“‘The experiment of total domination.'”

‘Assange behind glass.’ Part 2.

The Scrum continues to publish an extended essay on the Julian Assange case. As court proceedings continue in London—a travesty of due process by any serious measure—and in the face of the shocking silence among corporate media, we offer this piece as our contribution to the admirable worldwide effort to bear witness to the WikiLeaks founder’s courage as a publisher and, since 2019, his courage while imprisoned and subjected to the monumental corruptions of the British and American judicial systems. These corruptions, as herein described, continue during this week’s proceedings at the Royal Courts of Justice.

We note that the since this essay was first published it has come to light that the CIA, well beyond its efforts to spy on Assange during his period of asylum at the Ecuadoran Embassy in London, as noted herein, was also devising plots to kidnap or assassinate him.

Part 1 of this essay can be read here.

WHISTLE-BLOWING and the exposure of the officially hidden have long and honorable traditions, in America and elsewhere. As one would logically expect, challenges to our empires of secrecy have grown more frequent along with the grotesque expansion of these antidemocratic domains. This has proceeded in consonance with the elaboration of the national-security state, beginning with Truman’s fateful directive in 1952—kept secret for decades afterward—to authorize the new National Security Agency. The imperium we now live within, we may fairly say, has from the first been a furtive, undeclared and unnamed, there-and-not-there undertaking—secrets comprising its walls. With the keepers of secrets, more or less inevitably, come the breakers of secrets.

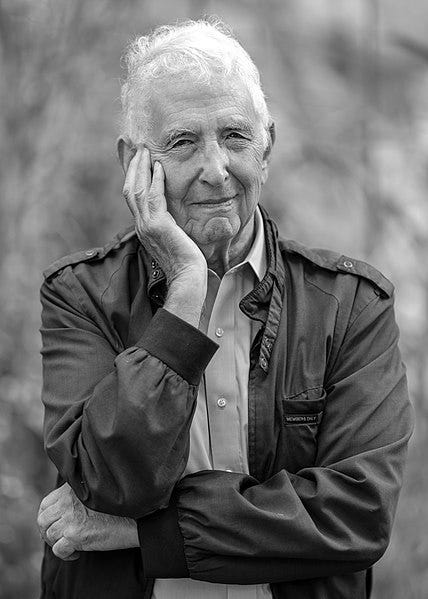

There are some illustrious names among the leakers and whistle-blowers of our recent past. Most people’s lists begin with Daniel Ellsberg, he who passed the Pentagon Papers to the New York Times in 1971. Mark Felt, a career F.B.I. official, was the Deep Throat of the Watergate scandal, although his name was made public only in 2005. Let us not forget Samuel Provance, the Army intelligence officer who exposed abusive practices at Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq in 2004, along with the attempted cover-up that followed.

The list—any good list—must go on and on, too many exemplary figures to mention. Bill Binney, Kirk Wiebe, Ed Loomis, and Tom Drake were senior NSA officials when, in the early years of our century, they exposed the corruptions associated with the agency’s now-infamous surveillance systems. These four had a curious ancestor worth noting. Herbert Yardley directed the Cipher Bureau when, in 1931, he exposed the first monitoring and surveillance practices of an early iteration of the NSA.

Julian Assange cannot properly be assigned a place on any such roll call. His work concerns whistle-blowing, but he is a journalist and publisher with no whistles of his own to blow. Assange’s bravery when confronted with questions of principle and integrity, and the magnitude of what he determined to do, are the match of anyone’s in the truth-telling tradition. But we cannot tuck Assange neatly into any file. His fate sets him apart, just as the figure we now see behind glass is apart from us. There is an historical discontinuity, too. What has been done to Assange since his arrest and detention, how, and by whom, is to be understood only by way of the most disturbing precedents. Let us call this the colonization of Assange’s being—every aspect of it—by legal authorities with (a paradox here) no legal authority to act toward Assange as they do.

