“Saints and sinners.”

Heresthetics as political art.

This is the first of a two-part series.

Structuring the world so you can win. This sounds like sorcery, but in politics there is a phenomenon known among the social scientists as heresthetics, and it has been with us for centuries. It paved the way for an Illinois senator named Abraham Lincoln to achieve the presidency. Closer to our time, oligarchs deploy the techniques of heresthetics as they seek to strangle the United States Postal Service. Militant libertarians, not to be left out, use it to cripple the very machinery of the United States government.

This art, black or otherwise, can have profound ramifications when wielded effectively. Let us understand this phenom called heresthetics: It has a lot to do with the way America’s political life proceeds.

The term was coined by William H. Riker (1920–1993), the American political scientist who founded the field of Positive Political Theory. PPT, you will be delighted to know if you do not already, is the study of politics through the lens of game theory and statistical analysis. Game theory and its cousin, rational choice theory, are particular favorites around The Scrum’s offices: We love their essentially dehumanizing, monumentally flawed assumptions and all the appalling mistakes they have led our nation to commit over the decades since the celebrated John von Neumann co-wrote (with Oskar Morgenstern) his Theory of Games and Economic Behavior in 1944.

Riker considered heresthetics, at its theoretical core, to be the fourth liberal art, alongside the medieval arts of logic, grammar, and rhetoric. As he put it, the theory of heresthetics is “concerned with the strategy value of sentences.” In practical application, heresthetics has been employed in the past by political figures such as Lincoln (as he destroyed Illinois Senator Stephen Douglas’ presidential aspirations in 1858) and in the present by hack pols such as West Virginia Senator Joe Manchin (as he refuses to overturn the Senate filibuster). Shrewd or something closer to diabolic, the record leaves little room to question the rhetorical strategy’s effectiveness.

Riker documents 12 practical heresthetical examples in The Art of Political Manipulation, which Yale brought out in 1986. Let us explore some of his examples and consider Riker’s three general categories of heresthetical tactics: agenda control, strategic voting, and manipulating dimensions. Two contemporary examples are worth special note as they fall under the third and most commonly used heresthetical category, that of manipulating dimensions.

Agenda control. This first heresthetical category, whereby the formal leadership of a decision-making body attempts to shape the list of things to be considered in such a way that aims congruent with the wishes of the leadership are fulfilled while alternatives contrary to the wishes of the leadership are defeated. Riker, in Chapter12 of Manipulation, uses a case that dates to 1890, when House Speaker Thomas B. Reed redefined a quorum, as a perfect illustration of the heresthetic tactic of agenda control.

Prior to Reed’s election as speaker in 1889, the House’s Republican majority was unable to enact any legislation due to an opposition tactic known as the disappearing quorum. This involved the minority Democrats taking advantage of a legal loophole that allowed them to withhold their votes if the margin between majority and minority was less than the number of physically absent members.

Since the Republican majority at the time could rarely produce the minimum numbers needed for a quorum due to reasons such as illness or travel, and the resulting gap between majority and minority was less than the number of absentees, the minority party could bring business to a halt simply by withholding the votes of its members, so denying Republicans their needed quorum. It was a kind of faux-absenteeism.

In January 1890, the Democratic minority attempted the disappearing quorum tactic yet again, but Speaker Reed was this time prepared to overcome his enemy. In a theatrical display, Reed began reading aloud the names of the 165 Democratic members who were present and yet withholding their votes. This enraged the Democrats, who vehemently insisted that they were not actually present by their interpretation of the disappearing quorum loophole. It was at this point that Reed sprung his logical trap upon his enemies.

As Reed put it:

There is a provision in the Constitution which declares that the House may establish rules for compelling attendance of members. If members can be present and refuse to exercise their function, to wit, not to be counted as a quorum, that provision would seem to be entirely nugatory. Inasmuch as the Constitution only provides for their attendance, that attendance is enough. If more were needed, the Constitution would have provided more…. The Chair therefore rules that there is a quorum present within the meaning of the Constitution.

A few days later, the House adopted Reed’s quorum reform, due to his interpretation of the Constitution and his theatrics gaining the support of Republican members. By leveraging his leadership role as Speaker, Reed was able to rally his fellow Republicans and seize control of the political agenda in the lower chamber.

This is agenda control in a fairly pure form. It is a technique that continues to be practiced in American politics. One need look no further than the case of the disappearing Democrats in Texas, which I will revisit shortly. Or the case of the Parliamentarian of the Senate, Elizabeth MacDonough, selectively citing the Byrd Rule to block a proposed minimum wage increase as part of a Covid–19 relief bill in February 2021.

