods erected to turn Julian Assange into one of the repellent malefactors of our time.

■ ■ ■

IF IN DEFENSE OF JULIAN ASSANGE offers a factually sound understanding of the WikiLeaks founder and the truth-seeking tradition he stands within, it is also useful as a mirror to reflect upon the commonly accepted story of the man and his work. To read the book is to recognize that our corporate media’s over-the-top renderings of Assange are best understood as “persecution texts.” This term belongs to René Girard, the late philosopher and social critic. Persecution texts are accounts of transgressions told from the perspective of those persecuting the transgressor. They typically combine the real and the imaginary, the true and the false, and they are reliably replete with “characteristic distortions.” Of these distortions Girard tells us something very useful. Even if they are ridiculous (as in the Assange case), there is much to learn from them. The more ridiculous the text, Girard finds, the more it tells us about its authors. “The unreliable testimony of persecutors,” Girard writes, “reveals more because of its unconscious nature.”

Our question is clear. What do the very numerous persecution texts available to us reveal about the media that compose and publish them? It is not enough to see the pitiful and juvenile in press reports of scatological doings at the Ecuadoran Embassy, or of cruelty to a house cat, or of an unclean loo. These are texts. What do we find as we interpret them?

In the American context, our media have made Assange the object of a purification ritual. In this his persecution—and so I will call it—is in line with the Quaker hangings in Boston, 1659–1661, the 24 Salem witch trials three decades later, the anti–Communist paranoia of the 1920s and 1950s, the Russophobia and Sinophobia that now beset us. In all such cases, the righteous community—transcendent, messianic, chosen—has been corrupted and must be regenerated, its purity restored. The polluting alien must be expelled. Hardly is it difficult to read this unconscious drive, primitive as it is, into our media’s obsessions with Assange the unclean, with Assange who is a Russian asset, with Assange who is not a journalist.

Girard would consider Assange a scapegoat in his highly developed use of this term. Assange in sequestered captivity is a sacred outcast, to put the point another way. This ever-perplexing figure has a history extending back to the Romans and has since inspired many interpretations and reinterpretations. The sacred outcast (homo sacer in Latin) is “noble and cursed,” in Girard’s phrase. He is considered worthy of veneration, but he is also a breaker of taboos and so is subversive of the established order. The admired transgressor: This will do as a thumbnail description to get us past a contradiction that is merely apparent, the holy man who must be cast out. By tradition the homo sacer, important to add, can be murdered without fear of retribution. This, too, is a feature of his fate—a point Giorgio Agamben emphasizes in Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life (Stanford University Press, 1998), his remarkable exegesis on this topic.

The sacred outcast serves an essential function. In the time before he is ostracized, the threat of division, schism, or even violence hangs over the group to which his persecutors belong. A certain hysteria commonly besets the group during this crisis phase. Ejecting the homo sacer relieves these pressures. Differences within the group are dissipated. I will return shortly to this point.

Assange as archetype: We can gain much understanding if we use this thinking—judiciously, of course—further to illuminate the media’s treatment of him. If the righteous community has banished the transgressor from its midst, what was the transgression? In Defense of Julian Assange stands with the signature-seeking website on this point: Assange’s crime is to expose the crimes of the powerful. This is fine but not enough. The press and broadcasters have impurities of their own to bleach clean. What are these?

Assange the scapegoat has departed from the originary American code. This is his irreducible violation. He broke the taboo against questioning—prominently, in public space—the essential virtue of American intent and American power. Many of WikiLeaks’ major document releases—not all—challenge this sacrosanct precept. American media, with occasional and carefully attenuated exceptions, observe it, so staying well clear of the taboo. The originary code amounts to a code of silence at this point, so many are the instances of malign American conduct that go unreported (or dishonestly reported) by our corporate-owned newspapers and broadcasters. When Assange confronts the fallacy of American goodness and innocence, he also confronts the media’s sycophantic allegiance to official orthodoxies. In effect, he exposes the media’s culpability—its collaboration in preserving the myth necessary to obscure the true nature of American power.

How shall we understand those early years, when the press readily republished WikiLeaks releases? After the publication of “Iraq War Logs,” The New York Times set up an interactive site called “The War Logs.” It featured a search mechanism enabling readers to sift through the immense inventory of documents according to topic. This was diligent journalism in the new mode. Al Jazeera was the only other newspaper to match The Times for thoroughness. It is true that The Times concurrently published news reports that erased the complicity of U.S. forces in the torture of Iraqi detainees, leaving readers to conclude the Iraqi military and police acted without the knowledge of American authorities. But the question remains: How did the press go from collegial collaboration with Julian Assange to scapegoating him as a pariah? It is a very curious journey by any measure.

American media, shelters of our indoctrinated elites, were fated from the first to face a choice in their relations with WikiLeaks and its founder. Sooner or later, working with the organization was bound to put them at odds with the institutions of power they had long and loyally served. There was the potential for conflict, crisis, or both— schism or violence in the archetypal meaning of these terms. Sooner or later, they would have to decide whether to continue observing the originary code or to transcend it, as Assange had done to such impressive effect.

The moment to choose arrived with the release of “Iraq War Logs.” So did the disavowals and demonizing begin—the casting out and scapegoating. And so was harmony restored between the press and the institutions of power it reports upon. It was inevitable that all the persecution texts would follow. Now we come to the truth of our media’s remarkable animosity toward Assange. Journalism is seeing and saying; WikiLeaks and its founder are exemplary practitioners by this, my irreducible definition of the craft. The work is to see and say in the cleanest possible fashion— with gathered facts alone, without editorial comment, without persuasion. In this way Assange stands as an ideal—never mind whether our corporate media so acknowledge him. In archetypal terms he is sacred. But Assange is also damned, for he is a traitor, just as he is accused. He is unfaithful to our mass media’s illusions, and we must consider these two ways. There are the illusions our press perpetuates in its pages, and of these there are of course very many. There are also the illusions media live within—illusions of integrity, of impeccable ethics, of principled independence from institutions of power. Mainstream media have long deceived themselves with these illusions, and it is these Assange betrays. He betrays, then, those who warrant betrayal. His every publication confronts them with what they have failed to be and do.

So is Assange banished. So should we understand his banishment. Assange has preserved the lost ideals his persecutors recognize, with unconscious but legible bitterness, as no longer their own. It is by casting him out that the righteous community averts dangerous conflicts in its ranks and restores the existing order, the troubled peace Assange has so honorably disturbed.