■ ■ ■

ABOUT A MONTH after Assange was sent to Belmarsh, a prison Britain uses to detain foreign nationals suspected of terrorist activity, he wrote a letter to Gordon Dimmack, an activist (and self-fashioned journalist) who follows the Assange case. At the time, Assange and his defense attorneys were trying to frame their case against the American extradition request. In Defense of Julian Assange includes part of this letter. Here is a brief passage:

I have been isolated from all ability to prepare to defend myself . . . .I am unbroken albeit literally surrounded by murderers. But the days when I could read and speak and organize to defend myself, my ideals and my people are over until I am free.

This letter is dated 13 May 2019. At a preliminary extradition hearing shortly afterward, Assange’s attorneys stated that their client was too ill to appear in court, even via video from Belmarsh. On the same day, WikiLeaks announced that Assange had been moved to the prison’s hospital wing. One of his defense attorneys said at this time that on meeting Assange “it was not possible to conduct a normal conversation with him.” A day later, Nils Melzer, the U.N.’s rapporteur for torture at the time, made public his findings on examining Assange, not quite a month after his arrest, in the company of medical experts. These were the first indications that Assange was being mistreated at Belmarsh. Here is part of what Melzer wrote:

The evidence is overwhelming and clear. Mr. Assange has been deliberately exposed, for a period of several years, to progressively severe forms of cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment, the cumulative effect of which can only be described as psychological torture.

Assange next appeared in public on 21 October last year [in 2019], the date of the third image considered earlier, when he attended another preliminary hearing at the Westminster Magistrates’ Court. This was an important occasion. Craig Murray was among those in court that day. Murray, a Scot and a former Foreign Office diplomat, stands among Assange’s most dedicated supporters. The day after the Westminster hearing, he published a lengthy piece on his website. It circulated widely—no surprise given its astonishing account of Assange’s enfeebled appearance and the willful corruptions evident throughout the proceeding. I will quote Murray’s report at length. His language, along with the images he conveys to us, merit our close attention:

I was badly shocked by just how much weight my friend has lost, by the speed his hair has receded and by the appearance of premature and vastly accelerated ageing. He has a pronounced limp I have never seen before. Since his arrest he has lost over 15kg [33 lbs.] in weight. But his physical appearance was not as shocking as his mental deterioration. When asked to give his name and date of birth, he struggled visibly over several seconds to recall both. . . . It was a real struggle for him to articulate the words and focus his train of thought. . . . Julian exhibited exactly the symptoms of a torture victim brought blinking into the light, particularly in terms of disorientation, confusion, and the real struggle to assert free will through the fog of learned helplessness.

In his account of the court proceeding, Murray describes a perverse farrago of farce, travesty, and tragedy. This was railroaded injustice by any properly disinterested reckoning. Assange was confined in a glass enclosure the whole of the hearing—as he has been in all court appearances since. District Judge Vanessa Baraitser, the presiding magistrate, ruled against Assange on each of the points his lawyers raised. They requested additional time to prepare a defense, given that Belmarsh had deprived Assange of his records and restricted his meetings with attorneys. There would be no such extension. They argued that the extradition treaty between the United States and Britain does not apply because it excludes political offenses. There would be no consideration of the nature of Assange’s alleged crimes. A court in Madrid was at this time reviewing evidence that the Central Intelligence Agency, through a Spanish company called UC Global, had spied on Assange while he resided with the Ecuadorans. Since this included occasions when Assange was conferring with his attorneys, a finding of guilt would be sufficient to nullify the extradition order: Baraitser took no interest in this self-evidently significant case.