Strategic voting. In this second heresthetical category, Riker turns the tables. By resorting to strategic voting, individual members of a governing body, as opposed to the leadership (who act according to the agenda control concept), can advance or halt an agenda by strategic use of their voting power. Riker devotes Chapter 9 of Manipulation to a prominent example of strategic voting, the 1980 defeat of the Equal Rights Amendment in the Virginia Senate.

The Equal Rights Amendment is a proposed amendment to the Constitution that guarantees equal legal rights to all citizens no matter their sex. As with all amendments, Article V of the Constitution requires a minimum of 38 state ratifications of the ERA; in 1980, the number of state ratifications was up to 35, not counting legally questionable revocations.

For its part, Virginia requires an absolute majority in the State Senate for the passage of a resolution to ratify an amendment to the Constitution, and in 1980 the Senate was tied 20 to 20 on the ERA vote. Were this tie to have persisted, the lieutenant governor would have been allowed to cast the tiebreaker vote (and would have done so in favor of the ERA).

However, due to the actions of State Senator John Chichester, this was not to be. In a clever move, Chichester used a Senate rule that allowed a member to abstain from voting on an issue in which he or she had “an immediate, private, or personal interest.” The Senate leadership did not contest this interpretation of the Senate rule, and Chichester won out. When he claimed such an interest and withheld his vote, it meant there was no tie to break, the vote in favor of the ERA could not result in an absolute majority, and the resolution was defeated.

This strategic withholding of a single vote by a person not in a leadership role was nonetheless able to delay the ratification of the ERA in the Virginia Senate until January of 2020. Just as agenda control is exercised in the present day, so, too, is strategic voting. In a famous case that made page one news around the country, Texas House Democrats left the state in an effort to deny Texas House Republicans a quorum, thwarting the passage of voting restrictions that will benefit Republicans.

Manipulation of dimensions. According to Riker, this third heresthetic category is defined as “raising against a disputed alternative still another dimension of judgment that splits the opposition,” or “when the currently winning side anticipates that the opposition will add a dimension to split the winners” and blocks the added dimension.

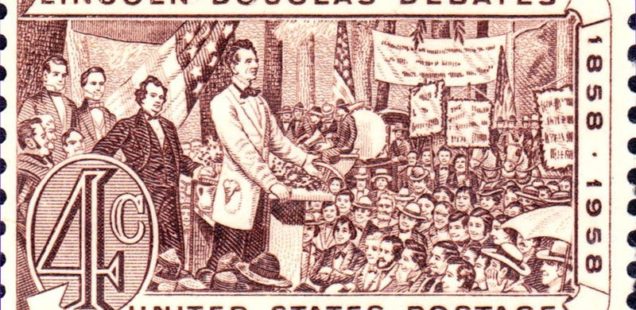

Riker’s first chapter is an account of one such dimensional manipulation by Honest Abe, who proved a master heresthetician. In 1858, Lincoln the Republican was campaigning for the Illinois Senate seat of incumbent Democrat Stephen Douglas. As is well-known, Lincoln and Douglas participated in a series of seven debates. In the second, at the town of Freeport, Lincoln put Douglas in a heresthetical trap by adding a dimension to the debate.

Lincoln posed the following question to Douglas:

Can the people of a United States Territory, in any lawful way, against the wish of any citizen of the United States, exclude slavery from its limits prior to the formation of a state constitution?

How very quick of Lincoln. As he must have understood perfectly well, this was a trap because Douglas needed antislavery Northern Democratic votes to maintain his Senate seat but needed proslavery Southern Democratic votes for a presidential run in 1860. If Douglas answered yes to Lincoln’s question, this would satisfy the Illinois Democrats but would anger Southern Democrats. On the other hand, answering no to Lincoln’s question would jeopardize his chance to maintain his Senate seat but would satisfy the proslavery Southern faction of the Democrats he needed to secure the party’s presidential nomination in 1860.

Douglas answered yes to Lincoln, won reëlection to the Senate—and ruined his chances to win a presidential run in 1860. Lincoln may have lost the short-term battle but he won the long-term war, as he went on to his history-altering victory in the presidential election in 1860.

Of the three of the heresthetical categories just reviewed, Riker had this to say:

Often it is difficult to control the agenda or to vote strategically, especially if the equilibrium winner has a substantial majority. But the number of dimensions can always be used to upset an equilibrium, provided the heresthetician is clever enough to find the correct dimension to use. This, no doubt, is why manipulation of dimensions is just about the most frequently attempted heresthetical device, one that politicians engage in a very large amount of the time.

A plague of privatizers.

