PATRICK LAWRENCE: In Venezuela, US Forgets What Century It Is

Destabilizing other nations in gross violation of international law will no longer go unopposed, writes Patrick Lawrence.

The Venezuela crisis worsens by the day. Early last week the U.S. sanctioned PdVSA, the state-owned oil company, by sequestering income from U.S. sales in a blocked bank account. On Sunday President Donald Trump confirmed in a television interview that deploying American troops is “an option.”

Little of what Washington has done in the weeks since it recognized an opposition legislator, Juan Guaidó, as Venezuela’s “interim president” has any basis in international law. But there is much worse to come and much more at risk if the U.S. follows through with its recently disclosed plans to reshape Latin American politics to its neoliberal liking.

Administration officials now advertise the effort to depose the government of Nicolás Maduro as merely the first step in a plan to reassert American influence among our southerly neighbors. The next two targets, Cuba and Nicaragua, are what John Bolton, Trump’s national security adviser, calls the continent’s “troika of tyranny.”

“The United States looks forward to watching each corner of the triangle fall—in Havana, in Caracas, in Managua,” Bolton said in a not-much-noted speech in Miami late last year. “The troika will crumble.” There is cold comfort to derive from knowing this forecast reflects the single most deranged worldview of anyone now active in the Trump White House.

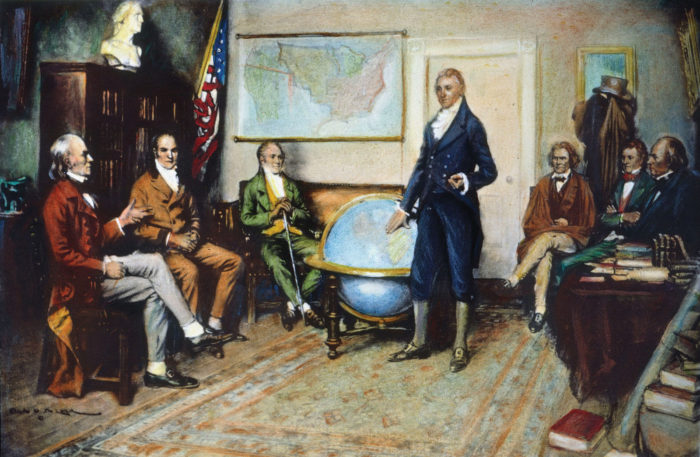

“The Birth of the Monroe Doctrine” by Clyde O. DeLand: U.S. President James Monroe presides over a cabinet meeting in 1823, discussing the Monroe Doctrine. (Wikimedia)

But therein lie considerable dangers. In effect, Trump and his policy minders intend to revive the Monroe Doctrine, in which the fifth U.S. president effectively declared the Western Hemisphere America’s to manage however it wished. But it is 2019, not 1823, when James Monroe made his case in a State of the Union speech to Congress. It is frequently remarkable how blind Washington is to the limits the 21stcentury imposes on its power, and we are about to watch it crash into two of them.

Era of Coups Is Over

For one thing, the long era of U.S.-cultivated coups— “regime changes” for those who cannot quite face this aspect of America’s conduct abroad—is over. First in Ukraine and a year later in Syria, Moscow has put Washington on notice: Destabilizing other nations in gross violation of international law will no longer go unopposed. One way or another, this will again prove true in Venezuela.

The Ukraine case ranks among the worst foreign policy calls former President Barack Obama made during his eight years in office, and there are many from which to choose. State Department-sponsored NGOs and “civil society” groups such as the National Endowment for Democracy had been up to their customary chicanery in Kiev for years before Obama took office. But it was Obama who green-lighted the operation that led, five years ago this month, to the ouster of Viktor Yanukovych as Ukraine’s duly elected president and the division of the country into pro–Western and pro–Russian halves that remain at war with one another.

It is now de rigueur in the Western press to date the Ukraine crisis—and the sanctions regime that remains in place—to Russia’s re-annexation of Crimea after a referendum held in March 2014. This is ahistorical nonsense. It is a matter of record that Vladimir Putin convened his national security advisers the night of Feb. 22, a day after Yanukovych was forced to flee Kiev. By dawn on the 23rd, the Russian president had decided there was no alternative to reclaiming Crimea if Russia was to prevent NATO from assuming control over its only warm-water naval base.