Five U.S. government officials sat at the back of the courtroom. Prosecutors, led by Queen’s Counsel James Lewis, scurried to confer with them before responding to each point the defense raised. Baraitser then ruled according to the prosecution’s preferences. Here is Murray:

At this stage it was unclear why we were sitting through this farce. The US government was dictating its instructions to Lewis, who was relaying those instructions to Baraitser, who was ruling them as her legal decision. . . . No one could sit there and believe they were in any part of a genuine legal process or that Baraitser was giving a moment’s consideration to the arguments of the defense. Her facial expressions on the few occasions she looked at the defense ranged from contempt through boredom to sarcasm. . . . It was very plain there was no genuine process of legal consideration. What we had was a naked demonstration of the power of the state, and a naked dictation of the proceedings by the Americans.

Toward the end of his report, Murray offered a few details as to Assange’s circumstances at Belmarsh. These, too, should be of interest to us:

He is kept in complete isolation 23 hours a day. He is permitted 45 minutes of exercise. If he has to be moved, they clear the corridors before he walks down them and they lock all cell doors to ensure he has no contact with any other prisoner outside the short and strictly supervised exercise period. . . .That the most gross abuse could be so open and undisguised is still a shock.

There are, indeed, gross abuses galore in the fate of Julian Assange during this time—and since, certainly. These abuses have been by turns political, physical, psychological, and at last judicial. When preliminaries ended and formal extradition hearings began last February [in 2020], Assange was again confined to an armored glass box—unable to sit with his attorneys, unable to communicate with them while witnesses were called, with no access to the defense’s court papers, with no chance to speak—a muted spectator at his own hearing.

When Assange’s defense protested his preposterous confinement in a secure dock as if he were a dangerous criminal, Baraitser asserted (yet more preposterously) that Assange would have to post bail to be released from his glass confinement and sit with his lawyers. By this time, the court had psychiatric documents diagnosing Assange with clinical depression. “I believe the Hannibal Lecter-style confinement of Assange,” Craig Murray (again present) wrote, “is a deliberate attempt to drive Julian to suicide.” There is something extreme in this conjecture, at least to the ordinarily democratic sensibility, but it is less so when considered against all that Assange could reveal—not least the grotesque and consequential fraud of Russiagate—once he is on American soil with little left to lose.

To be honest, I do not know how shocked one should be that we are able to watch as the United States and Britain abuse their power precisely to abuse Assange openly and without disguise. While there was a remarkably prevalent news blackout in the months after Assange’s arrest, British and American authorities draw no curtain over the sorts of events I describe. What are we, on the other side of the glass separating us from Assange, to make of this? Vanessa Baraitser’s ostentatious condescension toward Assange gives us a striking and suggestive detail in this connection. Prosecutors acting for the crown but conferring in plain sight with American officials, indifferent to all legal propriety, give us another. It is often said that those who detain and try Assange intend to make an example of him—a flesh-and-blood warning to others who may attempt entrance into the empires of secrecy America and its allies operate within. This is certainly so, but it is not the whole of the case. The rest of us, without ambitions to blow whistles or expose official wrongdoings, are also objects of the exercise. As Assange is disoriented, so are we to imagine ourselves. His confusion is intended to be our own. Baraitser condescends to us when she condescends to Assange and his attorneys. His struggle to assert free will is—but precisely—our struggle. In his learned helplessness—a psychiatric term coined by behaviorists to denote a coerced surrender to authority—we recognize our own. Assange’s totalized silence: again, it is to be ours. To gather these thoughts as one, we are meant to watch as the sovereign state demonstrates what the Assange case requires us to call limitless subordination. This phenomenon should not escape us.

“The arrest of Assange is scandalous in several respects,” Noam Chomsky writes in his contribution to In Defense of Julian Assange. “One of them is just the show of government power.” The linguist’s words are deceptively freighted for all their apparent simplicity. In them lies the irreducible meaning of Julian Assange’s fate. It is a question of purposeful display. What has become of power in the remnants of our democracies, the extent of its reach, what it guards at all costs, what it further aspires to, our relation to it: This is what we are meant to see.