There is more than historical curiosity or scholarly pedantry attaching to the heresthetical phenom. With Riker’s thesis in hand, we have two contemporary examples of dimensional manipulation to think about, neither of which offer us much in the way of edification: the financial straitjacketing of the United States Post Office to force its eventual failure and possible privatization, and the push to adopt a Balanced Budget Amendment to prevent Keynesian intervention in U.S. markets.

The USPS is one of the few government agencies explicitly authorized by the Constitution. According to the Postal Clause, Congress has the authority “to establish Post Offices and Post Roads.” This explicit constitutional authorization has made the Post Office very robust against attacks from corporate interests and libertarian ideologues. In 2006, however, a clever implementation of the heresthetical “limiting of dimensions” tactic breached the defenses of the USPS and now threatens its very existence as a public entity.

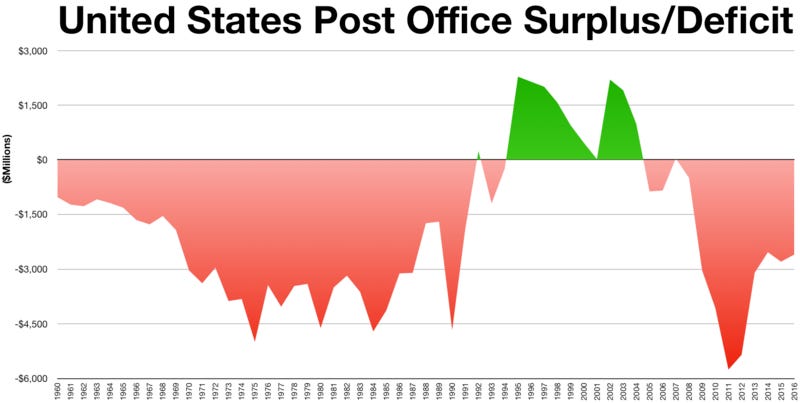

In 2006, H.R. 6407 (109th): Postal Accountability and Enhancement Act was signed into law. This law requires the USPS to prefund its retirees’ health benefits up to the year 2056, a preposterous requirement that does not exist anywhere else in the public or private sectors. Additionally, the law restricts the ability of the USPS to raise funds via nonpostal services such as banking and limits the ability of the USPS to raise postal rates beyond the rate of inflation. This law has been a very clever effective limitation of the fiscal dimension, as it has forced the USPS into losses totaling billions of dollars without no relief in sight.

Now you know how it is done. Now you know how a pillar of our public sector and our public space altogether has been brought to its knees. This is what we mean by “diabolic.”

Another 21st century example of dimensional manipulation is the attempt by corporate and libertarian ideologues to add a Balanced Budget Amendment to the Constitution, thereby limiting the fiscal dimension. Just as the limitation of the fiscal dimension is driving the USPS to inoperability, the implementation of the BBA would restrict the use of Keynesian deficit spending, so imperiling the funding of public goods and countercyclical spending during an economic downturn.

The BBA movement was born after the breakdown of the Keynesian consensus during the 1970s. One of the prime movers in the BBA movement, libertarian James M. Buchanan, wrote an entire book, Democracy in Deficit, published by Academic Press in 1977, dedicated to savaging Keynesian economics. Buchanan’s criticisms in this book culminate in a call for a Balanced Budget Amendment, and he gives an outline for such a proposal.

In 1980, a push for a convention to propose a BBA narrowly missed the required 34–state benchmark needed to trigger a Constitutional convention. The next closest attempt to impose the BBA was in 1995, during the time of Newt Gingrich’s Contract with America campaign. The BBA proposal passed the House of Representatives but was narrowly defeated in the Senate.

Since that time, BBA supporters have continued their campaign. As of now, there are 28 states calling for adoption of a BBA. If implemented, this would be a dimension-limiting equivalent of a nuclear bomb, the USPS situation writ large. In addition, the Constitutional convention triggered when the 34–state minimum was met would not be limited to the topic of the BBA, so there would be ample opportunities for other Constitutional alterations. If alterations in addition to the BBA were to come to pass, the push for a BBA could result in a horrifying, heresthetical masterpiece.

Once one views past and current politics through a heresthetical lens, one realizes how abundant application of the fourth liberal art is and how consequential its application can be. Perhaps the above-cited examples drawn from Riker, as well as the contemporary cases just mentioned, will convince readers of how consequential cold, hard applications of heresthetical techniques can be. The term may be obscure to the general public. As Riker discovered, its potency is not.

There is one other contemporary heresthetical example that merits exploration in its own essay: the manipulation of dimensions via cancellations, shadow banning, and algorithmic manipulation in the 21st century equivalent of the town square: social media.