A middling graduate student in international relations could have told the State Department’s Victoria Nuland and Vice President Joe Biden, who carried the administration’s Ukraine portfolio, that precipitating a coup in Kiev was a reckless, amateurish business. And so it has proven.

President of Syria Bashar Assad made a working visit to Moscow on Oct. 20, 2015. (The Russian President)

In the Syrian case, the U.S. had been training, arming, and financing radical Sunni jihadists since 2012 at the latest. But it was only in September 2015, a year after the Ukraine debacle, that Moscow—at the invitation of the Assad government in Damascus—entered the conflict militarily. The result speaks for itself: The Syrian Arab Army is now finishing its mop-up phase and the European powers, along with Turkey and Russia, are negotiating a variety of political, social, and economic reconstruction plans.

It is stunning, in the context of these two events, that the U.S. now proposes to embark on a series of three coup operations in Latin America, the first of which unfolds as we speak. But learning from past errors has never been among Washington’s strong suits, to put the point too mildly. The Maduro government warns the U.S. of “another Vietnam” if it intervenes militarily in Venezuela. Moscow warnsof “catastrophic consequences.”

Let us not misread this last remark. It is highly unlikely, if not unimaginable, that Russia would counter direct U.S. intervention in Venezuela through military support. Moscow has all but said as much, indeed.

Russian and Chinese Interests

But we now come to the second limitation on American power in the 21stcentury. In an era of virtually unlimited economic interdependence, Russia and China have considerable interests in Venezuela, and you can bet your last ruble or renminbi that they will exert themselves to protect them.

China has developed a series of oil-for-loans agreements with Venezuela over the past dozen years, and these total more than $50 billion in value. At this point Caracas is some $20 billion in arrears on these deals, according to official Chinese sources as quoted in The Wall Street Journal. Russia has also invested many billions in Venezuela since the years of the Hugo Chávez presidency. Logically enough, both Moscow and Beijing question whether a post–Maduro government would honor these obligations.

PDVSA building 2008. “Fatherland, socialism or death.” (Nicolas Hall via Wikimedia)

China and Russia are also Venezuela’s largest arms suppliers, and both have intelligence-gathering installations on Venezuelan soil. Two days after Washington recognized Juan Guaidó as Venezuela’s interim leader, reports surfaced that Moscow had dispatched a team of private contractors—read: mercenaries—to support the Maduro government.

The Atlantic Council, a Washington think tank known for its anti–Russian biases and its close ties to various intelligence agencies, put out a paper over the weekend suggesting that the Venezuela crisis marks the beginning of “great-power competition” in Latin America. For once, the council seems to have gotten it roughly right.

No, this is not likely to resemble the Cold War in its superficial aspects. While Washington appears likely to fight it with hunger-inducing sanctions, semi-covert subterfuge, and possibly armed interventions, Russia and China will rely on diplomatic and possibly military support, economic aid, and investment. Both Moscow and Beijing continue to back the Maduro government and have encouraged political negotiations between the Venezuelan president and his adversaries.

The best way to read this competition at the moment is to recall the years prior to the Obama administration’s diplomatic recognition of Cuba (which the Trump administration has all but officially dismantled). Obama was more or less forced to act, because decades of merciless economic embargo and non-recognition had thoroughly alienated the rest of Latin America. Depending on how events turn in Venezuela, Trump and his policy minders could easily land Washington back in the same unenviable predicament.

Thank you for this piece. I have paid more attention to Latin America than to Ukraine and Syria, so I especially appreciate your brief summary that places these two countries within the global pattern of regime-change attempts. My only quibble with this commentary is that you imply that the US will try regime change in Nicaragua if it succeeds in Venezuela. The US already *did* try regime change in Nicaragua, in collusion with various elites and “civil society” organizations long supported by NED – in April – July 2018. The debate about Nicaragua continues, but mostly at the international level. Most people in Nicaragua got a pretty good taste of what the opposition was capable of, and they’re not interested. Not to say that the US might not try again. One difference between Venezuela and Nicaragua is that much of Nicaragua’s economy is in the small-business and social sectors, which makes it a bit more robust and resistant to economic sanctions.