■ ■ ■

THE ORIGINS OF TOTALITARIANISM is commonly read as a condemnation of the Nazi and Stalinist regimes, specifically as these found their most debased expression in concentration and extermination camps. This is fine but insufficient. We cannot underestimate the pertinence to our circumstances of Hannah Arendt’s tour-de-force exploration of what she termed “total domination.” It is no good taking the camps or the systems that begot them as one-off aberrations to be excised from our understanding of history. This was Arendt’s very point in giving us an account of totalitarianism that reaches back to the nineteenth century. She persuasively establishes the phenomenon as part of the modern condition, and I do not know that we have left off being modern.

Arendt runs relentlessly and deep as she defines total domination in its fulsome specificities. Its intent is to strip humanity of all identity and individuation. It is to reduce all who are subjected to it to an interchangeable “bundle of reactions,” none in the slightest different from any other. Perfect predictability leads to perfect control. Here is Arendt on the means by which this is to be accomplished:

Totalitarian domination attempts to achieve this through ideological indoctrination of the elite formations and through absolute terror in the camps. . . . The camps are meant not only to exterminate people and degrade human beings but also serve the ghastly experiment of eliminating, under scientifically controlled conditions, spontaneity itself as an expression of human behavior and of transforming the human personality into a mere thing. . . so the experiment of total domination in the concentration camps depends on sealing off the latter against the world of all others, the world of the living in general.

We will come to our indoctrinated elites shortly. For now let us remain with Arendt’s thought of absolute terror. How far must we travel from her idea to the learned helplessness Craig Murray detected when he saw Assange in the Westminster court for the first time since his incarceration at Belmarsh? How shall we understand the Assange in our three images, the Assange rendered barely articulate over his months at Belmarsh, as we watch Arendt’s acute mind at work? Certainly he has been sealed off against the world of all others. Do we witness— by glimpses, of course, our shards of pottery—a systematic effort to squeeze all spontaneity from him?

These questions are not difficult. Our replies require us merely to set aside the grim images of the camps we carry in our heads like frames in a grainy newsreel. Then, our minds clear, we must allow ourselves to think about convergences. History is our merciless but best guide. One of its bitterest lessons is the tendency of great powers to become what they stand against. The purportedly innocent are over time transformed into the guilty. The enemy of torture lapses into torture. The anti-imperial power becomes an empire. Hardly is the thought novel. It proves out almost invariably.

“What is a camp, what is its juridico-political structure?” Giorgio Agamben asks in Homo Sacer, a brief book he subtitles Sovereign Power and Bare Life. “This will lead us to regard the camp not as historical fact and an anomaly belonging to the past (even if still verifiable) but in some way as the hidden matrix of the political space in which we are still living.”

This is altogether bold on the Italian philosopher’s part. But as we shed our resistance to so startling a thought we read more clearly into what has become of Assange since his arrest. We can now recognize the purposeful extreme of his isolation—in prison but also from us, “the world of the living.” No access to a computer, to his records, to (most of the time) a telephone: What is this if not an effort to obliterate identity to the extent possible, to strip away all spontaneity—which I take to mean autonomy, agency? What do we make of a man who struggles to say his name? In his helplessness do we see the previously robust doer of deeds reduced to a bundle of reactions?

Arendt does not seem to have explored how her discoveries might bear upon us now, we the living. But it is hardly too large a leap to think of Assange’s time at Belmarsh—such as we know of it—as an experiment of the kind Arendt so well investigated. At its sordid core, there is the same effort to dismantle the personality. It is this Assange wrote of when he told Gordon Dimmack he was unbroken but surrounded by murderers—murderers of the spirit as well as those around him charged with homicide, in my reading of his letter. From the first of the photographs considered earlier to the person Craig Murray saw standing before Judge Baraitser six months later, we have a record of his tragic regress toward the condition of “mere thing.” Borrowing from a scholar named Jon Pahl, let us call this innocent domination—the dominating power’s claim to virtue in its act of domination.

The third and final part of this essay will appear shortly.